10 Apr A Completely Integrated Program for Creating and Maintaining Organizational Success

by Ralph H. Kilmann

An earlier version of this article was published in Organizational Dynamics (Summer 1989), pages 4-19.

INTRODUCTION

Freedom to determine one’s destiny is a recurring struggle for mankind. It is no less important to any modern-day organization. Members want to contribute to a worthwhile cause. Often, however, the organization holds them back. Members are caught in a bureaucratic grip, one that prevents them from fully contributing their talents and efforts to the organization’s mission. For them to get free from this grip, all barriers to success must be transformed into channels for success. Channels facilitate high performance; barriers keep the membership in a deadlock.

Every few years, a new approach is offered for unleashing the full potential of organized efforts. But this is like the search for the Holy Grail: Each new approach looks for the one single answer. For example, in the 1940s, human relations training was considered the key to organizational success. In the 1950s, management by objectives was heralded as the new solution to performance problems. In the 1960s, decentralizing the organization’s structure was believed to be the best solution. In the 1970s, corporate strategy was considered the next panacea. In the 1980s, the rage was corporate culture. Now in the 2000s, the topic for the day is globalization.

It is a shame that managers will have to learn the hard way—one more time—that more rhetoric—without real change—cannot solve their performance problems. Eventually, managers will drop the globalization fad and move on to the next promised remedy, and the cycle will continue. Single approaches are discarded because they have not been given a fair test. Essentially, it is not the single approach of culture, strategy, or restructuring that is inherently ineffective. Rather, each is ineffective only if it is applied by itself—as a quick fix.

It is time to stop perpetuating the myth of simplicity. The system of organization invented by humankind generates complex problems that cannot be solved by simple, quick-fix solutions. The only alternative is to develop a truly integrated approach—a complete program for managing today’s organization.

During my career, I gradually developed a completely integrated program for creating and maintaining organizational success. By complete I mean a program that integrates a wide variety of approaches—ranging from those that recognize the intrapsychic conflicts of individuals to those that act on the system-wide properties of organizations. By success I mean achieving both high performance and high morale over an extended period of time—an outcome that is only possible by managing all potential leverage points in the organization. The complete program consists of five tracks: (1) the culture track, (2) the skills track, (3) the team track, (4) the strategy-structure track, and (5) the reward system track. If any of these tracks is implemented without the others or is conducted out of sequence, any effort at improving performance and morale will be severely hampered. Any benefits derived in the short term may soon disappear. Lasting success can be achieved only by managing the full set of five tracks on a continuing basis. (Note: See my 2001 book, Quantum Organizations, which expands the five tracks to eight tracks, with the addition of three process tracks—gradual process, radical process, and learning process—after the five system tracks.)

First I will present three ways of viewing the world: as a simple machine, an open system, and a complex hologram. These contrasting world views highlight why an integrated approach is so necessary for organizational success and why any quick fix inevitably will lead to failure. Second, I will outline the five tracks, emphasizing the particular sequence in which they need to be conducted. As we shall see, one by one, each track sets the stage for the successful completion of the next track. And third, I will offer a challenge to top managers. Essentially, if executives do not take responsibility for change—moving their companies from a simple machine to a complex hologram via the five tracks—their organizations will not maintain whatever success has been achieved. Their organizations will continue to live in the past, hoping for a return to simplicity, perfection, and certainty. This never-never land is gone. Complexity must be fought with a completely integrated program.

THE HOLOGRAPHIC WORLD

The world as a simple machine argues for single efforts at change, much like replacing one defective part in some mechanical apparatus: The one defective part can be replaced without affecting any other part. This single approach only works for fixing a physical, nonliving system. The quick fix cannot hope to heal a human being, much less a living, breathing organization. The simple machine view represents one-dimensional thinking—much like studying the world as a collection of isolated cities.

The world as an open system argues for a more integrated approach, in which several parts must be balanced simultaneously in order to manage the whole organization. Here, a dynamic equilibrium exists between an organization and its changing environment. The organization consists of systems, such as strategies, structures, and rewards. The environment contains its own systems, too, such as the government, suppliers, competitors, and consumers. This world view, however, remains at the surface level, where things can be easily observed and measured. The open system represents two-dimensional thinking—much like studying the world with a flat map.

The world as a complex hologram argues for adding depth to the open system—analogous to forming a three-dimensional image by reflecting beams of light at different angles. Here, the complex hologram probes below the surface to examine cultures (shared but unwritten rules for each member’s behavior), assumptions (unquestioned beliefs behind all decisions and actions), and psyches (the deepest reaches of the mind). To ignore such deeper aspects of organizational life is to assume that what cannot be seen or touched directly is unimportant. The complex hologram represents three-dimensional thinking—much like studying the world with a relief map and with X-rays and sonar as well

I believe the simple machine view of the world is already outdated. It had its heyday in the industrial revolution back in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Yet, looking at the way contemporary organizations are designed and managed would lead one to conclude that the simple machine conception is alive and well.

Recently, I described the three world views—simple machine, open system, and complex hologram—to a diverse group of forty middle and top managers representing some of the largest industrial corporations in the world. I asked them to sort their organizations into the three categories according to which metaphor best illustrates how their organizations are designed and managed. More than 75 percent of this group indicated that their companies are being run as a simple machine! Then, I asked them to develop a comprehensive list of all their major organizational problems. Next, I asked them to sort these problems into the same three categories: simple machine, open system, and complex hologram. After an extended discussion, not one individual could think of one major problem that fit the category of simple machine! All problems were sorted into the complex hologram. This diverse group of managers came to the conclusion that most of their organizations are designed and managed for simple problems while none of the problems they actually face are of this variety. No wonder problems do not get resolved.The American system is designed for yesterday.

Even viewing the world as an open system requires that we recognize how every aspect of an organization is interdependent with every other aspect. Therefore, a problem in one area automatically creates problems in all other areas, thereby rendering the quick fix an impossible solution to any complex problem. A single approach that attempts to “fix” a problematic situation by influencing only one point and inadvertently or purposely ignoring all the interrelated aspects is doomed to fail.

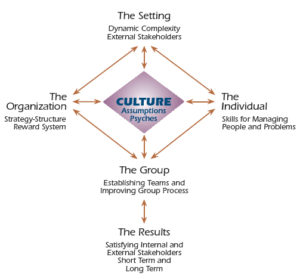

As shown in Figure 1, the world as a complex hologram not only includes the interrelated view of the open system but adds an assortment of unconscious and nonrational aspects of human life. What, then, is the likelihood that today’s organizations can cope with a new world by adjusting only one leverage point—such as strategy? It is very unlikely indeed. What about the possibility of being successful by adjusting a few but not all of the leverage points? This is just as unlikely, sorry to say. Rather, it seems that all leverage points at the surface (strategy, structure, and reward systems) and below the surface (culture, assumptions, and psyches) have to be considered and acted upon in all cases. This is the new rule for revitalizing our organizations, not the exception. Otherwise, the extent and variety of complex problems will continue to impose troublesome barriers to organizational success.

Figure 1

The Complex Hologram

THE FIVE TRACKS

When managers are asked what can be done to transform their organizations from simple machines to complex holograms, they are perplexed. Some assume that it cannot be done. Others are still waiting for the right quick fix to come along. Most are not aware of any alternatives to the quick fix. Nobody even knows what to call “it” other than a non-quick fix. Certainly, one important step in the right direction is to question the long-held assumption about revitalizing American industry: Can our organizations be changed? Are methods now available that can tackle such a complex arrangement of strategies, structures, rewards, cultures, assumptions, and psyches? The answer is yes, if managers and all employees will unlearn their old ways and be willing to adopt a new way of managing the holographic world around them: Quick fixes are to be avoided, integrated programs are to be embraced.

The five tracks to organizational success constitute a completely integrated program. Each track is implemented as a collaborative, participative effort among managers, consultants, and members. This is the best way I know to guarantee the success of the whole program. In some cases, however, top managers may prefer to practice the five tracks “top down” just as they ordinarily make decisions and take action; but this style will intensify some of the very problems they have to solve. In addition, I caution managers not to conduct single-handedly those aspects of the program that are clearly beyond their skills and experiences. At a minimum, consultants should conduct an independent diagnosis of the organization’s problems (regardless of what the managers may have discovered on their own), delicately guide the uncovering of cultural norms and assumptions, and manage difficult people and the team-building sessions (which can become very sensitive and uncomfortable). It is to be hoped that managers can recognize their limitations.

1. The Culture Track

The culture track is the ideal place to start the program, for several reasons. It is enlightening to openly discuss what previously was seldom written down or mentioned in any conversation. Members enjoy—even laugh at—the revelations that occur as dysfunctional norms (the unwritten rules of the game) are brought to everyone’s attention. It is also much easier to blame norms than to blame one-self or other people. As long as members take responsibility for change, it does not really matter if using norms as a scapegoat takes some pressure off their egos. Of prime significance, however, is that without an initial culture change, it is unlikely that the other four tracks can be successful. In many cases, cultural norms pressure members to: (1) keep information to themselves, (2) distrust managers at the next highest level, (3) disbelieve that anything will really change, and (4) discourage any new behaviors without question. It would be most difficult to teach managers and members new skills if these attitudes and beliefs guided everyone’s motivation to learn.

The culture track consists of a five step process: (1) surfacing actual norms, (2) articulating what is needed for success today, (3) establishing new norms, (4) identifying culture-gaps, and (5) closing culture-gaps. For example, some actual work group norms that may surface are: Don’t disagree with your boss; don’t make waves, treat women as second-class citizens; don’t share information with other groups; do as little as is necessary to get by. Often, work groups pressure each member to follow such dysfunctional norms out of habit—as in a culture rut. The culture track first exposes the old culture and then, if necessary, creates a new adaptive culture: Treat everyone with respect and as a potential source of valuable insight and expertise; initiate changes to improve performance; congratulate those who suggest new ideas and new ways of doing things; be helpful and supportive of the other groups in the organization. Controlling culture, rather than being controlled by it, gives the membership enough freedom to proceed with the next track.

2. The Skills Track

The skills track is needed because employees usually have not kept up with the holographic world in which they live and its dynamic, complex problems. They often have not developed the skills—conceptual, analytical, administrative, social, and interpersonal—to manage complexity. Traditionally, employees pick the first available quick-fix solution before they even bother to define the root causes of the problem and then, to top it all off, they implement the quick-fix solution in a mechanistic manner; not surprisingly, the problem never gets resolved. However, once managers are receptive to change—through the culture track—they and all employees can be taught the full range of skills needed to conduct a five step process for effective problem management: (1) sensing problems, (2) defining problems, (3) deriving solutions, (4) implementing solutions, and (5) evaluating outcomes.

The skills track also offers a systematic method for uncovering the underlying assumptions that drive all decisions into action. If these assumptions have remained unstated and therefore untested, employees may have continually made the wrong decisions. The deadliest assumption is referred to as erroneous extrapolation: What made the organization successful in the past will make it successful in the future.

Specifically, employees may have assumed: No new competitors will enter the industry; the economy will steadily improve; the government will continue to restrict foreign imports; the consumer will buy whatever the firm produces; employees will continue to accept the same working conditions. In short, all previous decisions may have been based more on fantasy and habit than on reality and choice. Outdated assumptions may have steered the organization into adopting the wrong strategies, structures, and reward systems as well. However, given a new culture that encourages trust and openness, members now will be able to analyze their previously unstated assumptions before any critical decisions are made. No longer will the membership be held back by its own faulty assumptions.

3. The Team Track

As the culture and skills tracks are encouraging new behaviors, skills, and assumptions, the next effort lies in directly transferring these learnings into the mainstream of organizational life. Specifically, the team track does three things: (1) keeps dysfunctional behavior in check so negativity will not disrupt cooperative team efforts, (2) brings the new learnings into the day-to-day activities of each work group, and (3) enables cooperative decisions to take place across work group boundaries, as in multiple team efforts. In this way, all available expertise and information will come forth to manage the complex technical and business problems that arise within and between work groups. As the culture opens up everyone’s minds as well as their hearts, work groups can examine, maybe for the first time, the particular barriers that have held them back in the past. Through various workshop sessions, old warring cliques become well-functioning teams.

4. The Strategy-Structure Track

Eventually it becomes time for the membership to take on one of the most difficult problems facing any organization in a dynamic and complex environment: aligning its formally documented systems. One might think that the mission of the firm and its corresponding strategic choices should have been the first topics addressed. Why should the organization proceed with changes in culture, management skills, and team efforts before the new directions are formalized? Is it not logical to first know the directions before the rest of the system is put in place? Yes, that is logical. But there are other things operating in a complex organization besides logic. If we understand culture, assumptions, and psyches—the holographic view of the world—we recognize that it makes little sense to plan the future directions of the firm if members do not trust one another and will not share important information with one another, expose their tried-and-true assumptions, or commit to the new directions anyway because the culture will not allow it. If the prior tracks have not accomplished their purposes, the strategy-structure problem will be addressed through politics and vested interests, not through an open exchange of ideas and a cooperative effort to achieve organizational success.

The strategy-structure track is conducted in an eight step process: (1) making strategic choices, (2) listing objectives to be achieved and tasks to be performed, (3) analyzing objective/task relationships, (4) calculating inefficiencies that stem from an out-of-date structure, (5) diagnosing structural problems, (6) designing a new structure, (7) implementing the new structure, and (8) evaluating the new structure. As a result of this process, the members remove a two-sided barrier to success: bureaucratic red tape that moves the organization in the wrong direction. In its place is a structure aligned with the firm’s strategy.

5. The Reward System Track

Once the organization is moving in the right direction with the right structure and resources, the reward system track completes the program by making sure that rewards vary directly with performance. The formal system is designed via a seven step process: (1) designing special task forces to study the problem, (2) reviewing the types of reward systems, (3) establishing several alternative reward systems, (4) debating the assumptions behind the alternative reward systems, (5) designing the new reward system, (6) implementing the new reward system, and (7) evaluating the new reward system.

The reward system also specifies how performance results and reward decisions are communicated to each member of the organization during face-to-face meetings with a superior. In essence, two different types of meetings are necessary: (1) a performance review to provide information for evaluative purposes and (2) a counseling session to provide feedback for learning purposes. These two types of meetings ensure that members understand their performance results and will be able to improve for the next cycle—taking into account human nature.

INTEGRATING ALL FIVE TRACKS

The reward system track is futile if all the other tracks have not been managed properly. Without a supportive culture, members will not believe that rewards are tied to performance—regardless of what the formal documents state; instead, they will believe that it is useless to work hard and do well since rewards will be seen as being based on favoritism and politics. Similarly, if employees do not have the skills to conduct performance appraisal, for example, any well-intentioned reward system will be thwarted; the arousal of defensiveness will inhibit each member’s motivation to improve his performance. Without effective teams, employees and members will not be comfortable in openly sharing such information as the results of performance reviews and the distribution of rewards; in the absence of such information, imaginations will run wild since nobody will know for sure whether high performers receive significantly more rewards than low performers. Furthermore, if the strategy and structures are not designed properly, the reward system cannot measure performance objectively; only if each group is autonomous can its output be assessed as a separate quantity.

What if individuals disregard the formal reward system and strive to excel for intrinsic rewards, such as personal satisfaction for a job well done? If the other tracks have not been managed properly, even the most dedicated efforts by the members will not lead to high performance for the organization. Instead, members’ efforts will be blocked by all the barriers to success that are still in force: dysfunctional cultures, outdated management skills, poorly functioning work groups, unrealistic strategic choices, and misaligned structures. Alternatively, whatever improvements were realized as a result of the earlier tracks will not be sustained if the membership is not ultimately rewarded for high performance: the old dysfunctional cultures, assumptions, and behaviors will creep back into the work place. Thus, the reward system is the last major barrier that must be transformed into a channel for success, the “bottom line” for the membership.

To illustrate the integrated nature of the five tracks, consider the following scenario: If I could investigate only one aspect of an organization in order to predict its long-term success, I would choose the reward system. In essence, if members feel that (1) the reward system is fair, (2) they are rewarded for high performance, and (3) the performance appraisal system regularly provides them with specific and useful information so that they know where they stand and can improve their performance, then, in all likelihood, all tracks have been managed properly. The reward system could not motivate members to high performance if all the other barriers to organizational success have not been removed by the preceding four tracks. Thus, a well-functioning, performance-based reward system generally signifies that the organization is ready for whatever problems and opportunities will come its way.

One difficult question is always asked: “How long will the whole program take?” My response is: “I can’t say exactly; I can only suggest some rough guidelines from my prior experience.” These guidelines consider the size and age of the organization, the complexity and severity of the problems facing the organization, the time available for conducting the five tracks, and the desire on the part of both managers and members to learn. Since the organization cannot shut down its operations just to engage in a change program, the five tracks have to be conducted as other work gets done—even during crises and peak seasons.

In general, one can expect most change programs to take anywhere from six months to five years; there is no shortcut to organizational success. Less than six months might work for a small division, in which the formally documented systems—strategy, structure, and reward systems—need only a fine tuning. However, a program taking more than five years might be necessary for a very large, old organization involving major breaks from the past in every way. If the program were to take more than ten years, I would assume that there was insufficient commitment over this period, which prevented the momentum for change to prevail.

THE CHALLENGE

All members in every organization have heard the message: The world is characterized by dynamic complexity. Why do organizations still act as if the world is a simple machine? Why do managers speak of complexity yet act out of simplicity? What does it take to finally come to grips with a holographic world? Will top managers commit beyond the quick fix?

The realization of the American dream rests on the promise of commitment. If top managers do not act on this promise, the five tracks and all other efforts at providing integrated programs will be wasted. Chief executives will continue to search for the Holy Grail, whether it be a magical machine to solve their technical problems or a quick fix for their organizational problems. Continuing with such misplaced efforts eventually will decrease our productivity as a nation, threaten our standard of living and political freedom, and erode our position of world leadership. The alternative is to address the fundamental problem facing our society today: Failure to place a long-term total commitment behind an integrated program for organizational success.

Commitment to act—to put oneself on the line, to risk failure and humiliation—is a very difficult proposition. Most individuals are uncomfortable with the idea of fully committing to anything, whether it be another person, an idea, or an integrated solution to a complex problem. Some managers are so afraid of being held responsible that they do not act. Other managers are willing to act as long as they can blame someone else for the results. However, as Harry Truman once said regarding responsibility in the Oval Office: “The buck stops here!” For CEOs, so also stops certainty and precision in all that transpires. Thus, accepting personal responsibility for success amidst uncertainty and imperfection is the only way top executives can move forward in a holographic world. Only in the world as a simple machine can executives expect absolute guarantees before they take action.

One of the reasons CEOs are willing to spend so much time and money on one quick fix after another is that they know in their hearts that the quick fix will not change much of anything. The quick fix is the best way to avoid responsibility: It diverts the organization’s energy while absolutely maintaining the status quo. Although no one will benefit from the quick fix, the important thing is that no one will get hurt either! The quick fix is relatively safe—and therefore perfect—from the point of view of top executives who still believe in the simple machine and are unwilling to accept responsibility for change.

The five tracks to organizational success are at hand. The need for a holographic approach to revitalizing American industry is clear. It is time to move beyond the quick fix. Will CEOs commit their organizations to success?