17 Jun How Your Written and Oral Communication Can Produce—or Reduce—Extreme Polarization

Ralph H. Kilmann, co-author of the Thomas-Kilmann Instrument (TKI)

Over the course of many years, I gradually came to realize that the particular words and phrases that a person uses to talk about (or write about) their core beliefs on any topic—specifically, whether they acknowledge the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY in the universe—has much do with whether other people (1) immediately ignore (and perhaps even demean) what was just communicated to them or (2) are wide open to fully incorporating those recent statements into their own knowledge base and belief system. I will now elaborate on what I mean by acknowledging uncertainty in all kinds of communication.

As a former university professor (and thus as a former doctoral student), I had to learn to include in my oral and written statements particular phrases that explicitly recognize the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY of the scientific process in today’s world, the uncertainty of the knowledge that is produced by that scientific process, and the uncertainty of any evidence that seems, at the moment, to support our theories, hypotheses, arguments, and assumptions. As a doctoral student, I learned that you could never PROVE the validity of any theory or hypothesis; you can only REJECT a theory/hypothesis or FAIL TO REJECT a theory/hypothesis. Why? Whatever one believes for the time being might, sometime later, be entirely falsified by a newer theory that does a much better job of predicting and/or explaining the phenomena of interest (often called a new “paradigm”), until another alternative theory is proposed that better predicts and/or explains the subject of interest. Through this ongoing scientific process, we test, revise, refine, and further develop our theories and hypotheses so we can enhance our storehouse of valid and useful knowledge about the universe—and especially about ourselves.

Given that the scientific process can never PROVE anything per se, consider some of the particular phrases that doctoral students are expected to use in order to convey what they know—and what they don’t know—about the topic in question: “It appears that… It seems that… It might be that… I haven’t done the research myself, but my current understanding of the controversy is as follows…. “

Now compare those kinds of “uncertainty acknowledging words and phrases” with the following dogmatic statements, whereby one’s opinions or beliefs are expressed as 100% factual, indisputable, and already proven to be true, even when there is little or no evidence to support or reject such assertions: “This is WHAT happened… This is WHEN it happened…. This is WHO did it… This is WHY they did it… This is HOW they did it…”

Such dogmatic phrases do not acknowledge UNCERTAINTY; indeed, these latter phrases make it seem that the communicator already KNOWS the total truth of “what, when, who, why, and how” and has somehow proven that without any room for doubt. It’s as if the person is proclaiming: “There is only one truth, one PROVEN theory… and I know what it is,” since such dogmatic oral and written communication actively discourages any kind of open discussion on alternative beliefs, alternative theories, or alternative explanations.

Let’s now consider the INHERENT INSECURITY that afflicts all human beings to one degree or another: While some people are more confident and self-assured than others, I find it fairly safe to assume that every person experiences some INSECURITY and UNCERTAINTY about who they are, their self-value and self-worth, and whether or not they will be liked and loved by others. I have found that people’s misgivings about their self-value and self-worth then compels them to NEED other people’s opinions and beliefs to be similar if not identical to their own—to affirm their very existence as well as the value of their existence.

Indeed, if you believe what I believe, we must both be right. If we are both right about something central to our lives, we can then feel more self-assured about who we are and be more confident that we actually have an accurate perception of reality. But the extent to which I question my self-value and self-worth, if you disagree with me on anything that matters to me, that disagreement will likely make me feel even more insecure about who I am and whether I am a likeable and loveable person.

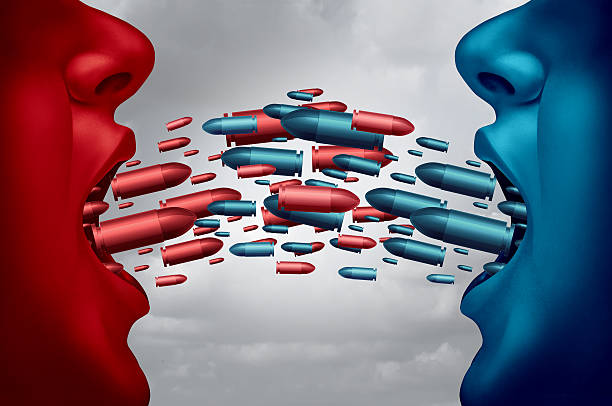

In the early 1950s, Solomon Asch1 conducted a simple experiment to investigate just how powerfully “a group” can influence the beliefs of its members. The experiment was presented to subjects as a study in perception. Three lines—A, B, and C—all of different lengths, were presented on a flip chart in front of the room. Subjects were asked to indicate which of these three lines was identical in length to line, D, displayed on another flip chart that was positioned right next to the first flip chart.

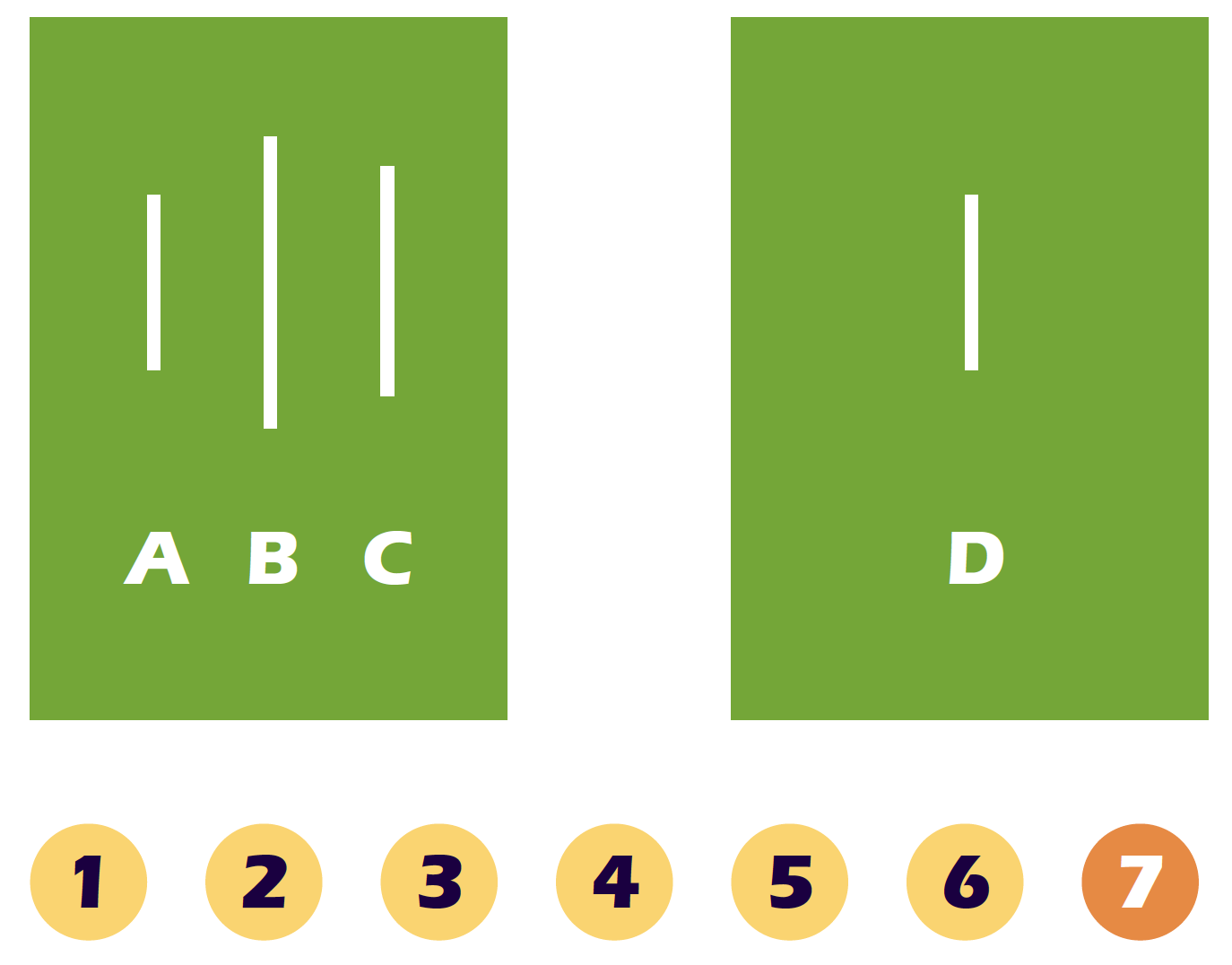

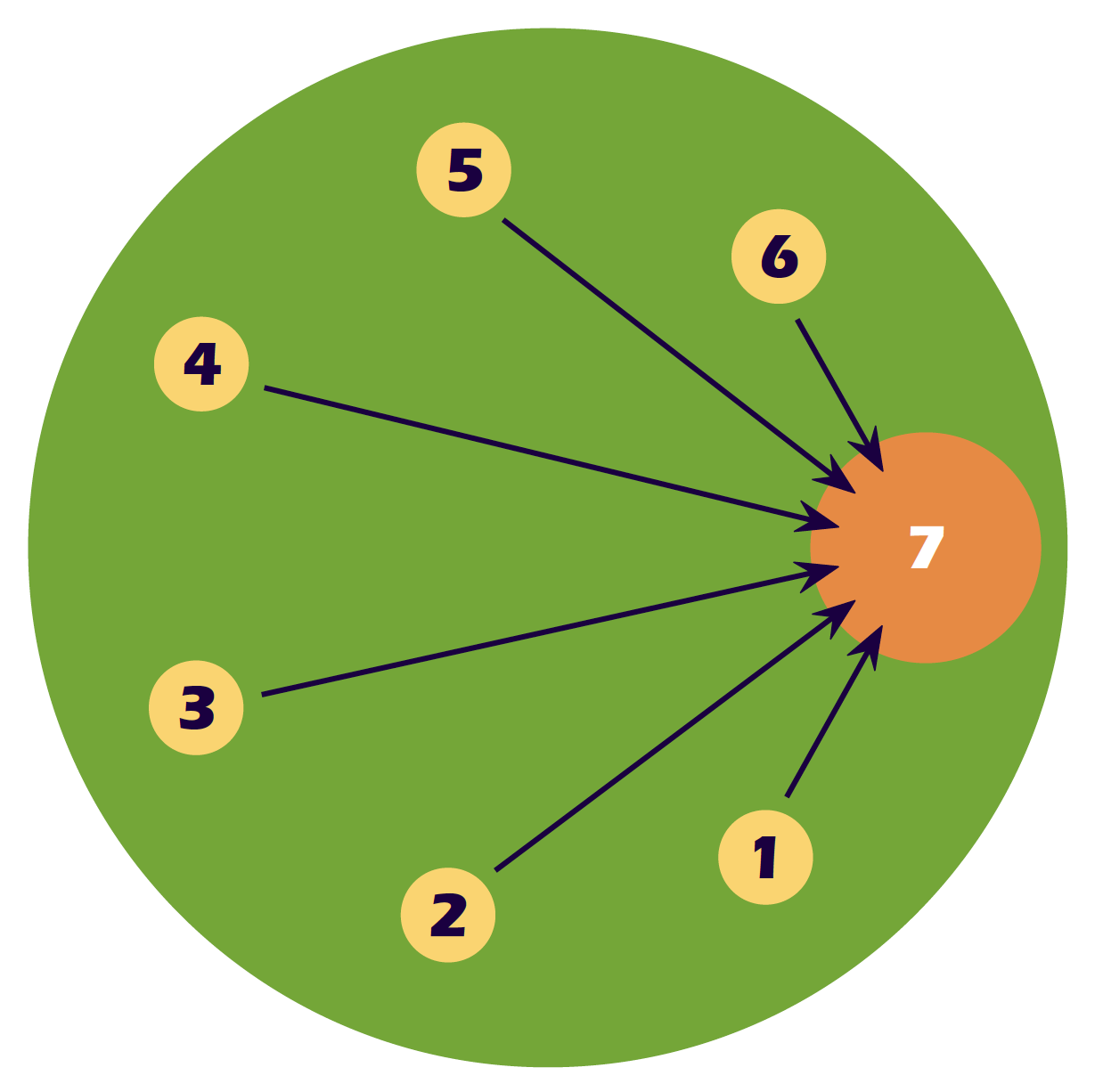

As illustrated in Figure 1, seven persons sat in a row. One by one, they indicated their choice. While line D was in fact identical to line A, each of the first six persons, confederates of the experimenter, reported that line D was identical to C. The seventh person in the row was the only unknowing subject. As the six confederates, one by one, each announced the agreed-upon incorrect response, the unknowing subjects became increasingly uneasy, anxious, and doubtful of their own perceptions—and sense of reality. When it was their turn to respond to the length of those lines, the unknowing subjects seated in Position 7 agreed with the fraudulent responses from those six confederates about 40 percent of the time. When no other persons were present, the subjects chose the wrong line less than 1 percent of the time—a research finding that has been replicated again and again.

Figure 1: Asch’s Experiments on Social Reality

In this social psychological experiment, there wasn’t any opportunity for the seven individuals to discuss the problem among themselves. However, if there had been such an open discussion among the individuals, the effect would likely have been much stronger, because the six confederates would attempt to influence the seventh person to see things their way.

As illustrated in Figure 2, it’s not easy being the sole deviant in a group (i.e., sitting in Position 7) when everyone else appears to be against you. As I noted earlier, it seems that every human being has a need to be accepted by the group—family, friends, coworkers, or neighbors—which gives a group leverage to demand compliance with its belief system. If people did not care about being accepted by others and had little or no fear about being rejected from their Tribe, a group would have little hold, other than formal sanctions, over its individual members. Most people, in fact, will deny their own perceptions when confronted with the group’s beliefs of “objective” or physical reality. Physical reality thus becomes a social reality. As such, we now enter the world of TRIBALISM: strong in-group loyalty that can significantly distort each member’s perceptions of reality in a particular direction.

Figure 2: Group Pressures on the Deviant Member to Distort Reality

Now consider when a discussion is not just about estimating and comparing the length of four lines on two flip charts but, instead, involves highly subjective, emotional, and complex problems, such as the validity of the 2020 presidential election, the safety of the latest COVID vaccines, the existence of systemic racism, whether to defund police departments, or the solution for gun violence in our schools. When discussion topics are highly subjective, the compliance for individuals sitting in Position 7 would probably increase to well over 90%, especially if the six other group members put considerable social pressure on the deviant to conform with the Tribe’s beliefs and perceptions about highly complex and emotional topics.

Let me repeat this most-important principle: If you see a troublesome situation the same way as I do (let alone if several people agree with my beliefs about what, when, who, why, and how), then I can relax and feel that I am a good person who’s sane and functioning well. Just consider how people tend to smile whenever they receive “likes” or some positive response on something they recently posted on a social media platform: “If others like what I just posted, I must be right about my beliefs and facts.” As powerfully demonstrated by the Solomon Asch experiment, if several people agree with us, we are likely to regard our beliefs as absolutely true, right, accurate, and meaningful. If anyone continues to think otherwise, that deviant must be dead wrong and, therefore, should immediately be banished from the Tribe.

Relying on other people’s similar views (and “likes”) to enhance the confidence and certainty of our own beliefs tends to motivate us to spend most of our time with people who see the world the same as we do. Not surprisingly, surrounding ourselves with like-minded friends, colleagues, and connections further reinforces our beliefs that we know the TRUTH about any relevant topic. As such, we no longer have any reason to acknowledge UNCERTAINTY in the world. In time, our language becomes even more dogmatic, as we express our beliefs in the most certain, most absolute, and most extreme terms possible: THIS IS WHAT HAPPENED AND WHY! NO IFS, ANDS, OR BUTS!

Tribe 1 firmly believes that it has spoken the single TRUTH about something, so there is no room for further debate or dialogue with Tribes 2, 3, 4, and so forth.

Let’s now consider what unfolds when people from other tribes read or hear what Tribe 1 has proclaimed as the ultimate truth on any complex and messy problem: Given my insecurities (and remember, we are ALL insecure to some extent), when I hear a person from another Tribe speak with complete certainty about their beliefs, that makes me feel even more insecure, since I am left wondering how can someone else see reality so differently from me. Am I wrong in my beliefs and my view of the situation? If the other is so right, I must be so wrong! Such black-and-white thinking is a result of not acknowledging the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY in the universe… thereby ignoring the very large gray area that exists between the extremes of black and white, right and wrong, and true or false.

As a result, whenever a person feels that they must defend the credibility or validity of their oral or written statements, they typically restate their beliefs with words and phrases that convey even more certainty, conviction, and “scientific proof” than before, as if their resounding confidence in their own beliefs (and how forcefully and loudly they proclaim them) would somehow negate the fundamentally different beliefs (and evidence) that members from other Tribes express with equal certainty and conviction. As each Tribe gradually becomes more and more dogmatic about its own belief system, each Tribe might also vocalize abusive comments (often laced with foul language) to characterize what the other tribes are saying on the same subject.

This vicious cycle then produces an EXTREME POLARIZATION that might even be backed by threats of violence or actual physical violence. Different Tribes thus become increasingly locked into a narrow worldview, defending themselves verbally (and physically) against any contradictory beliefs, factual claims, and alternative explanations of cause and effect. Oftentimes, various conspiracy theories are creatively fabricated and then aggressively disseminated as each Tribe attempts to seize control of reality. Indeed, people are inclined to say and do all sorts of things just to feel more normal, mentally healthy, accepted, respected, and loved by others. Welcome to the human race!

On occasion, it seems that some human beings are even prepared to kill other human beings just because of their radically different points of view on complex and challenging topics. When Tribes become locked into such polarized beliefs as supported by language that expresses 100% certainty and conviction, we have the seeds of CIVIL WAR, which includes the collective desire to destroy any Tribes with different belief systems, which includes destroying their property and all their belongings—so as to nullify their entire existence. Before you know it, we have recreated the current divisiveness and EXTREME POLARIZATION between the far right and the far left of our political system, which implicitly encourages domestic and international violence.

If there will be a WW III, it will likely be initially fueled by the polarized conflict among contradictory belief systems held by different Tribes—which is further fueled by the abundant fear and overwhelming stress that are usually rampant during economic crises, pandemics, all incidents of social and racial injustice, as well as military invasions of other countries.

And yet, I am firmly convinced that if every Tribe of like-minded people (whether Democrats, Republicans, for-or-against abortion, for-or-against vaccination, Jews, Christians, Muslims, etc.) used explicit phrases in their written and oral statements to convey the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY of all matters complex and controversial, everyone would be more at ease, have less reason to be defensive, feel more respected by others, and then openly acknowledge that different people are bound to experience events differently, based on their unique journey through life.

As different Tribes acknowledge the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY in today’s world and the INHERENT INSECURITY that afflicts all human beings, inter-Tribe bridges might be formed (i.e., a safe haven) that will enable those previously warring Tribes to interact with one another in a more relaxed, peaceful, open-minded, and open-hearted manner: Instead of anger, fear, pride, arrogance, and dogma ruling the day, a diverse community of different Tribes that fully acknowledges everyone’s UNCERTAINTY and INSECURITY will soon discover that they can successfully address their complex challenges when they are finally able to radiate love, joy, peace, and compassion—which WILL, ultimately, create a better life for everyone.

Despite the enormous potential for creating a healthy bridge between two or more previously warring Tribes (by explicitly acknowledging UNCERTAINTY and INSECURITY during every oral and written communication), I must acknowledge that some Tribes may be past the point of no return: It seems there will always be some Tribes that have been totally effective at RADICALIZING (brainwashing) their members with an onslaught of relentless conditioning and constant social pressure (as depicted in Asch’s experiment on social reality). As a result, such RADICALIZED Tribes might “never” be open to listening and learning from the members of any other Tribe that supports a different belief system.

Not surprisingly, it’s easier to RADICALIZE the members of a Tribe when they are particularly INSECURE about their self-value and self-worth, such that it would be much too threatening for them to even consider the remote possibility that another belief system (being expressed by another Tribe) might be more in tune with the times and also more in tune with reality. For some vulnerable people, in fact, it would be virtually impossible for them to admit that their long-standing thoughts, feelings, and behavior are actually rooted in fictitious assumptions about what, when, who, why, and how on any controversial, complex, messy social issue. Said differently: What will it take for RADICALIZED persons (who are so INSECURE that they cannot embrace any kind of UNCERTAINTY in their belief system) to admit to themselves (and all others) that they have been thoroughly conditioned, thoroughly coerced, and perhaps effectively misled to perpetuate their seriously distorted perceptions of what, when, who, why, and how? For highly INSECURE persons (perhaps further derailed by experiencing mental illness of one kind or another) to change the course of their lives might be close to impossible.

Moreover, living with certain kinds of MENTAL ILLNESS might make some members especially attracted (and thus more vulnerable) to RADICALIZATION in the first place, since their fellow RADICALIZED members would then provide them with a close-knit community to justify and defend such dysfunctional—if not destructive—belief systems. In essence, different forms of MENTAL ILLNESS are simply different ways of (a) distorting reality (via one neurosis or another) or (b) losing contact with reality (via one psychosis or another), which thus supports the serious distortions and breaches of reality that are the hallmark of every RADICALIZATION process.

Nevertheless, it’s vital that all Tribes are initially considered as potential sources for enhancing everyone’s knowledge and understanding of “what, when, who, why, and how” on all matters that pertain to society’s survival, success, and wellbeing. Not until we have convincing evidence that any particular Tribe has been RADICALIZED BEYOND REPAIR, is it reasonable to define that Tribe as either “mentally ill” or “too far gone.” But once we have accumulated convincing evidence that MENTAL ILLNESS and/or RADICALIZATION are solidly at work in a particular Tribe, we must then take the necessary steps to confine (isolate) that dysfunctional Tribe and their dysfunctional members so they are no longer in a position to harm others. To repeat: It’s not a resourceful (or compassionate) practice to quickly label another Tribe as hopelessly—and permanently—dysfunctional without a good deal of convincing evidence that’s gathered over a suitable period of time.

I remember an old story about a White Man and an American Indian that takes place in the mid-1800s. The White Man insists that the American Indian has little knowledge about the world as compared to the more educated, technologically advanced, dominant, White Tribe (e.g., having developed guns and bullets instead of relying on “primitive” bows and arrows).

To emphasize his point, the White Man uses a wooden stick to draw a very small circle in the sand that is about 1 foot in diameter, which is meant to symbolize the American Indian’s supposedly limited knowledge about everything. The White Man next draws a much larger circle (about 5 feet in diameter) that easily encompasses the Indian’s much smaller “circle of knowledge.” The White Man then states that while the Indian possesses very little knowledge (all of which can be contained within that very small 1-foot circle), the White man knows much, much more (as symbolized by that larger 5-foot circle).

At this point, the American Indian picks up another wooden stick and draws a much larger circle in the sand (this time, about 25 feet in diameter) that easily encompasses both the Indian’s small 1-foot circle as well as the White Man’s larger 5-foot circle. Pointing back and forth from the 1-foot circle to the 5-foot circle, the Indian proclaims: “This is what we both know.” The Indian then points to the 25-foot circle that is much, much larger than both of those two smaller circles combined, and proclaims: “This is what we both do NOT know!”

Essentially, the difference between the two smaller circles and the much larger one represents UNCERTAINTY, since we don’t know what’s there. Indeed, we don’t even know what we don’t know. If both the White Man’s Tribe and the American Indian’s Tribe begin to acknowledge that UNCERTAINTY in all their oral and written communications, each will likely feel more respected, be more comfortable with any disagreement, and be more inclined to work together in search of greater knowledge and truth for the best of both worlds.

People have asked me how I came to appreciate the importance of always acknowledging the INHERENT UNCERTAINTY and the INHERENT INSECURITY in every form of human communication, regarding any belief or account of what, when, who, why, and how something actually happened. Somewhere along the way of my personal and professional journey, I realized this fact of life: If instead of my having been born and raised in New York City, I had been born and raised in a remote village in Central Africa, I would surely have developed (acquired) very different attitudes, beliefs, and values than people who were born and raised in New York City, and I surely would explain any what, when, who, why, and how very differently than they do!

Knowing just how much every human being is conditioned (domesticated) by their local Tribe, whenever I hear a member from another Tribe in America (or another Tribe in Africa) state a belief about anything (whether opinion or fact), I now realize that if I had been born and raised in THAT other Tribe, I’d also be voicing the same exact beliefs as that Tribe’s long-standing members. Knowing this, it’s quite impossible for me to conclude that my beliefs are absolutely right and another person’s beliefs are obviously wrong, since I’d be putting down my own beliefs… if I had actually been born and raised in that other (African) Tribe.

Yes, it’s so important to realize just how much we human beings have been conditioned by our family, friends, neighborhoods, schools, and places of work to believe particular things with great confidence, and then, to top it all off, we are prone to choose friends and live in communities that further reinforce the validity of our very limited belief system, just so we can feel more confident that we are okay and that we are in touch with reality. And yet, if we can learn to always acknowledge that INHERENT UNCERTAINTY in the universe and our own INHERENT INSECURITY in every kind of human communication (especially with those who belong to other Tribes), we’ll be more likely to listen and learn from diverse others (regardless of which Tribes are involved in the dialogue), instead of instantly dismissing and demeaning other Tribes as being insane and evil—or even worse.

- Asch, S. E. “Opinions and Social Pressure,” Scientific American, November 1955, pp. 31–34.

Kilmann Diagnostics offers a series of eleven recorded online courses and nine assessment tools on the four timeless topics: conflict management, change management, consciousness, and transformation. By taking these courses and passing the Final Exams, you can earn your Certification in Conflict and Change Management with the Thomas-Kilmann Instrument (TKI). For the most up-to-date and comprehensive discussion of Dr. Kilmann’s theories and methods, see his 2021 Legacy Book: Creating a Quantum Organization: The Whys & Hows of Implementing Eight Tracks for Long-term success.