10 Apr Assumptional Analysis:

The Essence of Quantum Thinking

by Ralph H. Kilmann

This article is adapted from R. H. Kilmann, Quantum Organizations: A New Paradigm for Achieving Organizational Success and Personal Meaning (Newport Coast, CA: Kilmann Diagnostics, 2011), 121–135.

Assumptional analysis is a systematic method for tackling the most complex steps of problem management: defining problems and implementing solutions. This method not only pinpoints all the decision trees that are potentially relevant to problem definitions and implementation plans; it also probes below the surface of each tree to reveal its roots—the implicit assumptions that keep each tree alive and well. It is through the use of all the relevant areas of expertise from both inside and outside an organization that a synthesis of different decision trees and their roots can be developed—as members originate a new tree in their quantum forest. Using assumptional analysis is a superb illustration of quantum thinking: Both the right and left hemispheres of every participating mind/brain are actively involved in creating a new tree in the forest, providing altogether new categories and relationships for resolving a complex problem.

It must be stressed, however, that if a problem is defined incorrectly, all the subsequent steps of problem management are not only irrelevant but possibly harmful. Similarly, failing to implement the selected solution immediately invalidates all the previous steps and has its own frustrations and damaging consequences. It is therefore imperative that members take deliberate action to minimize the defining errors and implementing errors for the most important challenges facing their organization. Incidentally, sensing problems and evaluating outcomes are the least complex steps of problem management, since they require either “go” or “no go” decisions: Is there a significant gap that deserves our attention? The step of deriving solutions is not that complex either, since there are numerous cost/benefit methods for choosing among alternative solutions.

Assumptional analysis enables all members to develop self-aware consciousness about the validity of their proposed problem definitions and implementation plans. The basic premise is simple: Whenever someone concludes that his definition of the problem is correct, his arguments are valid only if their underlying assumptions are accurate. We define assumptions as all the things you have to take for granted as true (including human nature, mother nature, father time, and lady luck) in order to argue convincingly that the conclusion, as stated, is correct. Generally speaking, an initial conclusion is anything that is argued for or against: most often, a problem definition or implementation plan. These conclusions are termed initial since they will certainly undergo change as their underlying assumptions are analyzed and revised. Initial conclusions are just a way to initiate the process—a way of getting at the tried-and-true but potentially false (or uncertain) assumptions.

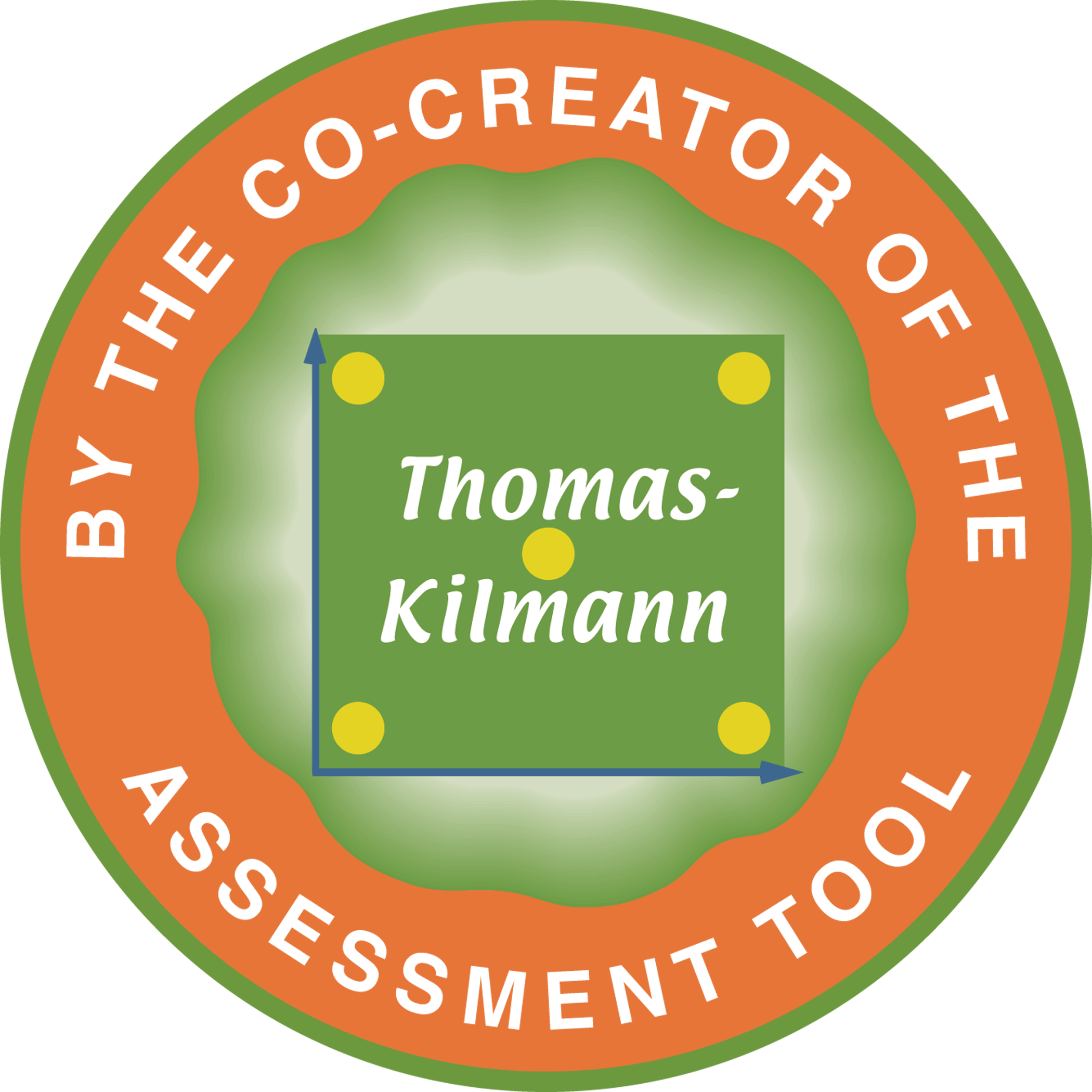

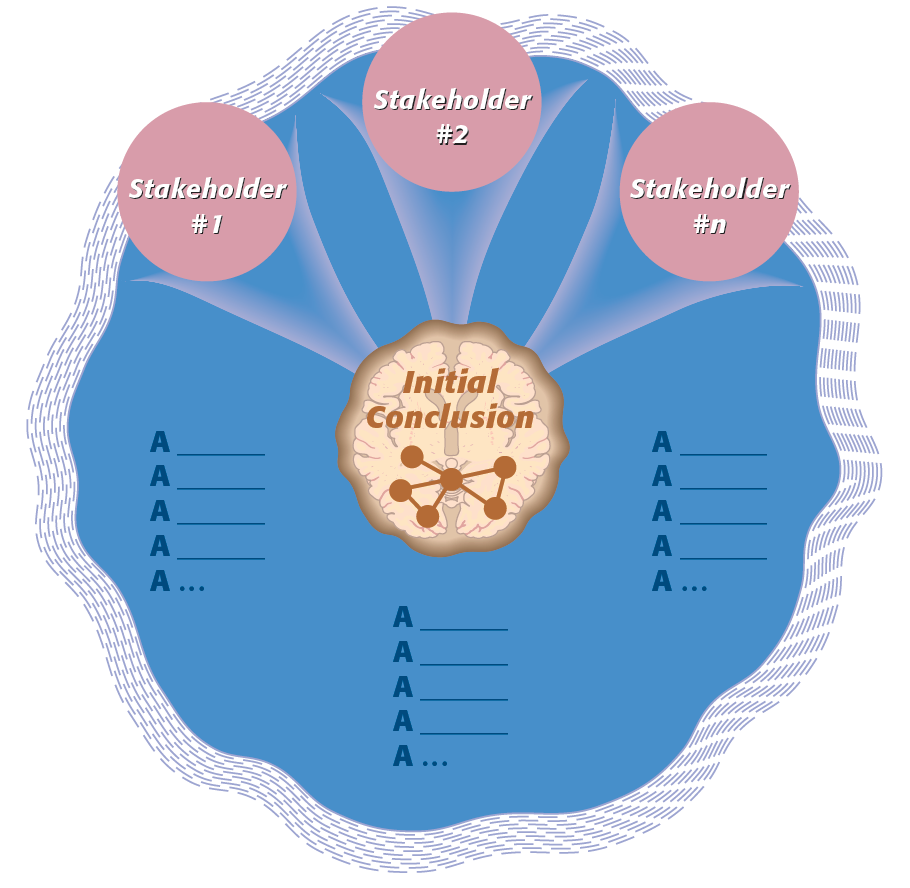

The assumptions underlying a conclusion can be surfaced by listing all the possible stakeholders—those inside and outside the organization—who are associated with the initial conclusion and therefore have a stake in what takes place. The essential reason for identifying stakeholders is not to list people for the sake of listing them, but to surface assumptions. The objective is not to miss any relevant individual, group, or organization. As represented in Figure 1, members make assumptions about what various stakeholders want, believe, expect, and value. Stated differently, any initial conclusion is a set of mental categories (and relationships) that implicitly assumes how stakeholders see, think, and behave.

Figure 1

Stakeholders for an Initial Conclusion

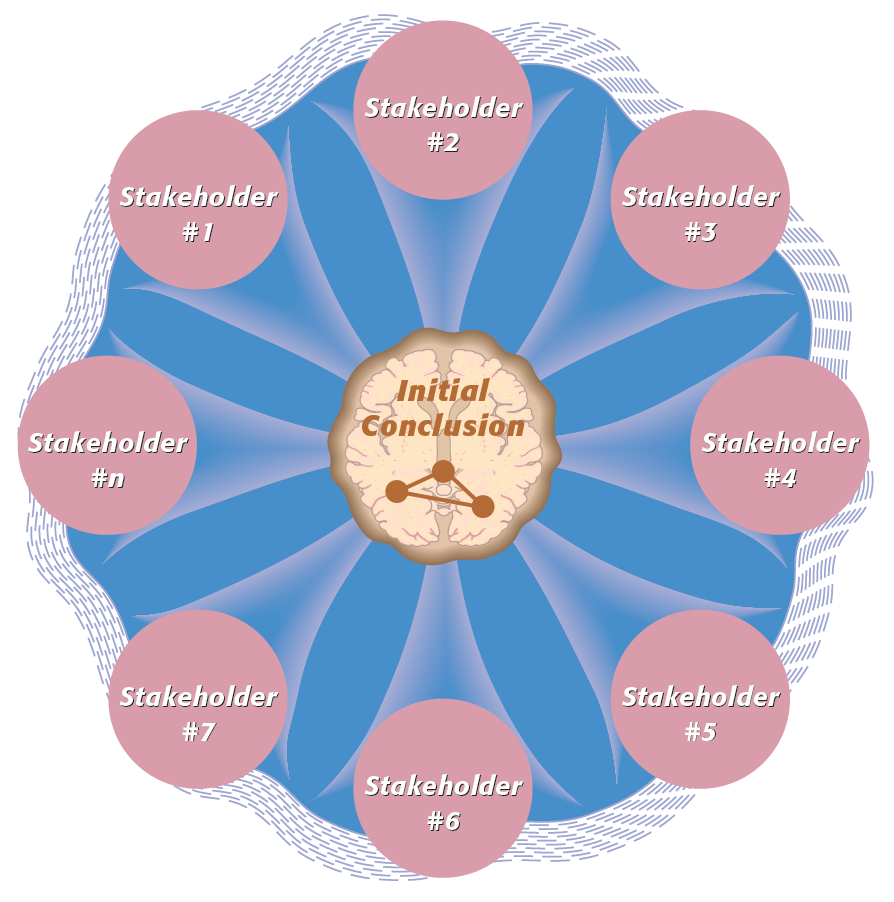

Figure 2 shows an initial conclusion concerning strategic change—surrounded by some of the typical stakeholders that would be affected by a change in strategic direction. Thereafter, these same stakeholders could also determine whether the strategic change will eventually be achieved. Thus, there is a two-way relationship between the initial conclusion and each potential stakeholder. Notice that each initial conclusion represents a schema/paradigm that views the problem from a limited perspective: as a single decision tree with branches. (Naturally, there are a number of other significant stakeholders besides those illustrated in eight circles here, such as other nations, future employees, family members, and best friends.)

Figure 2

Stakeholders for Strategic Change

For each stakeholder, members list their assumptions: What would have to be true about any and all aspects of a given stakeholder in order to argue, most convincingly, that the conclusion, as stated, is true? Indeed, each assumption is written in a form intended to maximize this support, despite how credible, obvious, or, instead, how ridiculous the assumption may appear. The “truth” of each assumption will be investigated later. As Figure 3 reveals, members can now see the implicit assumptions behind their initial conclusions. Just as with surfacing cultural norms, people may experience delight as they materialize the quantum waves that have been unconscious in their organization—and underneath their decision trees.

Figure 3

Surfacing Assumptions for Each Stakeholder

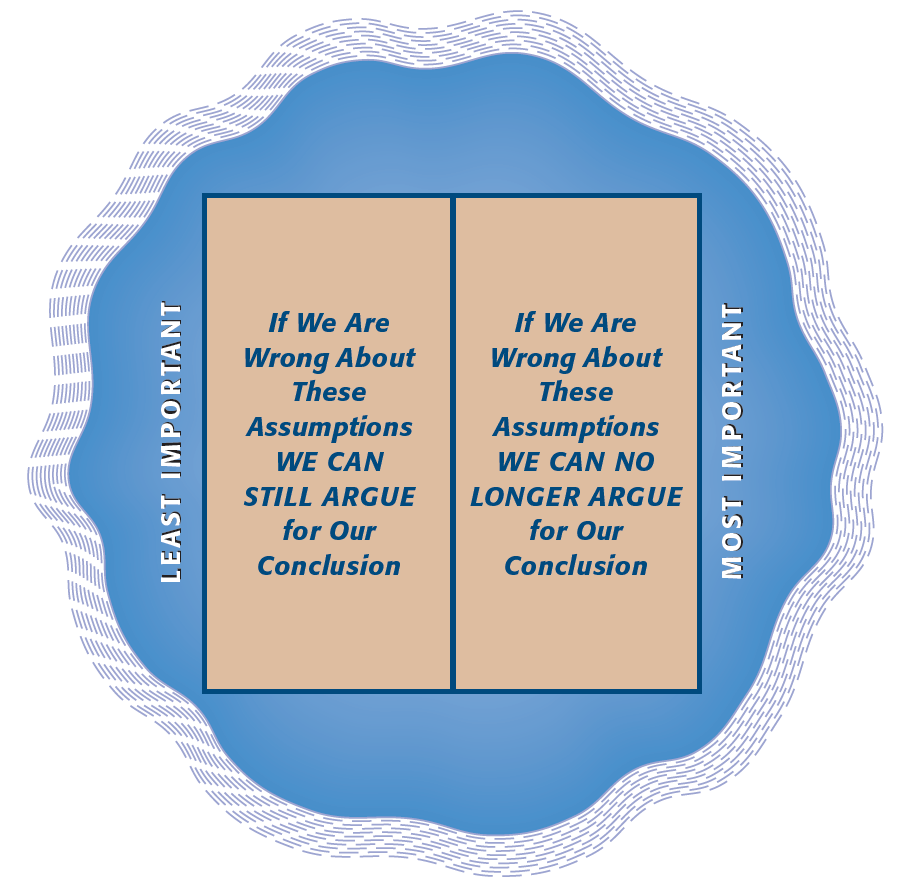

Now members must attempt to figure out the tens if not hundreds of implicit assumptions they have surfaced. Not surprisingly, we introduce several new categories for our minds/brains. First, are all assumptions of equal importance? There are always several least important assumptions that, even if they are false, do not prevent you from arguing forcefully for your conclusion. But there are ordinarily some most important assumptions that, if they turn out to be false, would greatly undermine your entire argument. In this case, you can no longer argue for the conclusion when the fallacy of such a basic assumption has been revealed. The distinction is shown in Figure 4 as a simplified either/or classification.

Figure 4

Distinguishing Assumptions by Their Importance

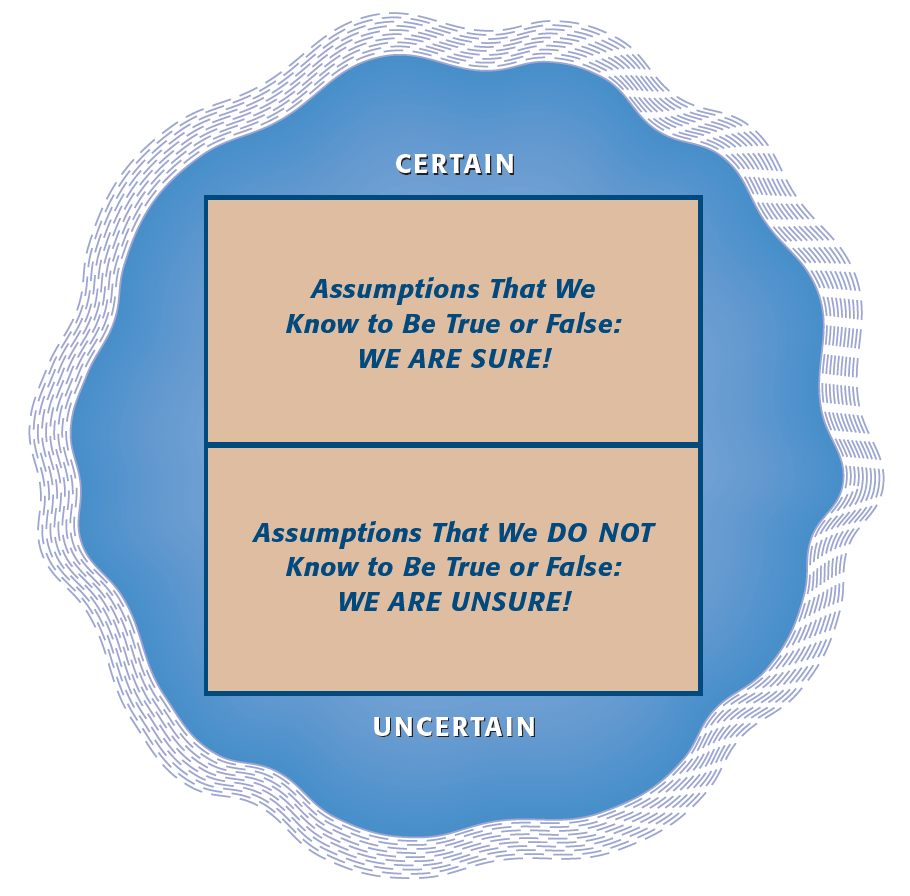

Here is an additional category for the mind/brain that helps people make sense of all their implicit assumptions: Are all assumptions of equal certainty? It seems that some assumptions are more certain (or uncertain) than others. On the one hand, a fact is an assumption that is expected to be true—or false—with complete certainty (100%). On the other hand, an assumption has great uncertainty when nobody can predict or control its eventual truth. In this situation, the certainty of the assumption is a 50/50 proposition: It is just as likely to be true as it is false. Figure 5 illustrates the certainty distinction: Here the top line is 100% certain and the bottom line is 50/50, while any assumption in the middle is 75% certain.

Figure 5

Distinguishing Assumptions by Their Certainty

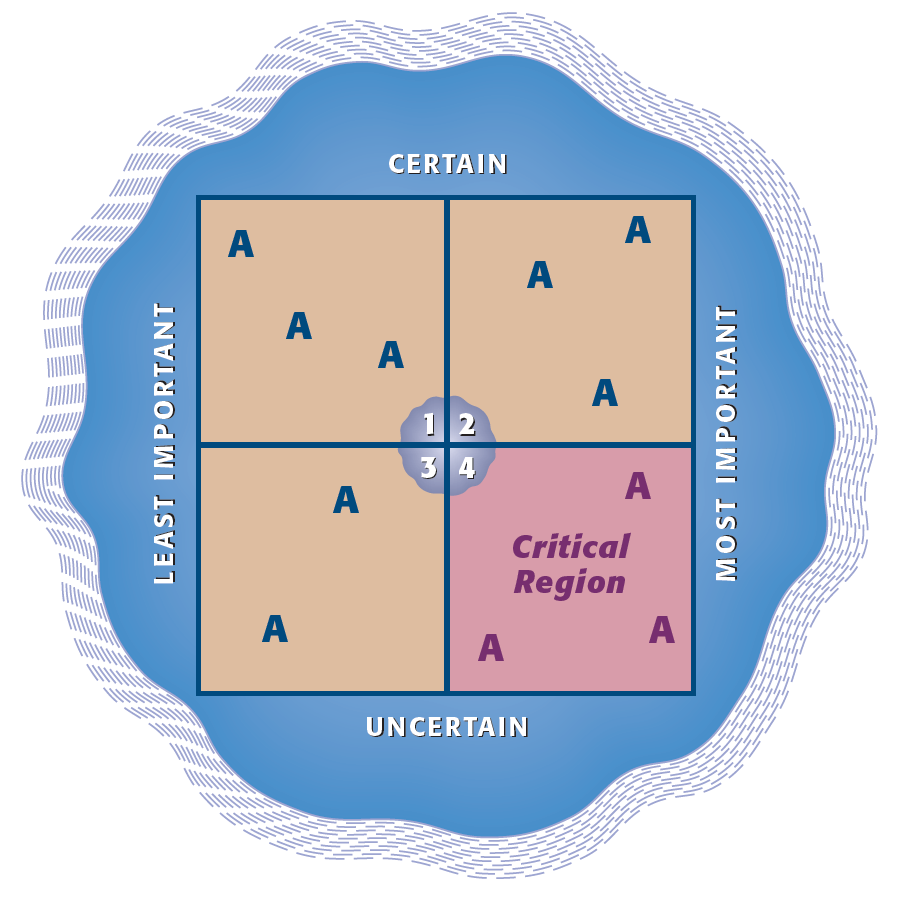

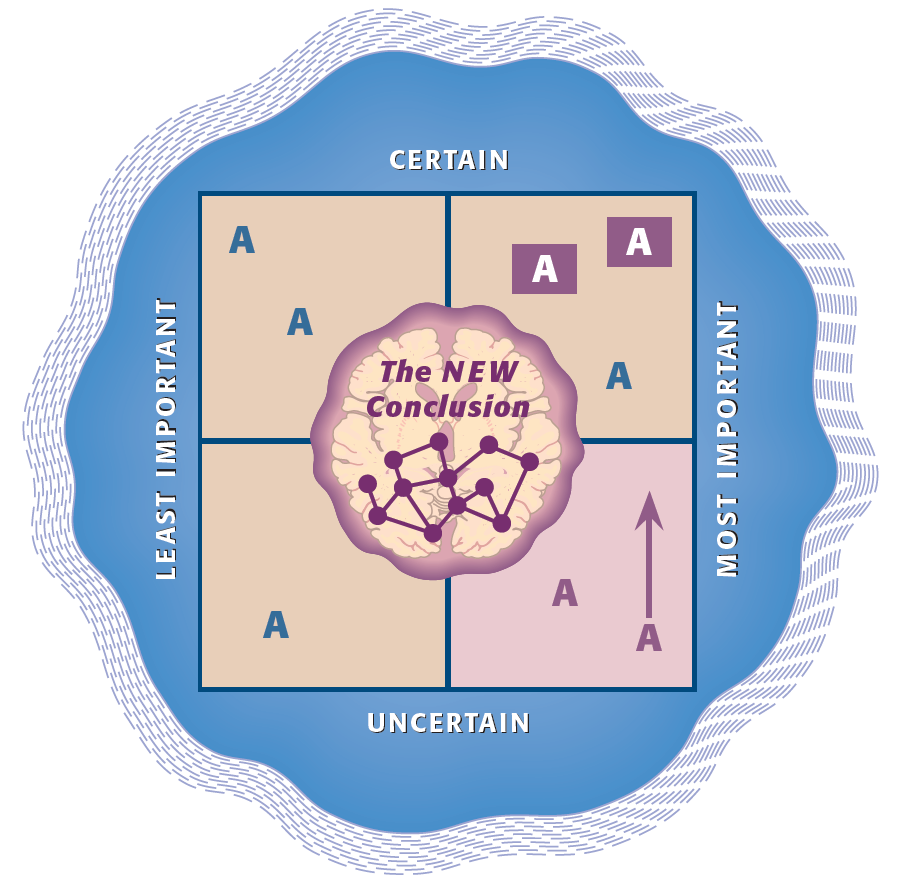

Figure 6 portrays the assumption matrix for classifying assumptions according to their importance to the initial conclusion and also according to their certainty. Is the assumption, practically speaking, most important to arguing for your conclusion or is it least important? Is the assumption, as stated, fairly certain to be true (or certain to be false), or is its truth (or falsity) uncertain? Combining the two distinctions creates four categories of assumptions: (1) certain, least important, (2) certain, most important, (3) uncertain, least important, (4) uncertain, most important. This assumption matrix enables members to untangle the roots behind all the trees in their quantum forest by explicitly classifying implicit assumptions.

Figure 6

The Assumption Matrix for Classifying Assumptions

The first category (certain/least important assumptions) represents trivia—highly certain facts that have little bearing on the subject at hand. The second category (certain/most important) represents important facts; if we know them to be true, these assumptions do not contribute anything new. In this second category, however, it might be astonishing to discover that some central assumptions behind our favorite conclusion—now that these assumptions have been surfaced for examination—are clearly false, when all along we were assuming exactly the opposite. The third category (uncertain/least important) shows what is not fully known to be true (or false), but these issues are not primary to the arguments being presented. The fourth category (uncertain/most important) emphasizes the principal reason for surfacing and classifying assumptions. This revealing category highlights assumptions that are most important to the initial conclusion (if you’re wrong about any of these assumptions, all your arguments fail), yet there is considerable uncertainty regarding the truth or falsity of these assumptions. As suggested earlier, maximum uncertainty presents a 50/50 split: These most important assumptions, as stated, are just as likely to be false as they are to be true.

The fourth category is named the critical region. This area is where the ultimate challenge to any argument will be focused. Too often, this critical region not only is neglected but is deliberately repressed. Individuals and groups arguing strongly for their conclusions do not want to expose their Achilles’ heel: Others would see the weakness of their arguments. In short, building a problem definition or implementation plan on assumptions in the critical region is like building a house on a foundation of quicksand.

The second category is very meaningful when it presents members with their biggest surprise ever: when one or more of the most important assumptions that support the initial conclusion are actually false without any doubt whatsoever. Yet people have been making decisions according to these false assumptions for a very long time. Only by having surfaced their implicit assumptions, however, are the members able to confront—face to face—the false assumptions that have guided how they see, think, and behave. But finally they have the opportunity to do something about it: They now can revise these false assumptions by writing them to reflect what they know is true and, thereby, augment their consciousness.

The emphasis of assumptional analysis next shifts to examining the assumptions that were classified into the two most important cells of the matrix (the right-hand side of Figure 6). Regarding the critical region, it is worthwhile to collect information from people, books, newspapers, and the Internet to discover the actual “truth” of these assumptions.

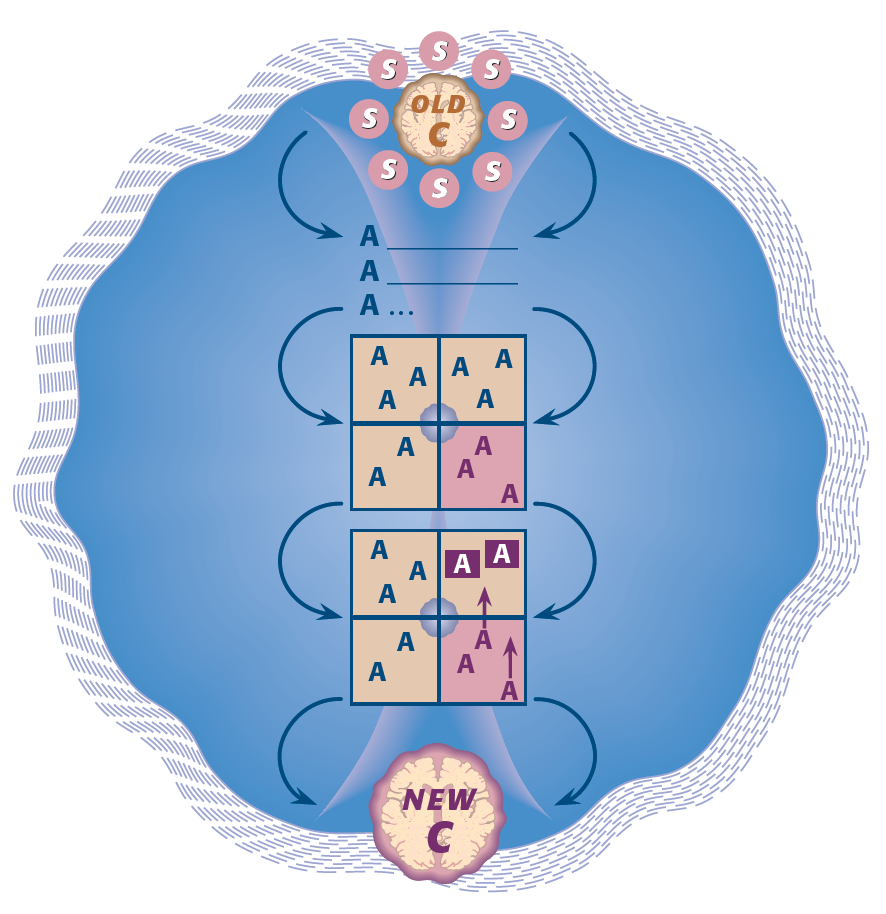

Figure 7 reveals how reversing assumptions that were known to be false into statements that are known to be true creates revisions in the assumption matrix [A]. Further, new information may transfer previously uncertain assumptions to the certain region, although these might have to be rewritten in order to assimilate what was learned. But the advantage of removing uncertain assumptions from this critical region is that you can then argue for the conclusion with much more confidence. While the least important assumptions are not investigated for the moment, they should be monitored from this time forward. What was once least important may become most important at any time.

Figure 7

Revising the Assumption Matrix

The revised assumption matrix, adjusted for new information, now becomes the basis for deducing a new conclusion, as shown in Figure 8. In essence: What new conclusion derives logically from all the assumptions plotted in the matrix—particularly those in the two most important cells? In order to deduce a new conclusion, the members often realize that they do not have to consider their assumptions as fixed. As a result of having mastered assumptional analysis, the enlightened members develop a new assumption about assumptions themselves: Assumptions are the attributes of stakeholders; if members influence these attributes, any conclusion that is desired can become true! This insight epitomizes quantum thinking.

Figure 8

Deducing the New Conclusion

Figure 9 exhibits a pictorial summary of assumptional analysis: It should now be apparent that in order to minimize the errors of problem management, it is essential to surface assumptions (write them out explicitly), classify assumptions (according to their relative importance and certainty of being true/false), and synthesize assumptions (collect additional information about the validity of the most important/uncertain assumptions and then revise how the problem is sensed, defined, solved, and so forth—based on these revised, up-to-date assumptions). Most members eventually realize that assumptional analysis supplies them with a deeper—more accurate—approach for managing complex problems in their quantum world.

Figure 9

A Summary of Assumptional Analysis

CONCLUSION: A STORY ABOUT ASSUMPTIONAL ANALYSIS

A long time ago, I assembled twenty illustrious professionals in the field of change management for a nine-hour workshop. After expounding the basic technique of assumptional analysis, I organized them into three groups representing three divergent approaches to organizational change and improvement. The C-groups—short for initial conclusion groups—were delineated as human resources, organizational design, and organizational development. Each C-group was asked to formulate a list of stakeholders that would directly pertain to this initial conclusion: “Organizations that seriously desire to improve their overall performance and morale can best be served by implementing change initiatives that are generally affiliated with human resources (or organizational development or organizational design).” It was interesting to discover that the overlap in the three lists of stakeholders was roughly 95%. Specifically, all three C-groups pinpointed these prime stakeholders: shareholders, customers, suppliers, competitors, financial institutions, government agencies, the surrounding community, union organizations, prospective (future) employees, existing employees, senior managers, middle managers, supervisors, union members, families of employees, and prospective customers.

Before they were asked to list their assumptions, the C-groups first spelled out the change initiatives that define their specialty. The C-group composed mostly of human resources specialists quickly agreed that they are preoccupied with the match between individuals and designated jobs, now—and in the future. This match includes the functions of acquisition, allocation, utilization, maintenance, and development of people assigned to jobs. Thus, the people/job interfaces are the natural targets for most change initiatives among human resources experts.

The C-group made up of all organizational development specialists, however, was concerned with the quality of interpersonal relationships in the organization, the culture of the organization, and the establishment of trust, motivation, and commitment among members (and their subunits). Thus, culture and the people/people interfaces (including members-to-groups) are the prime targets for organizational development experts.

The C-group of specialists in organizational design took a different approach: The members of this C-group were primarily concerned about the formal structure of an organization’s departments and divisions and the prime methods of governance (for example, management hierarchies or self-managing teams). The focus for organizational design, therefore, is typically the subunit/subunit interfaces and the mode of coordination among these subunits.

Next each C-group proceeded to untangle its implicit assumptions about stakeholders and then presented them to the entire community of change experts. Even though every C-group knew, intellectually, that the three specialties were vastly different from one another, they still seemed very surprised to hear, in a live forum, just how different they really were. What concerned one C-group was dismissed or overlooked by the other two C-groups! Gradually, however, each C-group began to appreciate that the numerous attributes that they routinely disregard in their specialized approach have a dramatic impact on organizational success.

Two representatives from each C-group were then asked to form an integrated group, called a synthesis group, or S-group for short. The mission of the six-member S-group was to formulate an integrated assessment of the key assumptions underneath all three initial conclusions (which had been surfaced independently by each of the three C-groups) and then to propose a synthesis (a new conclusion) to this question: What integrated approach to transformation would help most organizations significantly improve their overall performance and morale? I now want to feature the fundamental assumptions that guided the S-group’s discussion and then summarize the “new tree” that was created within this quantum forest.

The S-group proclaimed that each specialty assumes that the other two specialties have already consulted with the organization in question and thus have already accomplished their change objectives. Specifically, human resources assumes that (1) the culture of the organization and the trust, motivation, and commitment of its members are already conducive to obtaining accurate assessments of people/job interfaces throughout the organization; (2) these cultural as well as people-to-people attributes have already attracted the most competent people (and will continue to retain these people) in the marketplace; (3) the current design of subunits in the organization (strategic business units, divisions, departments, and groups) is the most effective and efficient way of managing all the organization’s resources (including the mechanisms used to coordinate these work units) and these subunits have been operationalized into clear jobs throughout the organization. The S-group could see that these assumptions are most important—but highly uncertain—for change initiatives within the human resources specialty.

The S-group also proclaimed similar uncertain assumptions when focusing on either organizational development or organizational design: The former approach assumes that the proper design and coordination of subunits have already formed the best jobs for the present and the future; the latter approach assumes that the culture and members’ relationships are already adaptive, healthy, and receptive to change and improvement. Both approaches assume that the best people have already been attracted, rewarded appropriately, and retained by the organization.

When the S-group proceeded to synthesize the three specialties into one comprehensive approach (after revising and rewording many of the most important assumptions), a startling paradox caught their attention: How can each specialty justify its sweeping assumptions about the other two approaches when so many reports of failed efforts at transformation indicate that all the other attributes of the organization (addressed by the other two specialties) were also in dire need of change and improvement? As a result of struggling with this dilemma, the S-group began to realize that all three approaches to transformation are needed all of the time!

The new tree that the S-group firmly planted in the forest contained several branches emphasizing the sequence by which all three specialties should be brought into an organization: Should all three be implemented simultaneously? The S-group named this solution the shotgun approach. Or should all three specialties be brought into the organization, one after the other, depending upon who made the request and which consultant was available? The S-group characterized this solution as the adhoc approach. Or should the three specialties proceed harmoniously, right from the start, in designing and implementing a coherent, well-designed, well-orchestrated solution to change and improvement? The S-group considered this fertile branch a completely integrated program.

During this process, members of the S-group clearly saw the obvious limitations of the specialized categories that were instilled in their minds/brains. But through a creative interchange, they were able to derive a synthesis that not only made sense to them but also confirmed their extensive experience in change management. They also encountered intense contradictions in their professional paradigms, but they were able to create new categories in their minds and rewired their brains as well. While I don’t have the traditional scientific results to support this claim, I am convinced that these twenty experts fundamentally changed the way they see, think, and behave about organizational transformation. I surely know that I have: The eight tracks to quantum transformation became one subbranch on that new tree in the forest.