10 Apr Problem Management:

A Behavioral Science Approach

by Ralph H. Kilmann

This article was originally published in G. Zaltman (Ed.), Management Principles for Nonprofit Agencies and Organizations (New York: American Management Association, 1979), pages 213-255.

INTRODUCTION

Managers are continually beset with problems. Some of these are very well structured, concrete, easily definable, and solvable. For example, which of three photocopiers is most economical to purchase or lease given the projected duplicating needs of the high school? Which of two candidates would best fit the job of assistant to the hospital administrator? Which of three methods of inventory control would minimize out-of-stock inconveniences with regard to the welfare agency’s reporting forms? Other problems are very ill structured, vague, and difficult to define, and it is not often known if lasting solutions can be found, since the nature of the problem keeps changing. For example, should the university’s goals be altered? How should civil service employees be effectively motivated? What new charitable programs should the organization formulate and implement? Which new medical science technologies can and should be developed?

One might even define the essence of management as problem defining and problem solving, whether the problems are well structured, ill structured, technical, human, or even environmental. Managers of organizations would then be viewed as problem managers, regardless of the types of products and services they help their organizations provide. It should be noted that managers have often been considered as generic decision makers rather than as problem solvers or problem managers. Perhaps decision-making is more akin to solving well-structured problems where the nature of the problem is so obvious—that one can already begin the process of deciding among clear-cut alternatives. However, decisions cannot be made effectively if the problem is not yet defined and if it is not at all clear what the alternatives are, can, or should be.

THE NEED FOR PROBLEM MANAGEMENT

It has become apparent to most management scholars and practitioners that contemporary organizations are facing increasingly dynamic and changing environments. This poses more complex and ill-defined problems than organizations have previously had to address. (Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock presents an excellent discussion on the pervasiveness of such changes and how this fosters complex problems.) Further, complex problems often involve the entire organization, not just one or two departments or one or two individuals. These problems can never be completely resolved, since they are always present (for example, relevance of organizational goals to changing societal needs). This suggests that the shift of the manager from decision maker to problem definer and solver (that is, problem manager) is quite appropriate.

Organizations, however, are designed for performing specific, day-to-day activities and for providing well-defined products and services—not for addressing complex and changing problems. In particular, organizations have operational subunits (medical specializations as in hospitals, teaching programs as in schools and universities, social programs as in government agencies) to pursue fairly well-defined goals and tasks. But how can the organization engage in effective problem management if it is primarily designed for day-to-day concerns and if complex and changing problems do not fit well into the design categories or boxes on the organization’s chart? Also, what if people in the organization are trained and expected to spend most or all of their time managing daily matters in their specific departments and not ill-defined and fuzzy matters that cut across department lines? What if routine matters and goals of “productivity” drive out planning and creativity? Perhaps effective problem management is becoming a much needed function for organizations. Perhaps available knowledge about individual and organizational behavior should be applied to suggest how effective problem management can be designed and conducted (see Kilmann, 1977).

While the above arguments are as relevant to profit as well as nonprofit organizations, the latter seem to require more explicit problem management. Briefly, profit-based organizations have available a number of yardsticks for decision making and problem solving, which nonprofit organizations do not. And even though profit-based, economic decision models are often far removed from the real-world conditions of uncertainty and incomplete information, they nevertheless provide some guides for decisions and actions (see Downs, 1966). Some simple problems for profit organizations (decision making) become more ill defined when these same types of problems are considered for nonprofit organizations. For example, a rather straightforward cost-benefit analysis for developing a new product in a particular market for a profit organization becomes broadened to include political, geographical, and legal “fuzzy” issues when a nonprofit organization considers expanding its services.

This chapter seeks to provide a comprehensive discussion on problem management especially suited for nonprofit organizations. Questions to be explored include: Who should be selected to engage in problem management? What should the criteria of selection be? What type of special logic or thought process is especially suited to defining problems? How should individuals be composed into groups in order to partake in problem management effectively? How does one assess effectiveness in problem management? How should individuals interact with one another so that problems are defined and solved properly? How should individuals resolve their differences if they disagree on the nature of the problem? Are there certain basic steps to go through to assure that problems will be managed effectively? What errors can take place at each step?

Because all these questions demonstrate just how complicated problem management is, a special effort is made to organize the discussions into frameworks and diagrams that will help in sorting the material into meaningful, related subparts. This chapter first presents a definition and discussion of the five generic steps of problem management. Included is a discussion of what constitutes effective problem management and the types of errors that need to be either avoided or minimized at each step. The processes are then distinguished from the structures involved in problem management and attention is directed to whether these processes and structures take place and exist within individuals or between individuals (as in group interactions). These distinctions form four very different but equally important action areas of problem management—that is, areas for acting upon and addressing the types of questions noted above. The four action areas are explored separately, with suggested principles and guidelines for ensuring that each is identified and conducted appropriately. Finally, the chapter presents the Problem Management Wheel, an integrated diagram portraying not only the four separate action areas and the five generic steps of problem management, but also how these need to be linked together in order to foster overall effectiveness.

THE GENERIC STEPS OF PROBLEM MANAGEMENT

Most people in organizations experience and act upon problems, either implicitly or explicitly. Sometimes managers (for example, school administrators) bring in outside consultants (curriculum specialists) to help them solve organizational problems. While managers or consultants may differ in how they approach problems, one can define certain ideal or typical steps that should or can be conducted whenever the issues emerge as to what is wrong and what can be done about it. In fact, it can be argued that styles of problem management differ according to how the ideal or typical steps are conducted as well as whether certain steps are emphasized and others ignored.

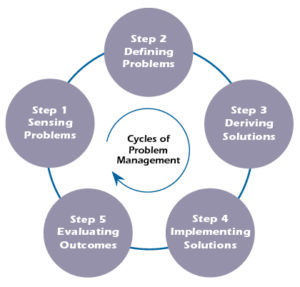

Figure 1 shows the five general steps of problem-defining and problem solving processes: sensing the problem, defining the problem, deriving solutions to the problem, implementing particular solutions, and evaluating the outcomes of the implemented solutions. The cycle then repeats by noting whether a problem is still sensed. Certainly, one could fist other decisions or action steps in this process (for example, choosing various strategies for implementing solutions or choosing approaches for evaluating outcomes), but these could be incorporated into the key five steps.

Figure 1

The Five Generic Steps of Problem Management

Step 1: Sensing the Problem

One would logically expect the process to start at a point where one or more individuals in the organization sense that something is wrong or that some problem exists. A problem is here defined as a discrepancy between what is (current performance) and what could or should be (expected performance or organizational goals). Once the gap between what is and what should be goes beyond some threshold, a problem is perceived. For example, the turnover rate in a museum may be 15 percent per year, which may be expected, given the nature of the labor force and the general mobility expected. However, if the turnover rate became as high as 40 percent, individuals may well perceive some problems, since this rate significantly exceeds their expectations or threshold levels. This type of sensing or experiencing has been referred to as the “felt need for change.”

Any number of indicators, both formal and informal, can be used to assess whether a problem exists: increased cost of providing services, smaller appropriation of resources, decrease in clientele, competing agencies providing the same services, change in public image of organization, low morale, turnover, absenteeism, increase in complaints, and general anxiety or frustration on the part of civil service members. Once any or several of these indicators break some threshold of tolerance, individuals in the organization usually perceive that problems exist.

An exception to this might be when goals, aspirations, and expectations are so low that everything seems fine even though the organization is slowly decaying. Here the organization’s perceptions may be out of line with reality. The organization may be denying its problems or may be afraid to confront problems because it perceives itself as ineffective. All these possibilities for denying the existence of a problem (or not recognizing a problem) are referred to as a Type 0 error: the probability that a problem exists but is not sensed. For example, any complex government agency that claims that it does not have any problems is probably stating its problems without realizing it and is committing a Type 0 error. Likewise, a large school system without problems simply does not exist. The question is: What is the most important problem to address, given the resources of the organization?

Step 2: Defining the Problem

Once it is sensed that a problem exists, step 2 is to define just what the problem is. For example, is the museum’s high turnover the result of interpersonal conflict, low job satisfaction, few promotion opportunities, competitive job offers from other organizations, a change in the nature of the job market, a basic problem in job description, or outdated organizational tasks? Any or several of these possible problem definitions could be the reason behind the high turnover rate. Specifically, the problem is viewed as the cause for an indicator breaking the threshold. The object of this step, therefore, is to work backward from the perceived difficulty to try to determine or suggest what really caused it.

Problem definition is probably the least understood step in the whole process, because it is the most ill structured. How does one know when a problem is defined properly? What are the alternative definitions to a problem situation (as distinguished from solutions), and how can these alternative definitions be generated? How should alternative problem definitions be evaluated and a single or integrated (synthesized) definition be chosen?

Because problem definition is so ill structured and often subjective, it is not surprising that problem managers as well as consultants often bypass this part of the process. They simply assume that they know what the problem is. In particular, it appears that each external consultant or internal manager applies his approach to the problems of the organization without carefully considering whether that approach is indeed suited for the organization’s particular problem. Of course, most individuals assert that it would be inappropriate and even unethical to use approaches, including their own, if these were not germane to the organization (that is, if they would not solve the organization’s problems). But one must consider whether the problem manager can really be objective in such a decision. This is especially the case if, like most professionals, he is trained in one or at most two specialties and therefore cannot assess whether other approaches would really be better suited to the problem at hand.

It is natural, for example, to expect that a human resource manager or consultant trained in interpersonal relationships and group dynamics would perceive that the inefficiencies in the organization are caused by less than adequate interpersonal relationships and group processes; that a manager specializing in marketing would view the same situation as being caused by ineffective advertising campaigns; and that an industrial engineer would see the identical situation as stemming from man-machine interface problems or the inefficient flow of work materials. The same “selective perception” and biases could also be expected from managers specializing in management, accounting and finance, management information systems, and so on.

While the major error of problem sensing is denying the existence of a problem and assuming that everything is fine (Type 0 error), the major error of problem definition is formally referred to as the Type III error: the probability of solving the wrong problem instead of the right problem (Mitroff and Featheringharn, 1974) or solving the trivial problem rather than the most important problem given the resources and needs of the organization. But how do managers of the organization define what the basic problem is that is causing the various perceptions? More often than not, as has been suggested; individuals assume that their view of the world (their specialty) defines the essence of the problem. Alternatively, some top manager or person “close to the problem” defines what it is and all attention, including the time and energy of other managers and consultants, is devoted to solving that definition of the problem. And when one asks, “Why are you implementing that particular solution or approach?” the response is, “Because such and such is the problem.” “And why is that the problem?” The response follows, “Because the director says it is so.”

One might wonder if such implicit problem definitions do not typically result in significant Type III errors—solving the wrong problem. Experience has shown that a particular definition of the problem is addressed because that is the way it was always done, even if the existence or sensing of the problem never disappears or gets resolved. An example is the hospital administrator who defines the problem of needing better doctors when the real problem is that the existing doctors (or even new doctors) cannot communicate across their medical specialties to address complex patient ills.

Step 3: Deriving and Selecting Solutions

Step 3 in the process concerns the derivation of solutions to the already defined problem and the selection of a single solution. Most discussions on decision theory, management decision making, and even statistical decision analysis concentrate on this aspect of the process. One can usually construct a “decision tree” indicating the alternatives that are available in the situation (as branches of the tree), with associated costs and probabilities of leading to the desired outcome (generally with respect to optimality). Sometimes, alternate action steps follow beyond each main alternative resulting in branches leading off from other branches. Then, a cost-benefit analysis or a calculation of the expected net value for each alternative enables the decision maker (problem manager) to choose a single solution to the previously defined problem. (Because this part of the process is well documented in other literatures, further details are not presented here. (See, for example, Schlaifer, 1959.)

Two related errors have been discussed extensively with respect to choosing between two well-defined alternatives in statistics, which can be generalized to choosing among several alternative solutions to a problem. Type I and Type II errors are the probability of not rejecting alternative A when B is in fact “true” or the best, and the probability of accepting alternative B when A is in fact “true” or best, respectively. These two errors, of course, assume the relevance, importance, and rightness of the problem definition for which the alternative solutions are desired. But if a Type III error has been committed (defining the problem incorrectly), spending time on Type I and Type II errors is meaningless and irrelevant. Type I and Type II errors concern the appropriate choice among the branches of a given decision tree, while Type III errors concern whether the right decision tree was chosen when compared with alternative whole decision trees.

Perhaps an anecdote (modified from Ackoff, 1960) would help to distinguish these important errors relative to problem definition and alterative solutions. This story takes place in a large university building where the administrator began receiving more and more complaints from students concerning the long time spent waiting for elevators. Sensing there was a problem (from the many complaints), he consulted his engineering staff for a solution. Naturally, the staff defined the problem implicitly as a technical one. In fact, it seemed as though the problem definition was not even an issue; it was simply assumed. The engineers suggested two alternatives for a decision tree: speed up the existing elevators or install new elevators. Both alternatives incurred a very high cost.

As the administrator was weighing these alternatives, he shared the problem with another person on his staff who had a background in psychology. This person suggested that the problem was a human one—that the perception of time is subjective and perhaps the students complain because they cannot do anything else while time passes waiting for the elevators. Defining the problem in these terms suggested two alternatives: place mirrors in the hallways at the elevator entrance on each floor, or place display cases there containing interesting and informative materials or news items. These alternative solutions were much cheaper than the first two, and actually solved the problem when implemented (there were fewer complaints).

This anecdote illustrates how a different problem definition (human versus technical) not only addresses the problem situation quite differently but does so with entirely different solution alternatives. Choosing the psychological type of definition versus the engineering type of definition is an example of a Type III error (in choosing a whole decision tree). Once a given definition is chosen, the choice of alternative solutions is an example of Type I and Type II errors (in choosing a branch of the given decision tree). While the rightness or wrongness of the problem definition in this anecdote may come down primarily to money considerations, in other problem solutions the issues might include morale, public image, ease of implementation, and other intangible yet real consequences of alternative problem definitions.

Step 4: Implementing Solutions

Step 4 in the process concerns the implementation of the chosen solution. It is one thing to derive what appears to be the optimal or best solution and quite another to implement it effectively in the organization. One can usually cite many examples of excellent solutions that were implemented poorly, not at all, at the wrong time, by the wrong people, or simply in the wrong way. Implementation should not be taken for granted—one should not assume that a good solution will automatically be accepted and find its way into the mainstream of organizational activity. There is resistance to change in any organization—members may perceive costs and psychological losses as outweighing the benefits of the proposed change. In addition to the technical and purely economic aspects of implementing solutions, therefore, there are psychological and social aspects. The latter are often a more powerful deterrent to successful implementation than the former.

The literature on organizational innovation has provided a view of the innovation process that is quite analogous to an organization adopting or implementing something new or some newly derived solution to a problem. A number of factors have been specified as affecting the likelihood that a given innovation or solution will be accepted and utilized by the members of the organization. Specifically, the model includes the following factors as perceived by organizational members: (1) the new or target level of performance of the organization (or subset of the organization considering the chosen solution), (2) the organization’s current level of performance, (3) the costs associated with adopting the solution, (4) the rewards associated with adopting the solution, (5) the probability that adoption of the solution will lead to achievement of the target level of performance, and (6) the probability that the target level can be achieved without the adoption of the solution (Slevin, 1973; Schultz and Slevin, 1975). The target level or level of performance can be generalized to any indicator wherein the organization first sensed a problem, defined it, and then chose a particular solution. This solution is intended to bring the current level of the indicator up to the desired target level.

Various combinations or comparisons of the above factors can highlight different types of constraining forces acting on implementation. Comparing the target level of performance with the current level indicates the aspirations of organizational members for improving the organization. The perceived costs relative to the perceived rewards of implementing the solution are an important indicator of the incentives operating in the situation (for example, incentives that motivate or de-motivate member acceptance). Also, differences in the probabilities of achieving the target level of performance with or without the adoption of the solution suggest members’ expectations concerning the possible impact of the implemented solution.

These concerns and issues suggest the many ways in which the implementation step can fail to achieve expected results. Basically, the members of the organization, for many reasons, may not accept the implemented solution, resist it, modify it, or even sabotage it. Not planning for implementation and not anticipating obstacles, resistances, and forces operating) keep things the same results in the Type IV error: the probability of not implementing a solution properly (Slevin, 1973: Schultz and Slevin, 1975). No matter how well the other steps in the process have been conducted and to what extent the other errors have been minimized (Type I, II, and III errors), committing a significant Type IV error can nullify the total effort at effective problem management.

To use the example of the elevator problem discussed earlier, a Type IV error would occur if the administrator had selected the solution of installing mirrors at each floor, but the mirrors that were installed were aesthetically unappealing to waiting students, or if the mirrors were too small or were not located in convenient places near the elevators, or if the halls were too dark to make appropriate use of the mirrors. Certainly, the assumption behind installing the mirrors and managing the Type III error was that the mirrors would be used while students waited for the elevators. Ignoring the logistics and psychological factors that affect the use of the solution results in a Type IV error. Alternatively, even if the solution of installing more elevators were chosen, the new elevators would have to be regarded as safe, pleasant, and efficient. Otherwise, the students might prefer to wait for the old elevators—which demonstrates a Type IV error on top of a Type III error.

Step 5: Evaluating Outcomes

The final step in the process shown in Figure 1 is evaluating the outcomes resulting from the implemented solution. Step 5 thus asks if the implemented solution actually solved the initially sensed problem. If the indicators focused on previously are no longer beyond the threshold levels, the organization may assume that the problem has been managed properly—if it is sure that it is not committing a Type 0 error. It is possible, however, for the problem to “go away” by itself, without any effort from the organization. In either case, the organization does not need to be concerned about the problem further (at least at this time). But solving the initial problem may lead to the creation or perception of other problems, and these newly identified problems may motivate the organization to continue the cycle.

If the initial problem is still sensed after the organization has gone through all five steps, it is likely that one of the steps was done incorrectly or that one or a combination of Type I, II, III, or IV errors was committed. The evaluation step is critical in attempting to pinpoint which error or errors were made prior to going through the process again in order to manage the initial problem effectively. This assumes, of course, that the evaluation step is conducted correctly in the sense of accurately measuring the “performance” and outcome of each preceding step. Perhaps a Type V error can be defined as the probability of evaluating the problem management process incorrectly. Recent research on program evaluation is seeking to minimize this error (Weiss, 1972), but for now we will assume that the organization can conduct this step appropriately.

If the initial problem is still sensed, was the problem defined correctly? Because the Type III error is the most pervasive of all the errors, this question should be asked first. Subsequent discussions in this chapter will consider the ways in which the Type III error can be minimized. This can be done by the explicit use of multiple problem definitions developed by diverse representation throughout the organization. Also helpful is the use of various individual, group, and intergroup processes in order to first debate and then synthesize these multiple perspectives. Type I and II errors, although important, are not as critical as Type III. However, the cost-benefit analysis can be rechecked to see if the wrong solution was chosen. Perhaps efforts should also be directed to discovering or creating solutions that were not considered in the first analysis but that may turn out to be much better solutions after all.

Finally, the Type IV error has to be questioned. The organization must assess whether various unanticipated resistances, obstacles, or unintended consequences overcame the benefits that could be potentially derived from the chosen solution. If a Type IV error is detected, steps have to be taken to implement the solution in a different way, taking the new awareness of obstacles into account.

When a full assessment has been made, the first part of step 5 is complete. The second part of step 5 involves a strategy for re-engaging in steps 2, 3, and 4, on where the errors were made. That is, a strategy is developed for performing one or more steps differently from before in order to manage the initial problem more effectively. The cycle of steps is then repeated, arriving back at step 5, where the question of whether the initial problem has been resolved is again addressed. Going through the cycle of problem management once or just a few times should resolve the initial problem or at least help to continually manage very complex recurring problems.

Figure 1 suggests that the effectiveness of a problem management effort is a multiplicative function of all five steps. That is, if a major error is made in any step, the overall effectiveness is zero (anything multiplied by zero is zero). Failing to implement the right solution (Type IV error) and implementing a solution to the wrong problem (Type III error) are probably the most obvious examples. Selecting a weak solution rather than a better solution (Type I and Type II errors), failing to sense the existence of a significant problem (Type 0 error), and incorrectly evaluating the impact of a solution on a problem situation (Type V error) are more subtle examples of the multiplicative relationship among the five steps.

BEHAVIORAL ACTION STEPS FOR PROBLEM MANAGEMENT

The foregoing discussion has outlined the generic problem-defining and problem-solving process and has defined the effectiveness of problem management in terms of the five basic steps. It is necessary, now, to relate this process to an organizational setting and to consider the specific behavioral actions by which steps 1 through 5 can best be executed. In other words, the initial view of problem management has to be expanded to include such questions as these: Who should be involved in the process? From what parts of the organization should they come? What abilities or attributes should these members have in order to engage in the process effectively? Do we need different people for different steps? How should these members be designed into organized groups so that the process can be conducted efficiently as well as effectively? How should these members interact with one another in designed groupings so that the most can be made of their expertise in addressing the problems of the organization?

Thus, although Figure 1 helps to describe and define the steps involved in problem management in some abstract sense, practicing managers and consultants need concrete principles and guidelines on how to carry out this process for problems in their specific organization. Basically, what is needed is a translation from theory to practice in order to answer the above questions. A framework (adapted from Kilmann and Thomas, 1978) will now be presented that sorts the above questions into four areas of action steps that managers can utilize in any problem situation, so the potential for effective problem management can be realized.

The four areas of action are defined by two basic distinctions: process versus structure and internal versus external. The process-structure distinction refers to the types of variables or action options available to the problem manager. Process denotes events, sequences, or episodes that take place over time among organizational members (the people who will be engaging in the generic process shown in Figure 1). Structure denotes the conditions, forces, or constraints that influence or guide behavior in organizations and may refer either to the stable attributes within people or the stable conditions existing outside people, in the environment of behavior. Consequently, while the process perspective places people in a sequence of events, the structure model places people in a web of forces as an explanation of people’s behavior or as a strategy to change or influence behavior.

The internal-external distinction refers to whether the focus for action or choice is within people, as in mental activity (process) or personality characteristics (structure), or outside people, as in interpersonal interactions (process) or organizational designs, goals, or reward systems (structures). Combining the two basic distinctions results in four possible areas of action in problem management in an organization: external-process, external-structure, internal-process, and internal-structure.

The four action areas are meant to provide a basis for translating the abstract process into problem management activity in the organization:

- Internal-structure represents the various individual attitudes, characteristics, abilities, dispositions, and beliefs that affect the steps of problem management. Certain individuals, because of their personality characteristics, may be better at sensing problems or defining problems, while other personality types may be better at problem solving and implementation. Bearing in mind the relationship between personality style and the steps of problem management will help managers select individuals from the organization to engage in problem management activities, or at least will help them appreciate how different styles are likely to address the same problem situation.

- Internal-process represents the mental activities, thought processes, or logic with which individuals “work through” a problem. Here the concern is whether individuals are applying the type of logic suited to the nature of the problem. One action area for problem managers is to help individuals think about problems in new ways and to make their analysis or thought process explicit when inquiring into alternate definitions of the problem or different solutions. For example, making one’s assumptions explicit is an important mental activity that bears strongly on the effectiveness of how different problem definitions are illuminated and analyzed.

- External-structure is concerned with the design of problem management groups—that is, the arrangement of individuals into groups as well as intergroup combinations in order to best utilize the problem management resources in the organization. Groups can be more powerful and effective than separate individuals in problem management as well as in other organizational activities. Setting up useful group structures is therefore an essential part of moving members of the organization through the five steps of problem management effectively.

- External-process concerns the interactions (processes) that take place among individuals once they are designed into various group and intergroup arrangements. Which type of interaction is most conducive to creativity, the articulation of differences, and the resolution of differences? Are different modes of interaction appropriate to each different aspect of problem management? Specifically, external-process focuses on ways in which conflicts or differences are addressed and managed, since the five generic steps have much to do with the development and management of conflict. And how conflict is handled has much to do with the quality of the problem definition as well as the acceptance of the implemented solution by organizational members.

Each of the four action areas will now be explored in more depth in order to develop specific guidelines or principles for conducting problem management effectively.

Internal-Structure

The personality typology of C. G. Jung (1923) has been shown to be quite useful in explaining the effect of individual differences in organizational settings. Specifically, the Jungian framework considers individuals as having developed characteristic ways of taking in information and then making decisions on the basis of this information. Much of organizational activity in general, and problem management in particular, includes sensing or collecting information and making decisions (choosing a problem definition, selecting an alternate solution, deciding on an implementation strategy, and so on). It is therefore apparent why this framework has received so much attention. In addition, the Jungian personality characteristics to be described below, are expected to be fairly stable attributes of people. People prefer a certain style of taking in information and making decisions. This style remains fairly constant over time and thus fits well into the action area of internal-structure.

There are two basic ways in which people take in information: sensation and intuition. Sensation refers to the preference for taking in information directly by the five senses. It focuses on the details, facts, and specifics of any situation, the here and now, the immediately tangible data, the itemized parts, and so on. In contrast, intuition is a preference for the whole rather than the parts, for the possibilities, hunches, or future implications of any situation, the extrapolations, interpolations, and any unique interrelationships among pieces of information. Thus with intuition the focus is beyond the parts; with sensation the focus is on the parts themselves. According to Jung, people develop a preference for one type of information-taking mode; and although individuals can do both if required, they cannot do both equally well, nor do they like to do both equally well—they simply prefer one over the other. In fact, the information-taking mode that is not preferred is often referred to as an individual’s blind side or his weaker function.

There are two basic ways in which individuals arrive at decisions: thinking and feeling. Thinking refers to a very impersonal, logical, analytical, reasoned preference for making a decision. If such and such is true, then this and that follow, based on logical analysis. Feeling, on the other hand, is a very personal, value-laden, unique mode for making a decision. Does the person “like” that alternative? Does it fit with his values and the image he has of himself? While the development of such a conclusion is not logical, it is not illogical either. Rather, feeling is alogical, or simply based on a different style of reaching decisions. Just as they do with sensation and intuition, individuals develop a preference for either thinking or feeling. Although individuals can apply either when required, they may be uncomfortable and simply not sure of themselves and their decision when they utilize their weaker function.

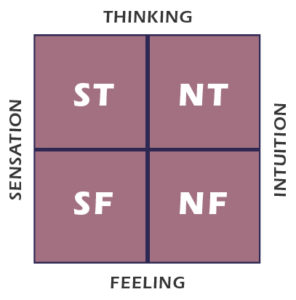

As shown in Figure 2, the two ways of information taking and the two ways of decision making, when combined, result in four personality types: sensation-thinking (ST), intuition-thinking (NT), sensation-feeling (SF), and intuition-feeling (NF). Each type represents a particular combination of an information-taking and decision-making preference that is manifested whenever individuals engage in any aspect of problem management.

Figure 2

The Four Jungian Types

ST (sensation-thinking) individuals prefer the well-structured aspects of problem management. They prefer clear-cut alternatives, supported by detailed information on every consequence of a decision, and they choose a particular alternative on the basis of a logical, impersonal analysis (such as a cost-benefit calculation). STs seek single answers to all questions and prefer the answers to be clearly right or wrong, as determined by some analytical assessment. It is not surprising, then, that STs are most comfortable with step 3 of problem management, where specific solutions are derived and, better yet, each alternative is carefully analyzed in order to pick the best solution to implement. STs are uncomfortable with uncertainty, imprecision, subjective criteria, and personal interactions, but these qualities are not germane to step 3.

NT (intuition-thinking) individuals prefer the development of many possible ways of looking at a complex situation, where each way is a broad, abstract perspective. NTs have a high tolerance for ambiguity, perhaps because they prefer not to get down to details; therefore, at a very general level, differences can be managed easily. In addition, however, NTs recognize that there are always alternative views, especially in complex situations. They get bored, in fact, with well-structured, routine types of problems. NTs therefore are generally most comfortable with step 2 of problem management, where alternative problem definitions are considered and then synthesized. Such a synthesis is facilitated by the NT’s analytical ability, if only at an abstract, theoretical level. But because of their preference for thinking, NTs require some initial structured input—perhaps an indication that some problem already exists.

NF (intuition-feeling) individuals enjoy the most ill-defined, ambiguous situations. In fact, it might be said that NFs thrive on uncertainty and ambiguity. They thus function best when there is a minimum of structure or order, or when problems have not even been defined or sensed. NFs are most comfortable in noting when something is wrong or sensing that some problem exists. Because of their preferences, however, they become uncomfortable with moving past step 1. This would take them into the more structured realm of problem management, which represents their blind side or weaker function.

SF (sensation-feeling) individuals enjoy interpersonal interactions with specific people. This satisfies their preference for concrete details as well as their personal, value-laden preference for being with people (where subjective, qualitative, and “liking” criteria are paramount). SFs enjoy the people part of problem management. They are concerned with the unique needs of particular people in the organization—rather than with analytical aspects of problem management (ST or NT) or the broad aspects of problem sensing (NF). SFs therefore are most natural for step 4: implementing solutions. Their orientation enables them to best consider the impact of the solution on the members of the organization—the kinds of needs, resistances, fears, and other unique reactions that are likely to be manifested. Such sensitivity enables SFs to guide implementation effectively.

It should be emphasized that the above description of personality types applied to problem management portrays the extremes. One should not conclude that only NFs can sense problems, NTs define problems, STs derive and choose solutions, and SFs guide implementation. Rather, these preferences as personality characteristics (internal-structure) enable certain aspects of problem management to be performed better than others. It is not that an ST cannot sense problems or guide implementation, but that an NF and SF, respectively, will be more natural at it and might do it a little better as a result. But because NF is the exact opposite of ST, the latter will have greatest difficulty in problem sensing while the former will have greatest difficulty in calculating solutions. Similarly, an SF will have the most difficult time defining complex problems, while an NT will really have to push himself in guiding the implementation of a solution.

It is not surprising to suggest, therefore, that one person or persons of only one type will have difficulty performing the entire problem management cycle. This is especially evident in step 5 (evaluation), where, if the initial problem is still sensed, each prior step has to be examined to see how well it was performed and whether any errors were made. Different steps in the cycle, therefore, require different personality preferences. Consequently, a problem manager selecting members to engage in the cycle should be guided by the following:

- Include people with diverse personality types in problem management so that resources are available to do each step in the cycle well.

- When possible, have NFs focus on problem sensing, NTs on problem defining, STs on problem solving, and SFs on implementation.

- Be aware of these different personality types and know how each contributes to overall effectiveness.

- Develop your own personality preference so that you can begin to perform (and not just appreciate) each step in the cycle.

Managing by the above guidelines is expected to facilitate a valid evaluation of the problem-solving process, since each separate step can be properly evaluated only if its unique features are appreciated and learned.

In addition to capitalizing on personality differences in members, it is important to keep in mind other criteria for selecting people to engage in the five-step process of problem management. Certain areas of expertise (for example, in accounting, marketing, and the service that the organization is providing) need to be represented in the people involved in problem management, depending on the extent and complexity of the problems in question. In other words, it is necessary to have knowledgeable people as well as certain personality types in order for problem management to be effective.

Furthermore, commitment and member involvement are fundamental in considering whether the implementation of a solution to the problem will be accepted by organizational members. The varieties of resistance to change and of forces to keep things the same were discussed in the section on step 4: implementing the chosen solution. In general, the more that individuals are involved in making decisions (or affecting decisions) of concern to them, the more likely they will be to accept and be committed to those decisions (Leavitt, 1965). Involvement fosters ownership and a feeling of oneness with the organization. Lack of involvement on matters directly relevant to the individual fosters alienation, resistance, and even rejection. Consequently, in addition to personality and expertise considerations, participants in problem management should be chosen because they will be potentially affected by whatever solutions are implemented. For complex problems, this often includes representation from most segments of the organization and even representation from outside sectors (such as clients, consumers, and lobbying groups).

The following additional guidelines are therefore offered for selecting members according to the internal-structure aspects of problem management:

- Select people who are experiencing the problems.

- Select people who have the expertise to define and solve problems in various specialties.

- Select people whose commitment to the problem definition and resulting solutions will be necessary in order for the solution to be implemented successfully, and who are expected to be affected by the outcomes of any effort to solve or manage the felt problem.

These guidelines presuppose that the problem managers can anticipate the eventual definition of the problem, its solution, and the manner in which the solution will be implemented. Naturally, if this could be done exactly, there would be little need to involve many people in the process of problem management, except for fostering commitment and acceptance. However, the Type III error is especially likely when only a few people are involved in a complex problem. Therefore, as many people as possible, drawn from general areas of expertise and related to expected issues of acceptance and commitment, should be involved in managing the problem. Perhaps even more important, as the process of problem management proceeds through the five basic steps, the selection of people can be altered as more becomes known about the problem in question. Therefore, flexibility in the selection of people with certain stable attributes (internal-structure) is the key, rather than being constrained to the initial selection decisions.

Internal-Process

Besides the relatively stable personality characteristics of people, managers must also consider what particular mental processes are relevant to problem management and how to make these processes as effective as possible. In other words, besides the fundamentally different preferences of thinking versus feeling, for example, and their relevance to particular steps of problem management, there are certain mental processes that need to take place in all steps—but primarily in problem definition and implementation. It is in these steps that Type III and Type IV errors are the most critical (compared with Types I, II, and V). Internal-process thus explores the aspects of mental activity that need to be fostered regardless if individuals are ST, NT, SF, or NF.

Assumptions in the definition of problems and the derivation and implementation of solutions are critical mental processes that are generally implicit, unconscious, or (by definition) taken for granted. Yet assumptions have a major impact on what individuals expect will happen, can happen, or should happen. Assumptions are the driving force behind the support for various problem definitions or plans for implementation. Associated with assumptions are stakeholders—individuals, groups, or any collection of individuals who have a stake in the organization in question (such as employees, stockholders, consumers, and competitors). Individuals in an organization implicitly make assumptions about what the various stakeholders want, believe, expect, value, and learn, about how they make decisions or engage in activities themselves, and about the outcomes from stakeholder decisions and activities.

Assumptions may be defined as the premises or contingencies from which certain conclusions (decisions or viewpoints) can be derived. For example, if certain assumptions are true or what is being assumed does materialize, then a particular conclusion is correct. But if certain assumptions are actually incorrect or what is being assumed does not materialize, then some other conclusion is warranted. Most often, however, individuals assume that things in the past will automatically be the same in the future, that everyone is basically the same and wants the same things, that people make decisions in a totally rational manner, that the organization is primarily interested in being maximally effective, that the clients of the organization need the particular service that the organization offers, that the clients can easily discern the value of the organization’s service, that organizational growth is always desirable, and so on. In other words, people accept very basic and sometimes simplistic assumptions, only because these assumptions have never been questioned or exposed for questioning. Yet so much of what individuals may argue for (for example, continuing to provide the same exact service to clients, designing certain advertising campaigns, proposing budget increases to offer more services) may be based on inaccurate assumptions or simply outdated assumptions. In fact, one could reverse each of the “typical” assumptions just stated (forming counter assumptions) and realize that these “atypical” assumptions are also plausible but lead to very different conclusions!

Alternative problem definitions can usually be generated quite easily by altering assumptions. Actually, being locked into a given set of assumptions can limit the likelihood of alternative definitions of the problem being entertained and seriously considered. For every different set of assumptions, a different problem definition can be derived. Furthermore, when various strategies are being considered for implementing solutions, different assumptions will again suggest different strategies. For example, assumptions regarding how those affected by the solution will react are obviously critical to how the solution is presented to the organization.

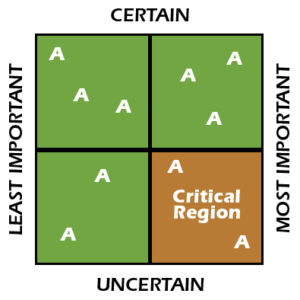

Internal-process is concerned with making assumptions explicit, questioning these assumptions, formulating new and/or counter assumptions, questioning these new assumptions, and then deriving the problem definitions and implementation strategies that follow from these assumptions. Questioning an assumption involves an assessment of its validity—now that the assumption is stated explicitly, is it true? Since truth and falsity often depend on probabilistic events or simply future happenings, part of the questioning may also involve stating the relative certainty or uncertainty of the assumption. If the assumption is very uncertain, perhaps further information should be collected or forecasting should be done to reduce the uncertainty. Finally, questioning entails an assessment of importance: How important is this assumption to the conclusion being offered (the problem definition)? Will the conclusion change drastically if this particular assumption is altered? It is clearly more critical to question the validity and certainty of assumptions that are most important to the issue at hand (Saaty and Rogers, 1976).

A sequence (primarily a mental process) that gets at the substance and questioning of assumptions might be as follows. State your definition of the problem (or strategy for implementation). Then list all the relevant stakeholders that might have some bearing on the problem as defined—either in the cause of the problem or in its solution. Formulate one or more assumptions that must be true for each stakeholder so that the definition of the problem is maximally supported and can be derived explicitly. In other words, what aspects, decisions, activities, outcomes, or beliefs of each stakeholder would have to exist to argue most strongly for your definition of the problem? (This assessment ensures that no major assumption is missed by ignoring one or more key individuals or groups that bear on the problem.)

Next, as illustrated in Figure 3, assess the importance and relative certainty of each assumption (A) in order to highlight the few assumptions that are most important and also most uncertain. Develop counter assumptions for the most important and most uncertain assumptions. (Because of their uncertainty, the assumptions can be changed easily, and they will still be plausible. Their importance suggests how changing the assumptions can significantly alter the desired conclusion.) Then develop alternative problem definitions on the basis of the counter assumptions (or variations thereof) that have now been formulated. Finally, examine each set of assumptions and its corresponding problem definition and select one set or a synthesized set in order to minimize the Type III error (defining the problem incorrectly on the basis of wrong or inaccurate assumptions) or the Type IV error, if implementation strategy is being considered. Each of the foregoing steps should be conducted in such a manner that conclusions are directly derived from assumptions—that is, what ordinarily remains hidden and therefore not subject to debate and questioning is made explicit and is examined.

Figure 3

The Assumption Matrix

This sequence of steps in assumptional analysis can be performed by one person, several people, one group, or several groups. However, internal-process by itself cannot present the whole range of action steps necessary for effective problem management in an organization. The other action areas are needed as well.

External-Structure

Most efforts at problem management make very little use of the problem-defining resources of the organization in diagnosing a problem situation and developing an implementation strategy to best address the defined problem. More often than not, one or a few managers, with or without the aid of a consultant, perform the steps of problem management. Recent research and practice in the field of organization design, however, demonstrate some alternative means to more systematically and efficiently involve members in the problem definition process by means of designing problem-defining groups. It is expected, in fact, that such structural designs (that is, external-structure) will result in a better problem definition (because a broader base of expertise is brought to bear in the process). Further, an implementation strategy to address the defined problem will receive greater commitment and involvement from organizational members, precisely because of their greater participation in the process.

More specifically, for complex, ill-structured problems there are a number of alternative definitions. These not only are feasible but are likely to be proposed and considered as the problem facing the organization by different individuals (because of specialization, selective perception, vested interests, or personality differences). However, different people proposing different problem definitions are viewed as a set of resources that can be designed into action—that is, combinations of problem managers with expressed views of problem definitions can be formed into groups to discuss, debate, synthesize, and better formulate their views. Such designed groups, moreover, are considered more powerful than separate individuals conducting isolated diagnoses of the organization. (“Powerful” means more influential owing to the greater mobilization of expertise, motivation, cohesion, and commitment that results from the proper use of groups.) Furthermore, designing more than one group and making these groups as different as possible will maximize the likelihood that different problem definitions will be entertained and fully considered. That is, each group will develop a distinct definition of the problem. These definitions can then be debated and synthesized.

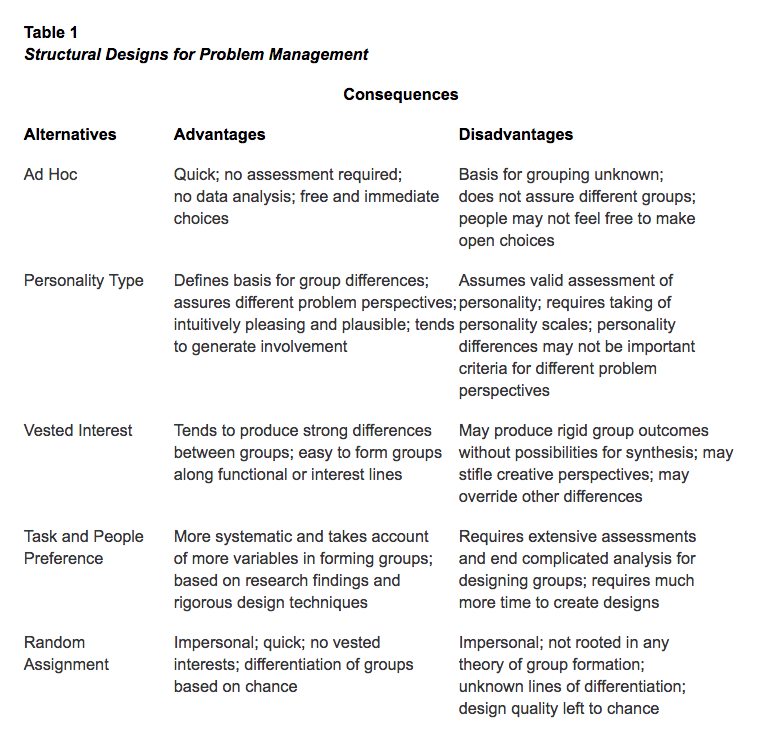

Table 1 shows five structural designs for problem management groups. Each group design has these aspects in common: (1) designing individuals into various groups; (2) having each group formulate and present its views on what is causing various problems in the organization; (3) debating different views, assumptions, and beliefs across the several groups; and (4) developing a synthesized statement of the problem situation. What varies across the different designs, however, is that each type of group structure has its corresponding advantages and disadvantages.

Following is a brief summary of each design alternative: The assumption is that a variety of individuals throughout the organization (or subsystems) in question have been brought together to participate in problem management. Also, even though the external-structure action areas can be formulated for each of the five generic steps in problem management, the discussion concentrates on designs for problem definition, since this is viewed as one of the most critical contributions of external-structure (that is, managing the Type III error).

The ad hoc design. A collection of individuals is asked to generate, either separately or in small groups, a list of problems that they are experiencing in the organization. The total list is then categorized into major themes: by type of problem or by functional area in the organization, by those affected by the problem (or by some other categorization that seems useful in highlighting different ways of conceptualizing the organization’s problems). This categorization then becomes the basis for forming problem-solving groups—groups that are to spend time in further defining the problems listed under the various categories, debating their views with other groups, and so on. Individuals are designed into these groups by task preference. That is, each individual chooses to work in a particular group on the basis of his or her preferences for the categories of problems. The group size is regulated by asking individuals in the larger groups with marginal or multiple interests to switch to the smaller groups.

The ad hoc design is fairly easy to utilize since it requires no formal assessments of interest. Rather, as problem types emerge, individuals self-select into groups. Balanced against its ease of use, however, is the uncertainty of who determines (and how) the problem categorization that is the basis for group formation and differentiation. It may be the consultant, the top manager, or a few vocal individuals who propose the categories, but the process is likely to be less than systematic and all-encompassing.

In essence, the important task of forming ad hoc groups is first based on an unsystematic method of categorization coupled with individual preferences to be in a particular group (working on a prespecified category of problems). While the latter is likely to foster commitment (because of choice), one cannot be sure that the individuals in each group will work well together—since it is only task preference, not people preference, that determines group composition. The importance of this design issue will be evident later as the other designs for external-structure are discussed.

The personality type design. Instead of allowing individuals to self-select into groups or to let some unsystematic categorization of problem items determine the task focus for each group, individuals can be distinguished on some personality dimension that is considered salient to organizational diagnosis. Different types of personalities might be expected to define and view problems quite differently, and such a distinction could well contribute to designing different problem-solving groups. Naturally, the choice of both the personality scheme to use (and the measuring instrument that is applied to assess individual personality types) is critical. The instrument must be reasonably valid and reliable, and the personality dimension must distinguish important problem perspectives.

Most research on organizational behavior has shown that individual differences do not play a major role in what takes place in organizations. Nevertheless, the psychological typology developed by C. G. Jung, as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Myers and Briggs, 1962), has proved to be a useful framework for problem definition purposes. Specifically, in 10 to 15 minutes, individuals can be assessed and sorted into the four personality groups discussed above. These four groups usually present four very different views of a complex problem situation and, since the psychological typology is quite broad and encompassing, the four designed groups tend to consider most of the important issues in the situation.

An advantage to using the personality type design is that since the basis of group differences is known, the results of the group can be predicted to a certain extent. Moreover, the participants tend to get involved in the problem-solving process because of the intuitively pleasing basis for categorization and its uniqueness to most organizational members.

A disadvantage of the personality-based design is that some individuals do not like taking “personality tests,” consider them an invasion of privacy, and view the assessment as invalid (“You can’t sort me into a group on the basis of that test!”). Since personality scales and measurements are not 100 percent valid, there is some truth to these opinions. It is also possible that the personality framework selected to distinguish groups is not appropriate to highlight important aspects or different views of the problem situation. In some situations, no personality framework may be appropriate, and in that case some other basis for designing groups might be much more powerful in bringing out differences in viewing the problem situation. But whether or not the personality type design is chosen (external-structure), members may be selected partly on the basis of personality attributes (internal-structure) so that each generic step of problem management can be done well.

The vested interest design. Different definitions of what constitutes the organization’s major problems are often rooted in identifiable, already existing groups. For example, functional areas in the organization, service departments, professional or disciplinary associations, and simply memberships in am ongoing group may greatly determine the way individuals will perceive the organization’s problems. The vested interest design attempts to make the most of these natural or ongoing differences. Thus, groups are designed by explicitly maintaining existing group memberships (for example, nurses versus doctors versus administrators) in order to generate the correct problem definition. What has to be decided, however, is which set of vested interests should be the basis for a particular design. Should it be functional area, disciplinary training, management versus worker, or something else?

Consequently, one disadvantage of the vested interest design is that it assumes that the critical vested interests are apparent in any situation. However, this is often not the case. And just as the personality-based design can err on the side of choosing an inappropriate dimension of personality to distinguish groups, so the vested interest design can choose the wrong vested interest groups. Another disadvantage of this design is that very strong vested interest positions may result, with little or no probability of developing integrated or synthesized viewpoints. The separate groups may rigidly stick to their initial positions. The same rigidity may also stifle creative or new perspectives, since the groups may become locked into stereotyped attitudes. In other words, some other design of groups could possibly foster new ideas instead of the status quo.

But if the differences between the vested interest groups do not become overwhelming, the organization can depend on the strong expression of different viewpoints with this design alternative. Also, if groups already exist along clear interest lines, it certainly is easier to form these groups than to utilize personality tests or rely on unsystematic methods of problem categorization (as in the case of the ad hoc design). Finally, individuals are generally quite comfortable in their natural interest groups in contrast to some other, less familiar form of group composition. Membership in an interest group, at a minimum, does provide a strong support base for individuals.

The task and people preference design. This design is probably the most complex in terms of the number and variety of variables taken into account. In essence, individuals indicate those fellow organizational members they can best interact with in a problem-defining group as well as their problem and task preferences. Individuals with similar preferences are placed in the same group.

The dimensions of tasks and people are chosen because of the support in the literature for these two general types of variables in determining effective group behavior (Blake and Mouton, 1964). Briefly, a group can be expected to have difficulty in completing its assignment if members do not have some similarity or compatibility of viewpoints to suggest what tasks are important. On the other hand, if the individuals within a group can agree on what issues are critical to defining the organization’s problems but cannot get along with one another and therefore cannot form into a cohesive group, it is unlikely that the group will make the most of its expertise and other member resources. Consequently, the effective group must be designed from certain task and people similarities. Further, to maximize the motivation and commitment of each group under this design, the members themselves are expected to choose the relevant task and people characteristics on the basis of their preferences and beliefs, rather than having some outside consultant or other person assign people to a group without their participation in the design decision.

The task and people preference design thus goes beyond the ad hoc design in that it is determined by both task and people considerations. However, rather than having one or a few people perform the group design in a qualitative, ad hoc manner, the task and people design can be conducted by the MAPS Design Technology—a computerized procedure for systematically using individual responses to task and people questionnaire items in order to efficiently cluster individuals into groups. The computer process is designed to draw out similarities in task and people preferences from the inputs of all individuals participating in the problem management design (Kilmann, 1977).

The major advantages of the task and people preference design include the systematic integration of task or problem issues and the formal consideration of task and people dimensions in designing groups. Utilizing the MAPS procedure with the aid of a computer facilitates the analysis of many variables that separate individuals cannot calculate, let alone comprehend. Also, because of the impersonal nature of the computer, the resultant design stems not from a few individuals’ perceptions, but from the inputs of all individuals.

The primary disadvantage of this design is its complexity. It takes much more time to form the groups, and individuals typically need some preliminary understanding of how the process works (particularly if MAPS is used) before they can become committed to the design. Furthermore, while the impersonality of the computer is an advantage to some (because it may appear to be more objective and certainly more systematic), others meet it with disdain (“I am not going to let some computer program determine what group I get assigned to, whom I work with, and what I work on!”).

The random assignment design. Individuals may also be assigned to groups strictly on a chance or random basis (as in a control group for research purposes). The advantages of random assignment are that it is impersonal, is easy to administer, takes little time, and by chance can be expected to form groups composed of diverse people so that strong functional vested interests are not localized in a single group.

One can expect, however, a number of disadvantages or negative consequences to this design method. First, its very randomness does not allow one to define how each group is differentially designed. Therefore, it is not at all certain whether groups will in fact develop different perspectives. It is conceivable that all differences, in the extreme, are randomly distributed across the groups. Thus the important differences regarding the definition of organizational problems become suppressed in the process of each group developing a consensual position to debate with the other groups (that is, the groups may turn out to be quite similar). Second, while the random process may seem impersonal and not tied to vested interests, it is also seen as devoid of substance. That is, groups are not designed according to some substantive theme, whether derived by ad hoc categorization of issues, personality types, vested interests, or a computer analysis of problem issues via questionnaire responses. Some individuals see the random design process as a “copout” in attempting to structure problem management.

A comparison of designs. The foregoing discussion has summarized five alternative designs for problem management. While other structural designs are certainly plausible (designs based on age, sex, hierarchical level, values, and so on), the five designs discussed demonstrate the variety of ways in which the organization could increase the likelihood of obtaining a correct problem definition and commitment to implementing solutions to the identified problems.

When presenting even five alternatives, however, one must consider a meta-theory: a set of principles for selecting each design under particular circumstances. This assumes, of course, that the five designs are not all equal but have advantages and disadvantages for the organization. It seems appropriate, therefore, to briefly consider some guidelines for selecting the different designs.

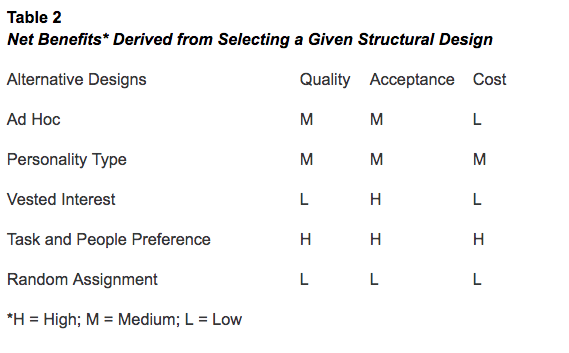

Table 2 compares the five designs according to three criteria: (1) the cost or energy involved in implementing the design (including assessments and analysis of assessments, relatively speaking), (2) the expected quality of the problem definition based on the likelihood of different viewpoints and a well-balanced synthesis of these viewpoints, and (3) the expected commitment and acceptance generated by organizational members as a result of the type of individual participation anticipated by the design, compared to an average level of commitment fostered by participation in any group design.

Criteria 2 and 3 follow from a very basic model of group effectiveness—that is, effectiveness = quality of decision x acceptance of decision (related to Type III and Type IV errors. respectively). The multiplicative relationship emphasizes again that if either component is low or zero, so will be total effectiveness (anything multiplied by zero is zero). Criterion 1 recognizes that there is a cost (energy usage) associated with the implementation of each structural design in terms of individual assessments, data analysis, time for explaining results of personality variables, addressing questions concerning the use of more complex designs, and so on.

Assuming that appropriate scales could be developed for the three criteria, one might propose a general equation as follows, where criteria 2 and 3 represent potential benefits to a given design and criterion 1 represents its costs:

Net benefits derived from a given design = (quality x acceptance) – costs

In each cell of Table 2, a qualitative assessment has been made of high, medium, or low to reflect the advantages and disadvantages of each structural design. For example, the random assignment design scores low in terms of costs of implementing, but is also low in quality and acceptance. In contrast, the task and people preference design is the most costly to implement but it is also expected to have high quality and acceptance because of its systematic and involving nature. The vested interest design is high in acceptance, since the design follows preexisting groups; but it is expected to be low in quality, since a creative synthesis across strong vested interest is not expected. However, the vested interest design is relatively easy to implement. The ad hoc design is expected to have many of the same benefits as the personality-based design, but the latter is a bit higher in costs of implementation.

Although it would be tempting to compare the five designs and to select one over the other for all situations, it must be emphasized again that the scaling in Table 2 is very rough, qualitative, and based only on gross expectations. In addition, different organizational situations or climates would weigh each of the three criteria differently. Thus, in one situation quality rather than acceptance might be the most important criterion, especially if organizational members are willing to utilize any of the five designs. In a different organizational setting, however, the cost factor might be critical. For example, members may be skeptical or resistant to any design other than the ad hoc because they do not “believe” in personality theory, computer analysis, or any other type of systematic method of group composition. In this case, a substantial cost would be evidenced that would offset the benefits to be derived from using the personality type or the task and people preference design.

A number of guidelines will now be summarized to aid the action steps in the external-structure area:

- Developing the correct problem definition, the best implementation strategy, and other decisions in problem management can be aided greatly by the use of group structures rather than simply individual efforts, particularly for complex problems.

- Groups can be composed along a number of dimensions (for example, personality type, vested interest, ad hoc), but the choice in a particular situation should be based on what composition will make the separate groups most different with regard to the issue at hand (for example, problem definition), while also being open to a creative synthesis. The chosen design should also not be too costly given the climate and resources of the organization.

- Once the separate groups are formed (a manageable number is three to six groups, each containing four to seven members), each group is expected to develop a position statement, a preliminary problem definition, or an implementation plan in a reasonable period of time. Then a debate among the groups is encouraged in order to set the stage for a synthesis—helping members to understand the reasons for the group differences and the advantages and disadvantages of each position. Finally, representatives from each group meet to form a synthesis group (or several synthesis groups). The objective is to develop a creative synthesis by maximizing the advantages or strengths of each position while minimizing the disadvantages or weaknesses.

Utilizing group design as suggested above is expected to make the most of the problem management resources of the organization, not only to derive a higher-quality definition and solution to the problem, but to provide for a successful implementation program.

External-Process

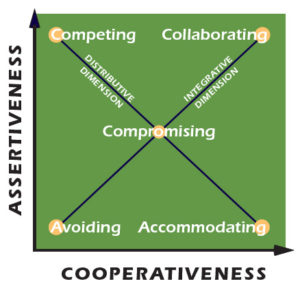

The fourth and final action area, external-process, concerns the interactions (processes) that take place between individuals (external) once they have been designed into various group and intergroup structures. Of the several possible conceptual frameworks for understanding the nature of interactions and interpersonal processes, conflict and conflict management (Thomas, 1976) would seem to be most relevant to the present discussion. In essence, at each step of the generic process of problem management there is the likelihood that conflict will be experienced—different people will propose different definitions of the problem, different solutions, and different strategies for implementation. The action areas presented previously emphasized the need to generate and highlight differences. Differences in group problem definitions (external-structure), differences in assumptions (internal-process), and differences in personality types (internal-structure) were all viewed as valuable resources to effective problem management—if these differences could be utilized constructively. Conflict is the experience of these differences, and conflict management is the manner of addressing or managing these differences constructively.

The focus of this section, therefore, is on the alternative ways in which people can approach situations (interact) when they find moderate or even extreme differences in viewpoints (including objectives, beliefs, assumptions, perspectives, values, and attitudes). The concern is to specify which of these alternative ways of approaching conflict is best for each of the five generic steps of problem management, or at least to suggest which alternative ways of interacting are more likely to result in the constructive use of conflict.