10 Apr Designing Collateral Organizations

by Ralph H. Kilmann

This article was originally published in Human Systems Management, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1982), pages 66-76.

ABSTRACT

A number of different design alternatives are distinguished according to whether each is best for addressing a well-defined or an ill-defined problem. The latter is reserved for a collateral design, one that coexists with the formal, operational design but is structured as a flexible, open, loose, “organic-adaptive” system of problem-solving groups. A number of key steps are presented for designing such a collateral organization so that the operational design and the collateral design will combine to sense problems, define problems, derive solutions, and implement solutions. The paper concludes with suggestions for researching some of the major ideas and principles that were offered.

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary organizations are facing increasingly dynamic and changing environments, which pose more complex and ill-defined problems than organizations have previously had to address. These problems include: which new international markets to explore, which new technologies should and can be developed, whether organizational goals should be altered, how employees should be motivated more effectively, what social responsibility policies the organization should formulate and implement. But these problems involve the entire organization, not just one or two departments or divisions, and these problems can never be completely resolved since they are always present. Thus, these problems must be managed continually. Furthermore, the information needed to analyze these problems is not generally available nor will the information ever be complete—because the nature of the problem keeps changing. In fact, one might argue that the basic problem is defining what the problem is; then one can begin seeking information, analyzing the problem, and deriving and implementing solutions to manage the problem [9].

Organizations, however, are designed more to perform day-to-day activities and to produce well-defined products and services—not to solve complex and changing problems. In particular, organizations are designed into operational subunits (e.g., production, marketing, finance, etc.) to pursue well-defined goals and tasks. But how can the organization engage in effective problem solving if it is designed primarily for day-to-day concerns and if complex problems simply do not fit well into the design categories or boxes on the organization’s chart? What is needed is a different approach to organizational problem solving—one that may involve the entire organization or at least those persons who are directly affected by complex problems, and one that specifically designs for problem solving. Further, the resultant design should structure objectives, tasks, and people in a manner that does not confine the organization to address complex problems within the day-to-day, operational design [9].

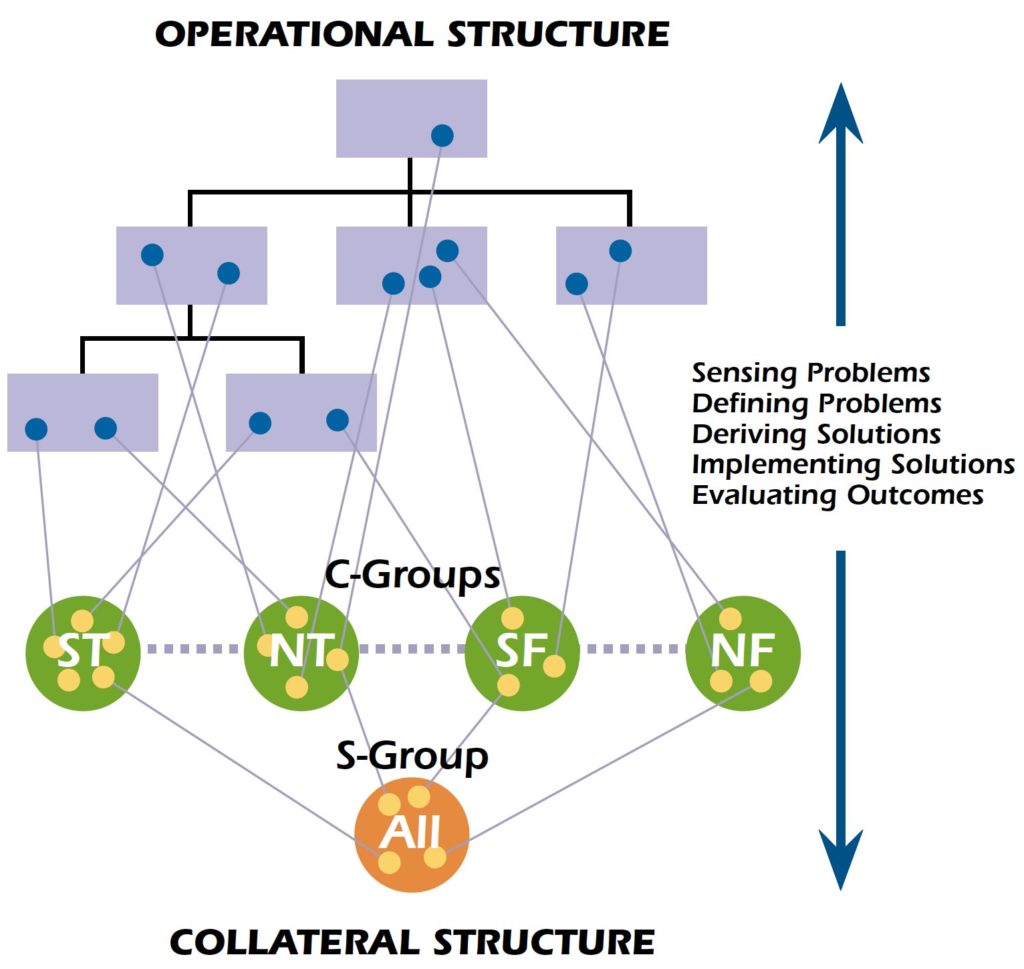

Zand [33] has suggested such an approach to organization-wide problem solving, referred to as the “collateral organization.” Zand considers the day-to-day, operational design as dealing with authority-production type problems while a parallel design concentrates on the ill-defined, long-term, system-wide type problems. The members in the collateral design would spend approximately 2–10 hours per week working on such complex problems; the remainder of their time would be spent back in the operational design. Figure 1 shows the separateness as well as the linkages between the traditional (operational) and the collateral design.

Figure 1

The Collateral Organization

A major reason for utilizing a parallel structure with overlapping membership is to increase the likelihood that creative and innovative ideas to problems can and will be implemented in the operational design. The trouble with assigning complex issues to staff groups, as is the customary practice, is that these groups are: (1) remote from the source of the problems and (2) not in any position of line authority to implement their own recommendations.

A collateral organization, in contrast, encourages members and line managers from the operational design to develop creative yet feasible solutions in a more relaxed, fluid, collateral design—and then enables them to return to the operational design and implement their solution from a formal position of authority in the organization. This ongoing cycle of sensing the problem (from the operational design), defining the problem and deriving solutions (in the collateral design), and implementing the solution (back in the operational design), is the foundation of the collateral organization. In addition, the collateral design forms groups of people that cut across the formal departments in the operational design so that a wide array of expertise and information is available in each collateral group. It is less likely, consequently, that important aspects of a problem will be overlooked or treated in a narrow way (as would be done if ill-structured problems were approached by one functional department in the operational design).

In Figure 1, the term C-Groups stands for either Collateral Groups or Conclusion Groups. Forming these C-Groups to be as different as possible from one another (as discussed below) helps ensure that all the underlying differences of any complex problem will be brought into the open for an active debate. The term S-Group stands for Steering Group or Synthesis Group, which is composed of one or two representatives from each C-Group. The mission of the S-Group is to address and then resolve the differences among the C-Groups (conveniently labeled as ST, NT, SF, and NF) and thus to achieve a far-reaching—effective—synthesis for all concerned.

DISTINGUISHING DUAL DESIGNS

It is important to distinguish the collateral organization from other design efforts that also create a dual or overlapping structural arrangement. For example, task forces, committees, project teams, and project management are not considered to fall under the heading of collateral organization since these second-order designs are oriented to a well-defined problem in an “authority-production” type atmosphere. For example, a special task force may be created to study the purchase and renovation of a new building; a project team is created to design and build a prototype labor-saving device; a project management design is developed to devote attention to the marketing of a new line of products for the firm. In general, these dual-design arrangements do not involve a distinction in well-defined vs. ill-defined problems as much as a way of giving special attention to new products, production methods, or facilities development, etc. Stated differently, these dual designs tend to focus on a problem that suggests quite clearly the necessary expertise needed to solve the problem—often a very narrow range of technical expertise. For an ill-defined problem, in contrast, it is not always clear what expertise is needed. (A further discussion of these dual designs can be found in [4].)

Another design approach which is first seems to resemble the collateral organization is matrix organization. Matrix has been defined in numerous ways in the literature. Gibson et al. [8] report that terms such as grid structure, multidimensional structure, global matrix, program management, and project management have been used interchangeably with matrix organization. Davis and Lawrence [7], providing the most comprehensive discussion on matrix to date, define the term by the existence of the two-boss model—where some people are reporting simultaneously to two superiors, one in the functional design and one in the matrix (business) team. Consequently, if any design were established whereby members would report exclusively to their project manager during the course of the project, this arrangement would not be viewed as matrix. Likewise, any task-force mission that has members working full-time on the task force, reporting to one boss, would not fit the Davis and Lawrence definition of matrix.

A collateral organization has some similarity to the matrix as far as the dual reporting relationship is concerned, with two important exceptions. First, it is possible that several members in the collateral design could have the same boss as in the operational design. Basically, the collateral organization does not establish the equivalent of the business team manager—one who manages the matrix team but does not have a formal position in the functional design. In essence, the persons who manage the groups in the collateral design are also managers in the operational (functional) design. Only those members who come from different departments than their collateral-design manager would have two bosses.

The second exception to the similarities between a matrix and collateral organization involves a critical difference in focus. In most cases, the matrix teams are oriented to solving “authority-production” type problems, just as the functional organization. Matrix organization combines a diversity of expertise within the matrix teams whereas the functional design has its specialized expertise divided into different functional departments. The collateral design, as mentioned earlier, is focused on defining and solving long-term, complex, and ill-defined problems, not authority-production type problems.

Another approach to problem solving in groups that bears resemblance to collateral organizations is QWL (Quality of Work Life) programs. Problem-solving groups are established collateral to existing union/management relationships to solve design, planning, and performance problems at the workplace [5]. The various groups are composed of representatives from different parts of the operational design that have some stake in the problem at hand. While these problem-solving groups typically concentrate on rather well-defined work problems, there are examples of using the union/management, cross-membership effort for more ill-defined problems. For example, Davis and Sullivan [6] report on a joint effort by union and management to design a new chemical plant for Shell Canada, Ltd. The problem-solving groups designed not only the overall structure of the new organization, but also the jobs, the reward system, and the various control mechanisms. In most cases, however, the creation of “production-oriented” groups—as QWL approaches, as the earlier Scanlon Plan [15], or as the “new” concept of quality control circles from Japan [25]—are centered on well-defined production problems, not ill-defined problems as is intended for the collateral organization.

EXAMPLES OF COLLATERAL DESIGNS

While the concept of collateral organizations is still rather new, it is possible to suggest some missions that would be suited especially well to this problem-solving approach. It has been observed, for example, that strategic planning does not take place well when restricted to the formal (often bureaucratic) design categories on the organization chart [22]. Also, since strategic planning has a bearing on the whole organization, not to mention its long-time frame, a separate collateral design that is special to strategic planning is suggested (rather than attempting to redesign the formal, operational design to make it more responsive overall to such long-term, complex considerations). The same has been discovered for any type of long-term problem focus such as monitoring a complex, multinational environment [12], where a collateral “intelligence” gathering system can be designed; or such as designing an organization wide, management-information system (MIS) to facilitate and support middle and upper management decision making [24]. The problem of R&D (Research and Development) units not providing usable new ideas and products can be approached, for example, by designing a collateral, knowledge-utilization design [11]. In this way, many organizational members would have the dual role of knowledge developers (in the collateral design) and knowledge users (in the formal, operational design) rather than having a separate group of R&D persons, which does not interface well with the rest of the organization [32].

Other such missions and special purposes might also be approached more effectively with a collateral organization. The question becomes: how to create a collateral design so that its potential for managing complex problem is realized? The focus now turns to suggesting a sequence of key steps to consider in designing collateral organizations. These generic steps are based not only on a logical flow of design decisions, but on some of the scientific principles that have been offered for designing effective organizations in general [1, 13].

CREATING COLLATERAL DESIGNS

Table 1 outlines the 10 basic steps involved in forming an effective collateral organization, based on the research in the field of organization design.

Table 1:

The Ten Steps for Designing Collateral Organizations

- Recognizing that a special-purpose, collateral design is needed to supplement the operational design for important, long-term, complex missions.

- Formulating the special-purpose or mission for which a collateral organization will be designed.

- Specifying objectives that the collateral design will attempt to achieve (5–15 objectives).

- Specifying tasks that need to be performed in order to achieve each specified objective (30–100 tasks).

- Identifying people who have the necessary abilities, skills, interests, knowledge and experience to perform the indicated tasks from any division in the organization (10–50 people).

- Determining the interdependencies between all pairs of tasks, anticipating how people would be working on these tasks in order to achieve the objectives.

- Forming boundaries around “clusters” of tasks denoting each collateral subunit, according to the principle of containing first reciprocal, then sequential, then pooled interdependencies within as opposed to between subunits.

- Designing the internal-structural characteristics of each collateral subunit, according to the principle of differentiation (i.e., norms, policies, and guidelines to fit with each subunit’s task environment).

- Designing the mechanisms to coordinate all collateral subunits together into a functioning whole, according to the principle of integration as well as to coordinate flows between the operational and collateral designs.

- Implementing, monitoring, and evaluating the new collateral design as the mission is being pursued.

Each step is discussed below, noting the relevant literature where appropriate.

Step 1: Recognizing Complexity

Step 1 emphasizes that organizational members or managers must realize that a particular problem or project will be most difficult to address in the formal, operational design [33]. Such a problem or mission would involve several if not many subunits in the formal organization, requiring their frequent or constant interaction. Unless the organization is very flexible, loose, and has been very supportive and rewarding of such interdepartmental interactions, it is unlikely that any creative, effective interchange will develop across these formal units.

Perhaps it should be re-emphasized that departments are oriented primarily to day-to-day concerns and are designed so that they do not have to interact much with other departments. In fact, reward systems of most complex organizations tend to reinforce departmental goals and objectives, event to the detriment of overall organizational goals and objectives [27, 29].

Step 2: Formulating the Mission

With the recognition that some special-purpose, collateral design is needed, Step 2 requires that organizational members specify the primary mission or purpose of the collateral design. Possible missions might include: strategic planning, identifying and solving complex problems that have not been managed well previously, developing an organization-wide, information system to aid in the decision-making process of middle managers, planning organizational changes and then guiding the implementation of these changes, evaluating organizational policies, enhancing the organization’s responsiveness to its environment, anticipating and monitoring environmental changes, and so on. One might envision a collateral design that would first set priorities on the several possible missions. Thus, determining the long-run strategy of the firm might precede efforts to evaluate organizational policies or design an organization-wide, information system (that presumes a clear strategy for the organization).

It is recommended, therefore, that an organization does not “jump” into creating one or more collateral designs until the relative importance and priorities of these missions have been established. The organization has to be aware, then, of the Type III error: the probability of solving the wrong problem versus the right problem, or solving the less important versus the most important problems given the limited resources of the organization [9, 23]. The opposite is to create a new collateral design for many or most “unresolved issues” and thus overwhelm members with many task force or committee assignments. Rather, the idea is to use collateral designs for what they are intended—the most important, complex undertakings of the organization, which usually have a critical impact on the future of the organization.

The procedure for establishing the importance and priority of several possible missions can be done through an initial collateral design, as noted above, or through an active debate among top management personnel. The judicial-decision process discussed by Wirt [31] or any version of the Hegelian dialectic [2] would be useful in this regard. Perhaps a debate on the underlying assumptions that argue for each proposed mission would help management crystallize their priorities [21].

Step 3: Specifying Objectives

Once the overall mission for the collateral design has been chosen, Step 3 asks managers to specify, in as much detail as possible, the particular objectives that the collateral design would be designed to achieve. Some possibilities might be: a specific plan or report from the collateral design, a statement or outline of the major problems facing the organization over the next ten years (including priorities), a detailed design of a management-information system, an assessment of R&D’s role in corporate planning, detailing implications regarding human-resource changes in the organization, and so on. In most cases, a complex mission can be subdivided into five to fifteen sub-missions or objectives, indicating the several outcomes expected from the collateral design.

This step involving objectives is somewhat analogous to what generally was intended with “Management-By-Objectives” or MBO [26]. That is, before an organization engages in any activity, it should be clear about the final outcomes or objectives, and then work backwards to consider the tasks, resources, designs, etc., in order to accomplish these objectives. Specifying objectives at an earlier stage (no matter how tentative for the moment) does not leave members in the collateral design wondering why they were assembled and what it is they really are to do. Surprisingly, committees and task forces often are created to solve a problem that has not been prioritized yet and, in addition, members are not at all clear on what final outcome is expected from them.

Step 4: Specifying Tasks

After a listing has been made of the several objectives pertaining to the identified mission of the collateral design, Step 4 requires the top managers to indicate the specific tasks that need to be done in order to accomplish the stated objectives. That is, what work has to be done, what information has to be collected, what resources need to be acquired, what decisions have to be made, what actions have to be taken—in order to maximize the probability that the specific objectives, and hence the overall mission, will be achieved. It might be said that one reason for first translating the mission into objectives is to facilitate the listing of specific tasks, which is expected to be easier than going from the mission directly to these tasks.

Any complex mission involving five to fifteen separate objectives is likely to result in anywhere from 30 to 100 tasks. More than 100 tasks generally gets the design process bogged down with too much detail. Some tasks might be as follows: conducting a market survey of consumer interest in this product, asking potential users their opinions on the design of the management-information system, performing the relevant statistical analyses on the survey data, monitoring the pricing changes of our major competitors, deciding on the key parameters in the forecasting model, communicating the results of the final report to the relevant external agencies, defining the role of corporate planners regarding the formulation of research projects, taking account of the organization’s culture and climate in preparing a plan for implementing a new reward/incentive system, and so on.

It is important to emphasize that both the list of objectives and the list of tasks should be viewed as comprehensive and complete by a number of top managers responsible for creating the collateral design. This requires that both lists be reviewed a number of times to assure completeness and to guarantee that redundancies, inconsistencies, and jargon have been removed.

Step 5: Identifying People

Step 5 concerns the human-resource aspect of the collateral design. Specifically, given the objectives and tasks, who are the best people to staff the new design, how many are needed, what are their characteristics and areas of expertise, and where in the operational design are they now located. It is only by having the objectives and tasks fairly well specified that one can begin to answer these questions. Naturally, one can always add people to the collateral design as needed, but for efficiency sake and for the sake of developing cohesive, effective teams in the new design, it is helpful to have planned for the human-resource question well in advance of implementing the collateral organization.

Since, by definition, the missions involve issues that cut across a number of existing organizational departments or subunits, members for the new design would involve people from different parts of the organization. It may even be appropriate, at times, to hire persons from outside of the organization on a temporary basis in order to supply important areas of expertise to the collateral design—expertise that may not be represented in the organization. Outside “consultants” can be utilized in this manner. Regardless, it seems evident that whatever the tasks and objectives are, the necessary and relevant areas of expertise, information, knowledge, and experience should be included in the pool of human resources for the mission in question.

Thus far, the missions, objectives, tasks, and people for the collateral design have been identified. What is needed now is to consider forming these “elements” into a particular collateral design; arrangements into subunits. Only if the necessary people for the mission numbered less than ten, would it be feasible to have just one group for the collateral design, similar to a single committee or task force. In most complex, large corporations, the mission may break down into 10 objectives, 60 tasks, and 40 people. This is not an uncommon scope for a mission that is absolutely critical to the long-term survival of the organizations, impacts on most or all major divisions in the operational design, and requires, therefore, a broad base of expertise and representation from all these segments in the organization. But this is precisely why a collateral design is needed and why prior efforts of managing the mission (in the operational design alone) simply have not worked. The next steps of the process draw on organization-design knowledge that provides principles and criteria for subdividing the total set of objectives, tasks, and people into manageable subunits—while also providing “integrators” and mechanisms to coordinate the subunits into a functioning whole.

Steps 6 & 7: Determining Task Interdependencies and Forming Subunit Boundaries

Step 6 is perhaps the most difficult and complex part of the design process: to determine (anticipate) all the task interrelationships (interdependencies) that will exist as people begin working on tasks in pursuit of objectives. Only by knowing the nature and strength of the interdependency for each likely pair of tasks, will it be possible to conduct the following step properly: that of determining the way in which the total set of objectives, tasks, and people most optimally divide into separate, manageable subunits.

Thompson’s [30] concept of task interdependencies is very helpful here. Specifically, Thompson defines three types of interdependencies that can take place either within or between organizational subunits: pooled, sequential, and reciprocal. Pooled interdependence is when two or more tasks can be performed relatively independent of one another, and in order to obtain certain outcomes or objectives, the separate outputs of each activity can be combined or pooled together at some later time. With pooled interdependence, therefore, there is not much need to coordinate, plan, schedule, or communicate with respect to the separate tasks before the “pooling” act is performed, and even then, the combining is rather straightforward and can be done according to standardized procedures.

Sequential interdependencies, however, require that in order for the final outcome or end-product to be achieved, the separate tasks and activities must be combined in a certain sequence. Thus, task A is performed first, then B, then C which then results in the completion of an overall outcome which, consequently, requires a certain amount of planning and scheduling across several tasks in order to foster efficiency and effectiveness.

Finally, reciprocal interdependencies occur when a constant or frequent cycling of interaction and input-output relationships takes place between various tasks so that a “final” outcome can be achieved. For example, persons performing task A must constantly interact with those performing tasks B and C for the outcome to be realized. Fostering and managing such ongoing and potentially complex interaction patterns among reciprocal-interdependent tasks, not surprisingly, requires additional coordinating mechanisms beyond procedures, plans, and schedules.

The three types of interdependencies, as implied above, have different costs associated with coordinating tasks in order to achieve a desirable outcome. Specifically, pooled interdependencies are least costly to coordinate because only procedures may have to be instituted at one point in time. Sequential interdependencies are more costly to coordinate due to the planning and scheduling which must take place before and during the performance of the tasks. Reciprocal interdependencies are the most costly since coordination requires constant monitoring, communication, and “mutual adjustment” [30].

For the purpose of minimizing the costs of coordinating various tasks, the most costly forms of interdependencies should be placed within as opposed to between subunit boundaries [30]. Specifically, as much as possible the boundaries of subunits first should contain most or all identified reciprocal interdependencies, then the sequential interdependencies, and finally, the pooled interdependencies can be left between subunit boundaries. In most “real” settings, however, some sequential and even a few reciprocal interdependencies would be left between subunits since it may be quite impossible to come up with one set of subunit boundaries that contain all interdependencies, perfectly.

Step 6 and Step 7 entail identifying all the two-way interdependencies among all the listed tasks so that an “optimal” design of subunit boundaries can be created for the collateral organization. In addition, these boundaries can be shown not just as the subset of tasks that each subunit is responsible for addressing, but indicating the subset of people who are assigned to work on these tasks, also showing the subset of objectives that the people in each subunit are attempting to accomplish. Thus, a subset of people working on a subset of assigned tasks according to a subset of objectives (as a subset of the total identified mission), constitutes the definition of each subunit in the collateral design. The concept of task interdependencies provides the basis for subdividing tasks, people, and objectives into “optimal” subunits.

A number of techniques are available for determining task interdependencies and then forming the subunits for a collateral design. For example, the “Q-Sort technique” can be utilized by having managers first list each task on a separate 3 X 5 card and then sort the cards into piles representing similar, overlapping, interdependent tasks [28]. This requires considerable judgment but can be accomplished effectively for small collateral designs (e.g. less than 50 tasks). A variant of this method is suggested by Mackenzie [19, 20] in his design technology referred to as “Organizational Audit and Analysis.” The “socio-technical systems” approach [3] also requires intuition and judgment in forming groups by examining task flows and tasks interdependencies. Kilmann [10] offers a statistical approach by suggesting the use of correlational and factor analyses from questionnaire data on respondents’ perceptions of task requirements. Using this “MAPS Design Technology,” a statistical analysis enables a larger set of tasks to be sorted into subunits via computer programs (e.g., 50–150 tasks). Unfortunately, no comparative, empirical study has been done that examines the relative costs and benefits of using these different methodologies for forming collateral designs. (See [20] for a theoretical critique of these different design methods.)

Step 8: Subunit Differentiation

Step 8 involves designing the internal-structural characteristics of each subunit in the collateral design, once the subunit boundaries have been determined during the preceding step. The concept of “differentiation” developed by Lawrence and Lorsch [14] is relevant to this step of the process.

Differentiation as a design criterion suggests that given a particular set of design categories or subunits of an organization (i.e., given the specification of subunit boundaries), each subunit should be internally designed to best fit with the characteristics of its task environment. For example, if the task environment or sub-environment facing a subunit is primarily stable, then a highly-structured, traditional, bureaucratic design would best foster subunit efficiency and effectiveness (e.g., as in most production departments). At the same time, if the members in the subunit are motivated and prefer to work in such a bureaucratic design (because of various motivational and personality characteristics), then the efficiency and effectiveness of the subunit is further enhanced because of this “fit” [18].

On the other hand, if the task environment facing the subunit is dynamic and changing, then a more loosely-structured, nontraditional, organic-adaptive design would be best [1] (e.g., as in some R&D departments). In the latter case, individuals who are motivated and prefer to work in such a fluid design would best contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of the subunit, given the necessary expertise, etc. It is important to emphasize, however, that the extent to which the various subunits face different environments is the extent that the internal designs of the subunits would be different, ranging from the “pure” bureaucratic to an extreme organic-adaptive design (as well as suggesting the different types of individuals who are best to staff the various subunits).

Since a collateral organization faces a dynamic, complex and ill-defined task environment, the internal structure of subunits should be organic-adaptive. The internal characteristics of the operational design should be bureaucratic (consistent with the authority-production forms). Only if the operational design contained subunits that faced a dynamic environment (as in R&D departments) would any subunits in the operational design have an organic-adaptive structure. In fact one might expect that most of the operational design would be bureaucratic (specific rules and procedures, a clear line of authority, well-defined job positions and responsibilities, etc.), and therefore the design of the collateral organization would be very different than what members are accustomed to in the operational design.

This creates a special problem for designing collateral organizations. The members must recognize that the structure of the operational design and the collateral design need to be quite different, and the members must be able to operate in these two different “cultures” as they go back and forth between the two designs. The worst case would be if the collateral design were created with the same type of bureaucratic structure that is found in most operational designs, as a result of familiarity and custom. In this case, by not applying the principles of differentiation, as discussed above, the collateral design would be attempting to define and solve very complex problems within a rigidly defined set of rules, procedures, hierarchy, and job specifications. Besides, it would be a wasted effort to attempt to anticipate all the rules and regulations that are necessary for effective behavior when the task environment of a collateral subunit is so complex and changing, requiring frequent changes in behavior (and thus requiring frequent changes in rules and procedures). Only if one or more subunits in the collateral designs were involved with routine tasks (such as information collection and statistical analysis, for example), would a more bureaucratic type structure be appropriate (for those particular subunits).

With an organic-adaptive design in mind, Step 8 would entail the development of norms, general policies, and guidelines on how each group will proceed. The leadership activities would tend to be more shared than hierarchical in nature, and the influence processes would be based more on expertise, information, persuasiveness, and relevance rather than legitimate power and authority (i.e., personal power vs. positional power). Perhaps the best way of describing the structure and functioning of a collateral subunit (as an organic-adaptive system) is according to professional norms and colleagueship [1].

Step 9: Subunit Integration

Step 9—how to design the mechanisms to coordinate the residual interdependencies between subunits—is handled by the concept of integration [14, 17]. It is recognized that even if most of the interdependencies are contained within subunit boundaries, the subunits themselves are still not entirely independent of one another. At a minimum, certain pooled interdependencies would remain, and more often than not, some sequential and even reciprocal independencies would still be present in any complex organization. Integration is concerned with coordinating the subunits into a functional whole. Often the use of a “loose” management hierarchy would constitute the primary form of integration across collateral groups (i.e., managers being responsible for coordinating the interdependencies of two or more groups). Other integration mechanisms include the “informal” organization, overlapping group memberships, as in Likert’s [16] linking pin, and specially designed information links. Further, the individuals performing the integrating roles should be ones that appreciate if not possess the variety of skills, styles, goals, etc., that exist within the several groups being coordinated.

An important issue of integration, however, is not so much coordinating the activities across the various collateral groups, but the coordination of activities between the collateral design and the operational design. Since the internal structure of these dual designs would be quite different, there is a special problem involved in moving (managing) people across these two different systems. Members involved in both designs must learn to function in two different ways and not be confused by the switch from one culture to another. Furthermore, some integration mechanism should be established to assure that only the ill-defined problems get presented to the collateral design rather than bringing them “everything” from the operational design. In addition, integration in this context requires mechanisms to bring solutions from the collateral design back to the operational design in a well-conceived plan of implementation. Managing this back-and-forth flow of problems, people, information, solutions, and results, necessitates a unique blend of “integrators” (as persons) and creative linkages in terms of mechanisms, functions, and incentives.

Step 10: Implementation and Evaluation

The final step in the design process, Step 10, involves: (1) implementing the collateral organization as designed in the previous nine steps, (2) monitoring and adapting its design as experience in the collateral organization grows, and (3) evaluating how well the collateral design and the design process have fostered the attainment of the stated mission.

In essence, Step 10 puts the collateral organization into action. But an important aspect of this activity is to adjust and modify the design as management and members learn about such organized efforts. There are always unexpected problems that emerge, some of which have to do with members having two positions in the organization—one in the operational design and one in the collateral design. There may also be pressures for members to spend more time in both designs, which are rarely feasible. These sorts of problems have to be worked out in order for both designs to perform as intended.

Step 10 also involves evaluating the results of the design effort, which is especially important if the organization wants to use collateral designs in the future and, therefore, wants to learn from its experiences. Further, top management should be interested to learn if the mission was accomplished successfully and what role the collateral design had in the final outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

It is up to the imagination of organizations and designers to develop numerous uses of collateral, special-purpose designs. This paper has mentioned only a few, but certainly this list extends way beyond these and definitely beyond the single concept of a committee system.

On the other hand, I am not advocating that an organization forms an additional collateral design every time some new problem or purpose emerges. Eventually, members would be confused by such multi-designed organizations (e.g., having membership in four or five collateral designs) and this would approach the feeling of constantly moving from one committee to another as a way of avoiding the real and important issues. It might be argued, therefore, that an organization that finds itself in a very dynamic and changing environment, where new problems and purposes emerge frequently, could have a collateral design concentrating on the initial but critical purpose of problem sorting, problem formulation, problem finding, and the like. Such a “problem management” design [9] would be a perpetual collateral design (obviously with a very broad range of expertise and wide representation throughout the organization) that would resolve some problems and then go on to others [1].

The ultimate test of the ideas and suggestions in this paper remains an empirical question. While I doubt the feasibility of conducting tight, laboratory experiments as a way of examining these complex design issues, it might be possible to conduct some field studies. For example, if several organizations would be interested in the general topic of complex problem solving, maybe they would be willing to establish several different efforts; perhaps several different types of collateral designs vs. approaching complex problems through staff groups or via traditional operational departments. Although alternative explanations for any findings would be numerous, carefully following and monitoring the processes and outcomes of these various efforts over time could be quite illuminating. Some qualitative or even quantitative assessments could be made that might help develop further knowledge and insights. Certainly, developing this sort of knowledge base is extremely relevant to offering organizations some guidelines and prescriptions for managing increasingly complex problems.

REFERENCES

[1] W. G. Bennis, Changing Organizations (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1966).

[2] C. W. Churchman, The Design of Inquiring Systems (Basic Books, New York, 1971).

[3] P. A. Clark, Organizational Design: Theory and Practice (Tavistock, London, 1972).

[4] D. I. Cleland and W. R. King, Systems Analysis and Project Management (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1968).

[5] L. Davis, “Enhancing the quality of working life: developments in the United States,” International Labour Review, 116 (1977), 53-65.

[6] L. Davis, and C. Sullivan, “A labor-management contract and quality of working life,” Journal of Occupational Behavior, 1 (1975).

[7] S. M. Davis and P. R. Lawrence, Matrix (Addison-Wesley, Reading MA, 1977).

[8] J. L. Gibson, J. M. Ivancevich, and H. H. Donnelly, Jr., Organizations: Structure, Processes, Behavior (Business Publications, Dallas, 1973).

[10] R. H. Kilmann, Social Systems Design: Normative Theory and the MAPS Design Technology (Elsevier North-Holland, New York, 1977).

[11] R. H. Kilmann, “Organization design for knowledge utilization,” Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization, 3 (1981), 211-231.

[12] R. H. Kilmann and K. Ghymn, “The MAPS design technology: designing strategic intelligence systems for multinational corporations,” Columbia Journal of World Business, 11 (1976), 35-47.

[13] R. H. Kilmann, L. R. Pondy, and D. P. Slevin, The Management of Organization Design: Volumes I and II (Elsevier North-Holland, New York, 1976).

[14] P. R. Lawrence and J. W. Lorsch, Organization and Environment (Harvard University Press, Boston, 1967).

[15] E. G. Lesieur and E. S. Puckett, “The Scallion plan has proved itself,” Harvard Business Review, 47 (1969), 109-118.

[16] R. Likert, New Patterns of Management (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1961).

[17] J. W. Lorsch and P. R. Lawrence, Studies in Organization Design (Irwin-Dorsey, Homewood IL, 1970).

[18] J. W. Lorsch and J. J. Morse, Organizations and Their Members (Harper and Row, New York, 1974).

[19] K. D. Mackenzie, “A process-based measure for the degree of hierarchy in a group, III: applications to organizational design,” Journal of Enterprise Management, 1 (1978), 175-184.

[20] K. D. Mackenzie, “Concepts and measures in organizational development,” in: J. D. Hogan, Ed., Dimensions of Productivity Research, Vol. 1 (American Productivity Center, Houston, 1981), 233-304.

[21] R. O. Mason and I. I. Mitroff, Challenging Strategic Planning Assumptions (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1981).

[22] I. I. Mitroff, V. P. Barabba, and R. H. Kilmann, “The application of behavioral and philosophical technologies to strategic planning: a case study of a large federal agency,” Management Science, 24 (1977), 44-58.

[23] I. I. Mitroff and T. Featheringham, “On systematic problem solving and error of the third kind,” Behavioral Science, 19 (1974), 383-393.

[24] I. I. Mitroff, R. H. Kilmann, and V. P. Barabba, “Avoiding the design of management misinformation systems: a strategic approach,” in: G. Zaltman, Ed., Management Principles for Nonprofit Agencies and Organizations (American Management Association, New York, 1979), 401-429.

[25] W. G. Ouchi, Theory Z (Addison-Wesley, Reading MA, 1981).

[26] W. J. Reddin, Effective Management by Objectives (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1972).

[27] J. A. Seiler, “Diagnosing interdepartmental conflict,” Harvard Business Review, 41 (1963), 121-132.

[28] W. Stephenson, The Study of Behavior: Q-technique and Its Methodology (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1953).

[29] K. W. Thomas, “Conflict and conflict management,” in: M.D. Dunnette, Ed., The Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Rand McNally, Chicago, 1976), 889-935.

[30] J. D. Thompson, Organizations in Action (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1967).

[31] J. G. Wirt, A Proposed Methodology for Evaluating R&D Programs in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (The Rand Corporation, Santa Monica CA, 1973).

[32] G. Zaltman, “A discussion of the research utilization process,” in: G. Zaltman and R. Duncan, Eds., Strategies for Planned Change (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1977).

[33] D. E. Zand, “Collateral organization: a new change strategy,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 10 (1974), 63-89.