10 Apr The Costs of Organization Structure

by Ralph H. Kilmann

An earlier version of this article was published in Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1983, pages 347-357.

ABSTRACT

For theoretical and methodological convenience, accountants often assume that the divisions of an organization are largely independent of one another and that divisional managers therefore can make decisions consistent with global optimality. Along with these assumptions, accountants have taken the structure of an organization as fixed and not changeable. This paper suggests a framework and method for assessing the costs resulting from non-independent divisions, as a component of organization productivity. Also offered is a methodology for changing the structure of organizations so that these hidden “conversion costs” first will be exposed and then can be managed for productivity improvements. Structural change thus becomes an alternative to designing elaborate information/control systems as a way of managing interdependency problems. Furthermore, as organizations are redesigned to make divisions more independent, accountants can concentrate on more intermediate matters, such as procedures for optimally determining joint-cost allocation and transfer prices, with minimal interference from the divisional structure of the organization.

INTRODUCTION

Real organizations are always more complex than our theories would lead us to believe. Initial theories are based upon rather simple assumptions about human nature, the environment, and the interaction between these two. In order to improve the validity and usefulness of theories, one by one the simple assumptions are questioned, researched, and then replaced by more sophisticated, complex, and generally truer assumptions of human behavior.

So has been the development of economic theory and accounting procedures as aids to management decision making. It has become apparent that human actors do not respond according to the implicit assumptions of earlier accounting theory – as purely rational, all-knowing, decision optimizers – but respond according to ego needs, self-interests, social motives and for political reasons (Argyris, 1951; Ridgway, 1956). Recent theories about how individuals respond to various accounting systems have been made more complex and realistic (Hopwood, 1976), but now it seems that assumptions about the system of organization itself – the environment of human behavior – need to be challenged and modified.

One set of assumptions that has been quite central to economic theory and accounting research concerns the structure of organizations. First, it has been assumed that the existing division of labor as formal organizational divisions or departmentalization is correct, fixed, and unchangeable. Current accounting procedures, in most cases, simply take the divisional structure of the organization as a given. Second, the implicit assumption behind most accounting procedures is that the divisions are independent entities, where the manager of each division has the requisite authority to make decisions without being responsible for, or concerned with, the decisions taking place in other divisions. In particular, it is hoped that if each divisional manager makes a local-optimal decision then the total set of decisions will combine to yield an optimality for the organization as a whole. This assumes, of course, that each manager can act as if he is not coupled with the activities of other divisional managers.

Already, a few researchers have recognized the simplicity of these assumptions of organization structure, even though the possibility of changing the structure to facilitate decision making for global optimality rarely has been mentioned. Three decades ago, Simon e, al. (1954, p. 41) suggested that . . . “where the activities of two or more divisions of a company are in fact highly interdependent, it is very difficult to allocate total company profits among the divisions in a rational, precise manner. Under these circumstances, it becomes questionable as to how much weight can be placed upon these divisional ‘profits’ in determining the effectiveness of the divisional executives. “This stems, for example, from the difficulty in allocating joint costs and establishing transfer prices among interdependent divisions. Recently, Birnberg et al. (L983) conclude, “Although it [the accounting literature] has admitted the existence of interdependencies among divisions of varying sorts; accounting researchers have repeatedly devoted inordinate amounts of time to resolving these interdependencies so that decision makers may behave as if the interdependencies do not exist.”

The typical way that the problem of divisional interdependencies is “resolved”, consists of providing managers with an information and control system to guide their local, divisional decisions toward global, corporate decisions (Thomas, 1980). Presumably, the information system allows each manager to be aware of what relevant decisions have been made by his counterparts in other divisions, and the control system attempts to motivate each manager to include this information in his own decision making. However, there is certainly a cost involved in designing and maintaining such information/control systems, especially when there are significant interdependencies among divisions requiring extensive use of these systems. Ultimately, the costs of this solution to the interdependency problem should be compared to the costs of an alternative solution – one that changes the structure of the organization’s divisions in the first place.

This paper thus argues for an opposite set of assumptions regarding organization structure: (1) divisions are often highly interdependent with one another, and because of this, (2) divisional managers have less authority to make decisions than their responsibilities require, and (3) separate divisional decisions will result in significant departures from global optimality due to the costs (prices) that fall between the “cracks” (divisional boundaries). Even more central to this paper, is the revised assumption: (4) an organization’s structure of divisions can be changed to decrease the interdependencies among the divisions and, hence, to make the divisions more independent of one another. But the latter occurs by proactive, planned changes in organization design, neither by evolution nor by assumption.

Accountants, therefore, do not have to take the structure of organizational divisions as a given. Nor do they have to rely on designing an information/control system to cajole managers’ behavior toward organization-wide decision making. Ironically, after an organization has been restructured to remove substantial interdependencies across divisions, it will be easier to rely on information/control systems to shape decisions toward optimality than when there are considerable interdependencies across divisions. In the latter case, it will be argued, the interdependencies – with their corresponding impact on interdivisional conflict and the intensification of divisional vs. organizational loyalty – would render such a shaping effort immense and impractical. Under these conditions, it becomes quite inappropriate to proceed as if interdependencies do not exist. In fact, one might expect a whole host of unintended dysfunctions to develop when control systems push managers to take account of many activities and decisions taking place in other divisions that are not under their control.

A framework and method is proposed for conceptualizing the impact of organization structure on performance and productivity. Also presented is one possible approach for assessing the costs of organization structure – one that assumes that varying degrees of interdependencies can and do exist across divisions. Then a method will be offered for restructuring an organization’s divisions so that the interdependencies are switched from between divisions to within divisions. This allows managers to expose and then recoup the “conversion costs” that were hidden across divisional boundaries. This allows accountants to “optimize” the budgeting process, cost and price allocation, performance evaluation, and the like.

ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE

While structure has been defined in numerous ways in the literature on organizational theory and behavior (Evan, 1976; Hall, 1977; Kilmann et al., 1976; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1962; Mackenzie, 1978b; Meyer, 1977), I find it useful to concentrate on: (1) objectives to be pursued, (2) tasks to be performed, (3) the arrangement of objectives and tasks into divisions, and (4) the management hierarchy that seeks to coordinate the separate divisions into a functioning whole. To make this structure operational requires that specific people be assigned to each division in order to perform specified tasks with the relevant objectives in mind – as in the division of labor or “departmentalization”. Beyond this, various policies, reward systems, rules, ‘job descriptions, and so on are utilized to ensure that the “system” functions as intended, However, rather than including all these various control mechanisms, it is sufficient for the purposes of this paper to view structure as objective/task arrangements divided into divisions, which are then assigned to organization members. In addition, while structure has been discussed as span of control, chain of command, formalization of tasks, centralization of authority, locus of decision making, and the like, this paper concentrates on the most neglected aspects of structure: departmentalization and factorization of objective/task responsibilities and people (March & Simon, 1958).

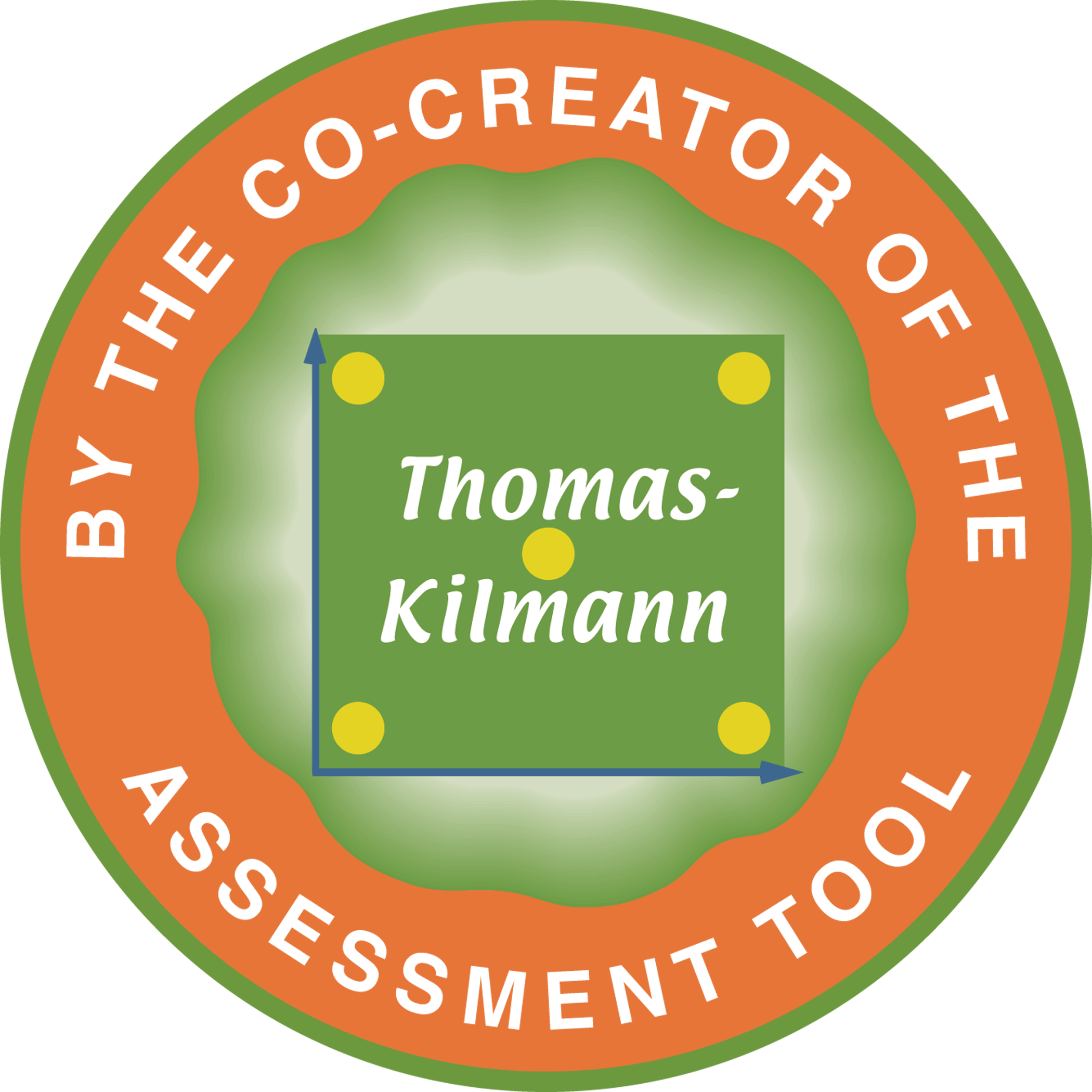

Figure 1 shows how an organization structure becomes operational by showing each division as a collection of objectives, tasks and people, coordinated through a management hierarchy. This diagram is different from a typical organization chart in that objectives are included formally as a part of each division and the people in each division are also specified. Incidentally, it should be apparent that the organization’s total set of objectives and tasks are subdivided into divisions in order to achieve the benefits of specialization.

Figure 1. Organization Structure

The topmost circle on the chart signifies the total set of objectives, tasks and people in the organization that would be the responsibility of the president of the organization or whomever is assigned to have the chief responsibility for all the organization’s resources. The next level breaks this total set of objectives, tasks and people into divisions, defined as the first decomposition of the whole into pans. Each of these divisions is responsible only for its assigned subset of objectives, tasks, and people. At the next level, each of the divisions in turn is divided into smaller, more specialized subunits, with an even more focused set of objectives, tasks and people, These may be departments, sections, teams, or work units. Depending on the scope and size of the organization, the decomposition of subunits continues until the job level is reached – where at most five to fifteen people, as a work group, are assigned the most detailed and specialized tasks that can be specified. The resulting linkages that emerge from this level-by-level decomposition of objectives and tasks becomes the management hierarchy. Its purpose is to coordinate the inputs and outputs that flow across subunit boundaries at each level in the organization.

Although the concept of structure can be examined at any level in the hierarchy (as shown in Fig. 1), most of the discussion in this paper concerns the first decomposition, the division. As will be seen, if the divisional level is designed incorrectly, considering the further decomposition of each division into departments and then departments into work units is a meaningless exercise. The structural errors at higher levels are carried through to the lower levels, automatically. On the other hand, one can take each division as a whole unit and then consider the next decomposition into departments as the point of interest and then apply the same analysis as is done for the whole organization – as long as the decomposition of all divisions is “correct” in the first place. For convenience sake, however, the term “subunit” will be applied in the following discussions to refer to a decomposition of the whole into parts that usually implies a division, but also can be taken as a department or work group, depending upon the focus.

Determining subunit boundaries

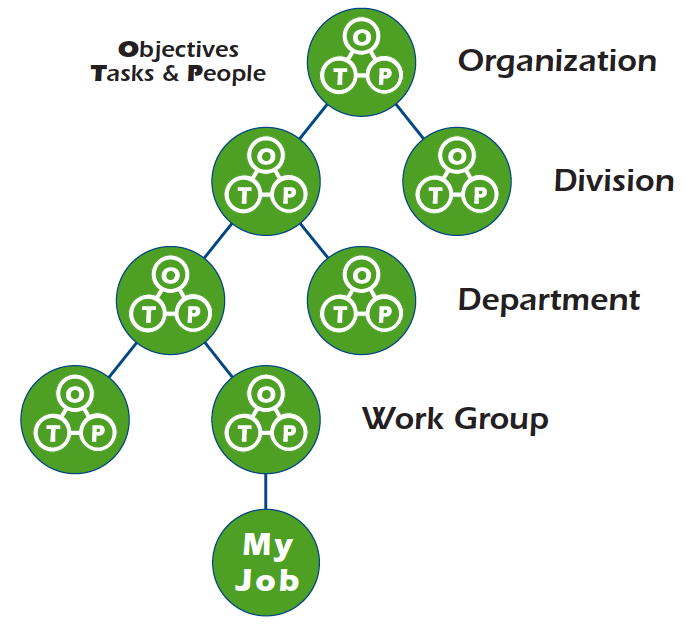

A critical question to address is: what determines or should determine the boundary of each subunit? That is, how should the subunits be sub-divided level after level? The guiding assumption is that it might make a critical difference on how all the objectives, tasks, and people are organized into separate subunits, particularly with regard to the relative ease or difficulty in coordinating these subunits into a functioning whole. James Thompson’s (1967) concepts of task interdependencies are exceedingly helpful here. Thompson defined three types of interdependencies that can occur among tasks, pooled, sequential and reciprocal. A pooled interdependency means that two or more tasks can be performed independent of one another and the outputs from peoples’ efforts on these tasks can be combined at some later time for desired, overall output. A sequential interdependency occurs when task t has to be performed before task 2, and then task 3 has to wait on task 2, etc. before useful, overall output would result. Finally, a reciprocal interdependency is evidenced when a constant input/output interrelationship has to take place among several tasks in order to derive useful output. Thus the individuals performing tasks 1, 2 and 3 would be interacting frequently in order to coordinate all their efforts. Figure 2 diagrams the three types of interdependencies.

Figure 2. Identifying Task Interdependencies

Thompson suggests that each type of interdependence varies in the cost of coordinating the interdependency. For instance, it is expected that pooled interdependence is the least costly simply because the outputs of different tasks can be combined easily by pre-determined rules and procedures. Sequential interdependence would be more costly than pooled to coordinate, since a certain amount of planning and scheduling would have to be done to ensure the proper workflow. But reciprocal interdependence would be the most costly to coordinate as “mutual adjustment” and frequent monitoring of input/output transactions would be required above and beyond schedules, plans, rules and procedures. Not surprisingly, reciprocal interdependence is the most troublesome for inclusion in accounting theory and methods.

Thompson argues that subunits should include the more costly forms of interdependencies within as opposed to between subunit boundaries. Ideally, all of the tasks that are reciprocally interdependent and most of the tasks that are sequentially interdependent would be placed within the same subunit; whereas tasks that have a pooled interdependency can be left to fall between subunit boundaries. It should be apparent that in most or all real organizations, more tasks are interdependent than independent. Therefore, in order to subdivide a complex set of objectives and tasks into manageable subunits requires that some important interdependencies will cross subunit boundaries. The design criterion, then, is to decompose the overall set of objectives and tasks into a hierarchy of subunits down to the work group level, where at each level, as much as possible, reciprocal and sequential interdependent tasks are placed in the same subunit rather than in different subunits.

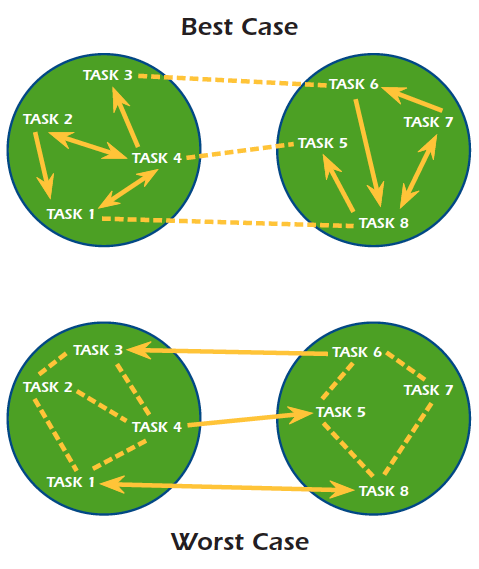

Figure 3 shows this design criterion diagrammatically by first portraying the ideal case and then the worst possible case. The ideal case has only pooled interdependence between subunits while the worst case has reciprocal and sequential interdependence between boundaries. The more that an actual organization has its boundaries designed close to the ideal, the lower the costs of coordinating interdependencies across subunits, all else equal.

Figure 3. Forming Subunit Boundaries

Understanding Subunit Boundaries

Perhaps it would be worthwhile to elaborate on just why additional costs are incurred when tasks are coordinated between rather than within subunit boundaries. While Thompson speaks of the relative costs of rules and procedures vs. schedules and plans vs. mutual adjustments, one can also consider the impact of group loyalties and reward/control systems.

Briefly, whenever a boundary is drawn around a cohesion of people, a group or team emerges that provides a strong psychological bond among its members. A “we” versus “they” attitude tends to reinforce the strength of the subunit boundary, and consequently, intergroup and interdepartmental competition become manifest (Blake & Mouton, 1961; Julian & Perry, 1967; Seiler, 1963). Such “social forces” make coordination between subunits even more difficult, time consuming, and hence, costly.

In addition, most organizations seem to design and implement their reward systems so that the subunit manager controls the distribution and withholding of rewards. For example, subunit managers often have a significant input (if not sole authority) in the hire/fire decisions, wage and salary increases, promotion decisions and the like. Such authority over important rewards to members tends to reinforce further the members’ loyalty and adherence to subunit objectives, more so than overall organizational objectives, let alone some other subunit’s objectives. As a result, it is not surprising that managers who are responsible for coordinating workflows across subunit boundaries, spend considerable time (cost) in negotiating disagreements, misunderstandings and all sorts of conflicts (Blake et al., 1954; Thomas, 1976).

In summary, if subunit boundaries could be designed to have each subunit contain interdependent objectives and tasks, which at the same time are as independent as possible from the objectives and tasks of other subunits, then coordination costs that ordinarily result from inter-unit planning and conflict would be minimized. On the other hand, the extent that reciprocal and sequential interdependencies exist across subunit boundaries, the more that organizational resources are being absorbed as unnecessary coordination costs (Thompson, 1967).

ORGANIZATION PRODUCTIVITY

While numerous definitions and perspectives have been offered, it seems that the ratio of organizational output to input highlights the main focus of productivity (Jehring, 1962; Siegel, 1980; National Center for Productivity, 1978; Militzer, 1980). Output refers to the market value of what the organization provides in the way of products and or services, including both quality and quantity. Input refers to the whole host of resources utilized in the “production process”, namely, labor, capital, technology, and materials (Kendrick, 1962). Efforts to improve productivity, therefore, would have to: (a) increase output with the same quantity of input, (b) maintain the same output levels with a decrease in input, or (c) some combination of (a) and (b).

The traditional approaches to productivity improvements can be classified as: (1) developing new, innovative methods of production (i.e. decreasing the cost of direct labor to produce a given output), (2) motivating members to exert more effort and energy in the production process than they did previously (i.e. getting more “labor output” from the same cost of labor input), (3) developing new products and/or services which can provide a higher value of output for the organization (i.e. producing a more valued product for the market place with the same inputs), and (4) acquiring materials/components from other organizations which are less costly than attempting to produce these “from scratch” by the organization’s own production process.

Misdirected Conversion Costs

The perspective on productivity taken in this paper continues in the tradition of emphasizing the output-to-input ratio. A variation, however, is to make use of the concept termed “conversion costs”, defined as the time (hence, cost) of members working on tasks toward the accomplishment of organizational objectives: converting inputs to outputs (Katz & Kahn, 1978). In other words, one can consider the time spent on tasks as a way of specifying how organizational resources have been allocated toward productive ends (presumably, organizational objectives). Thus, rather than attempting to distinguish labor from capital from technology from materials, as separate sources of productivity, it seems that the common dimension of time spent by members making use of these various resources is just what an organization should be productive about. Mackenzie (1981) takes a similar approach.

What would be considered unnecessary or misdirected conversion costs? Members would be: (a) spending time on tasks that are deemed not necessary or central to accomplishing objectives, (b) not spending enough time on the important tasks that are central to organizational objectives, (c) not being permitted to work on the important tasks because these have been assigned, perhaps incorrectly, to some other subunit, and (d) not being given the opportunity to suggest what new tasks need to be defined and specified so that organizational objectives can be pursued more effectively.

It should be apparent now that productivity can be improved by decreasing the misdirected conversion costs, that is, by shifting the time spent on the wrong tasks or the wrong time spent on the right tasks to the right time on the right tasks. Here, the right time and right tasks are defined as the resource allocation on the tasks (activities) that will lead to accomplishing organizational objectives.

Defining productivity in this way affords the possibility of linking productivity to the earlier discussion on organization structure. Specifically, the purpose of structure is to determine the allocation of people to tasks to objectives for each defined subunit in the organization. If each subunit has the right set of people, tasks, and objectives, then it is more likely that: (1) misdirected conversion costs are already at a minimum, or (2) misdirected conversion costs can be corrected within each subunit in the organization. Thus, the allocation of resources (labor, capital, technology, materials), in this case, can be aligned rather easily with the appropriate people, tasks and objectives, subunit by subunit.

Consider the opposite case, where people, tasks, and objectives have been designed into subunits with significant reciprocal and sequential interdependencies existing between (across) subunit boundaries. It would be most difficult to correct (decrease) misdirected conversion costs within each subunit precisely because so much of the work flows between rather than within subunits. Simply put, how can individuals be asked to spend more time on tasks located in some other subunit in the organization? Not only do managers not have the authority to reallocate their subordinates’ time on tasks in another subunit (at the same level in the hierarchy) but the dynamics of group loyalty and subunit reward systems do not encourage such resource transfers, as discussed earlier. In fact, the forces for members’ identifying with their own subunit interests and objectives get in the way of reallocating resources across subunit boundaries. Even if the next highest level of authority were brought into the reallocation process, intergroup competition and negotiating different interests and demands across subunits would be time consuming, and hence, costly. Ironically, the efforts by the next highest level in reallocating resources across subunit boundaries might cancel out whatever savings are gained by the resultant inter-unit compromises or solutions. In other words, the efforts to resolve inter-unit allocation problems are themselves a misdirected conversion cost, as are efforts to design and manage an information/control system just to make up for the interdependency problems across divisions!

Restructuring for Productivity

The primary reason for restructuring the organization, according to the principles of task interdependency, is to minimize misdirected conversion costs and, thereby, to improve productivity. It must be considered unlikely that the allocation of resources could be appropriate if the design of subunits does not contain the important task interdependencies within subunit boundaries. Further, given that the environments of organizations have been becoming more dynamic and given the more proactive approach that organizations have taken with their strategic planning activities (i.e. changing strategic choices), it is increasingly likely that organizations do have misdirected conversion costs, There is some evidence to suggest that organizations do not change their structures at all or until absolutely necessary – only after everything else has been tried to solve a particular problem. With continuous environmental and strategic changes, therefore, the current structure is likely to be the one organizational system that is most out of alignment with the desired state. Consequently, there will be more pressure to improve productivity via a reduction in structurally based, misdirected conversion costs.

A second reason for restructuring the organization along the lines suggested here is to facilitate the development of new work methods. Basically, the more that task interdependencies cut across subunit boundaries, the more that new work methods have to be implemented across these boundaries. The same difficulties arise from this as in the problem of reallocating resources. Much effort in conflict management regarding inter-unit competition takes place when several subunits have to coordinate work changes – where the work methods in one subunit require certain changes in another subunit in order for the new work procedure to capitalize on its potential improvement to productivity. Again, it is much easier to motivate and implement such improved work methods if these are confined more within vs. between subunit boundaries. In essence, any contemplated change that would cut across subunit boundaries because of strong task interdependencies necessarily limits the possibilities for productivity improvements; whether these changes be shifts in resource allocation, alterations in work methods, new technologies, products and services, modified material components to existing product lines, and so on.

A third reason for restructuring the organization is to facilitate the use of accounting procedures for management decision making. As was argued in the introduction of this paper, most accounting theories and methods have assumed independent divisions (subunits) where divisional managers collect information and make decisions for a global optimality. The more that organizations can be redesigned to meet these assumptions and conditions, the more that existing accounting procedures would be appropriate and useful. The opposite alternative is counterproductive: keeping divisional structures fixed will generate considerable misdirected conversion costs for organizations, will limit the development of new work methods, and will continue to render current accounting methods inappropriate for highly interdependent divisions.

Distinguishing Productivity Interfaces

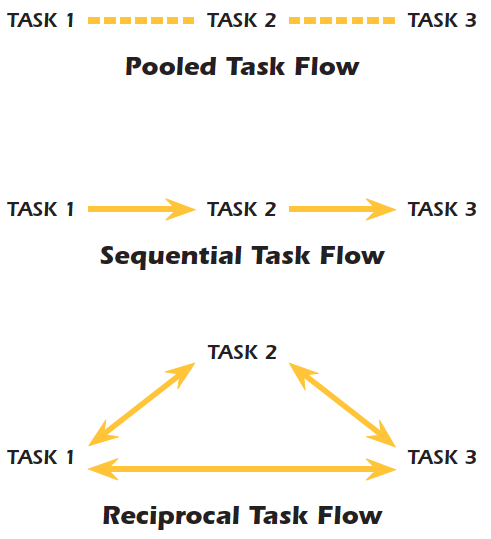

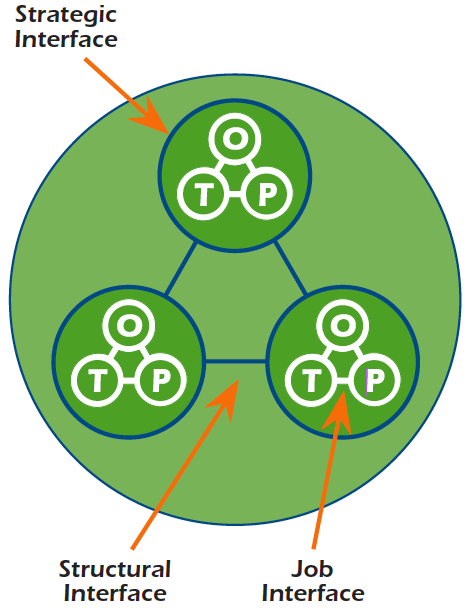

The foregoing has sought to relate the concept of misdirected conversion costs to restructuring the organization for productivity improvements. As a way of formalizing this relationship, it is possible to distinguish three productivity interfaces: the strategic interface, the structural interface, and the job interface, similar to Anthony’s (1965) three levels. Figure 4 shows how each of these interfaces portrays a different aspect of productivity while recognizing the critical linkage that is provided by the structural interface.

Figure 4. Organization Structure and Productivity

The strategic interface asks whether the overall purpose (mission) of the organization: (a) is realistic and appropriate given the environment outside ‘the organization and given the resources and capabilities assessed within the organization, and (b) has been operationalized effectively into specific objectives and tasks for the organization. Stated differently, are the objectives and tasks that will be (are being) utilized to design subunit boundaries and to guide activity within each subunit, the right objectives and tasks for the organization?

The structural interface asks how well the critical task interdependencies (reciprocal and sequential) have been placed within, rather than between, subunit boundaries. Presumably, even if the objectives and tasks are right for the organization, the structuring of subunits could prevent or restrict organizational activity from taking place productively, as discussed earlier (the structure as fostering misdirected conversion costs).

The job interface asks how well subunit man agers have sought to reduce the misdirected con version costs on the objectives, tasks, and people under their authority (jurisdiction). It is one thing for the reduction of misdirected conversion costs to be hampered by an inappropriate design of subunits; it is another thing for productivity to be limited by managers who have the authority to reduce misdirected conversion costs within their subunit and yet fail to do so (for one reason or another, such as incentives, awareness, ability to manage, etc.).

The interrelationship of all three productivity interfaces is as follows. If the strategic interface is not conducted properly, the remaining two levels are irrelevant. In this case, the structural interface would be decomposing the wrong objectives, tasks, and people into subunits, and managers at the job interface level would be allocating peoples’ time on the wrong tasks toward the wrong objectives (at the extreme). If the strategic interface is conducted properly but the structural interface is not, then the job interface still cannot go about its purpose effectively. However, even if both the strategic and the structural interfaces are done properly, it is still up to the managers at the job interface to allocate the peoples’ time to tasks to best accomplish objectives – but here the managers have under their jurisdiction, the right objectives, tasks, and people. Now the proper alignment can take place, if managers’ decisions and actions are guided by the right reward/control system.

It is essential, therefore, that all three interfaces are managed properly: first determining the right objectives, tasks, and people for the organization, then decomposing these into subunits that are as independent from one another as is possible, and finally allocating peoples’ time on tasks to accomplish objectives.

RESTRUCTURING ORGANIZATIONS FOR PRODUCTIVITY IMPROVEMENTS

This perspective on productivity draws attention to the intervening role that is played by the organization’s structure of subunits. Of course, as was shown above, all three interfaces of productivity must be managed effectively, but it seems that the structural interface has been the most ignored in the management of organizations. The literature documents many approaches and efforts at strategic planning and strategic management (Ansoff, 1965; MacMillan, 1978; Barnard, 1938; Andrews, 1971; Schendel & Hofer, 1979). Also, the literature provides numerous concepts and methods for dealing with the operational or job design level (Davis, 1971; Rush, 1971; Umstot et al., 1976). Few approaches exist to tackle the “in-between” interface, where strategic planning leaves off (once the organization’s purpose has been articulated and subsequent plans and policies outlined) and before day-to-day management begins (Chandler, 1962; Mackenzie, 1978a; Pheysey et al., 1971). Again, it seems that most theories and methods assume that the divisional structure of the organization is correct and is not subject to change.

Using the concepts and measures of cost accounting (Dopuch et al., 1982) as well as certain multivariate statistics which form clusters (boundaries) around highly interrelated variables (e.g. tasks and objectives) (Harman, 1967), it is possible to propose a method that: (1) assesses the misdirected conversion costs of an organization, (2) assesses how well the current subunits have been designed to contain the important task interdependencies, (3) provides an alternative (optimal) design of organizational subunits that maximizes the containment of reciprocal and sequential interdependencies within subunit boundaries, and (4) shows how much this new structural form can improve productivity (in dollars of savings) in contrast to the current design. This method, therefore, would provide the organization not only with a current assessment of its misdirected conversion costs, but also with a plan for restructuring subunits so that the “potential for productivity” (to be defined shortly) will be acquired.

Assessing Misdirected Conversion Costs

The first step in assessing misdirected conversion costs seeks to assure that the strategic interface of productivity is conducted properly – which sets the stage for the proper management of the structural and job interfaces. Specifically, the members of the organization, utilizing a participative process, are asked to formulate a listing of the organization’s objectives and tasks, given the defined purpose and strategic plan adopted by the organization (Kilmann, 1977). It may take a few days to a few weeks to develop the “objectives dictionary” and the “tasks dictionary” depending upon how familiar the organization is with specifying objectives and tasks. Eventually the two dictionaries would comprise items that are well understood by all members (i.e. no jargon or ambiguities) and no member would feel that any important objective or task has been left out. Often the dictionaries go through a number of iterations and extensive editing before this point is reached. In any event, a “typical” organization may identify 30-50 objectives and 50-100 tasks. Even if many more objectives and tasks were developed through the participative process, usually these can be reduced to the indicated range by removing the redundant items.

Some selected examples of objectives are: continue cost reduction efforts consistent with maintaining quality image; improve market share through the introduction of new products for high growth sub-segments and sales channel developments; continue to use master distributors and brand naming to increase market share; develop and implement an extensive value differentiation program to capitalize on total organizational product offering; and maintain parity or leading cost position in all product lines. These objectives are more specific than a general statement of the organization’s basic mission or purpose and yet these are not so specific that they define what has to be done in terms of task performance. Examples of tasks are: design new and modified products; build and maintain tools, jigs, etc.; product cost and inventory accounting; budgets, forecasts, and measurements; market analysis; materials handling; requisition engineering; technology study; sales promotion; pricing; and packing and shipping. These tasks, as the examples suggest, would not be so detailed as to describe day-to-day activities but they would be more specific than the basic management functions (e.g. production, finance, and marketing).

The next step in the process requires all members in the organization to respond to the items in the objectives dictionary and the tasks dictionary. Each member is asked to respond on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all”, 7 = “extremely so”), to each objective according to the following typical instruction: “Please indicate the extent to which you have the interests and the ability to contribute to each of the following objectives. ” Next, each member is asked to respond on the same type of scale to each task: “Please indicate the extent to which you need to participate directly in, or be aware of, each of the following tasks in order to accomplish your organizational objectives.” Each member is then asked to distribute 100 percentage points across the list of tasks according to his/her average/annual time actually spent on each task. Responses might be, 5% on task 1, 20% on task 5, 10% on task 21, etc., realizing that all the percentages would add to 100%. Lastly, each member is asked to distribute percentage points across the list of tasks – now according to how much time he/she should be spending on each task in order to contribute best to organizational objectives (again adding to 100%) (Kilmann, 1977).

One can suggest several calculations that are possible with this information as well as additional information available from the personnel department. Specifically, by knowing: (1) the annual salary of each member in the organization, and (2) the average/annual percentage of his/her time spent on each task, one can calculate the total amount of human resources being spent on each task of the organization: defined as the actual cost per task. Further, with (1) above, and by knowing how much time members feel they should spend on organizational tasks, one can calculate the total amount of human resources that should be spent on each task according to organizational objectives: defined as the desired cost per task.

By summing all the differences on the actual vs. desired cost for each task in the organization (including all persons in the organization), suggests a measure of inefficiency or potential for productivity (Rees, 1979; Hatry, 1978; Wait, 1980). That is, the extent that actual costs are discrepant from desired costs on tasks for the organization as a whole is the amount that costs of converting inputs to outputs are misdirected. This notion of misdirected resources, it should be remembered, follows directly from the structure of the organization as defined in this paper – namely that tasks should be performed by people in line with objectives. If the actual time and costs on tasks deviates from this, then the costs of conversion have been increased by the amount of the discrepancies and, therefore, productivity has been negatively affected by this same amount.

By knowing the current assignment of members to subunits as well as the task responsibilities of each current subunit, one can calculate, for each subunit in the organization, just how much of the desired vs. actual time to be spent on tasks occurs for tasks that are outside the boundary or jurisdiction of the subunit. In other words, to what extent do people believe that they should be spending more time on tasks located in other subunits of the organization. Operationally, for each subunit, how much is desired cost greater than actual cost for tasks assigned to other subunits. This assessment totaled for all subunits would suggest the extent of a structural-interface problem. On the other hand, if the members in any subunit desire to spend even more time on tasks within their subunit’s boundary (and hence, less time outside their subunit), then a job-interface problem is suggested. Operationally, for each subunit, how much is desired cost greater than actual cost for tasks assigned to the subunit in question. When one takes all the discrepancies for each subunit and classifies these as either job-interface or structural-interface related and then sums these separately across all subunits in the organization, the total discrepancies of actual vs. desired can be partitioned into these two interfaces.

These calculations provide useful information in diagnosing an organization for: (1) the amount of overall misdirected conversion costs present, and (2) whether these misdirected resources can be recovered at the job interface (without any restructuring of subunits) or at the structural interface (requiring a restructuring of subunits). Basically, the best diagnosis an organization can hope for is to uncover a minimum amount of misdirected conversion costs, without regard from where these are derived. The next best diagnosis is to uncover a significant amount of misdirected conversion costs but to discover that these are contained largely within subunit boundaries, representing the job interface. The worst case is to uncover a significant amount of misdirected conversion costs and find that these occur across current subunit boundaries. A restructuring of subunit boundaries, therefore, would be necessary before the identified misdirected costs can be recovered by a reallocation of resources within newly formed subunits.

In essence, the more that misdirected costs are of the job-interface type, the managers or subunits are able (have the jurisdiction) to eliminate actual vs. desired time allocations on their subunit tasks. However, if the actual vs. desired discrepancies cut across subunit boundaries, managers will not be able to reduce the discrepancies very easily, if at all. As was discussed in a previous section of this paper, a subunit manager does not have the authority to request that his subordinates spend more time on tasks in some other subunit in the organization. Ordinarily, such cross-boundary discrepancies highlight division-structure problems and remain as barriers to improving productivity precisely because these inefficiencies (misdirected conversion costs) cannot be “touched” without a structural-interface change. Further, it should be evident that the discrepancies between actual vs. desired would fall mostly into the structural-interface category if the important task interdependencies have not been contained well within subunit boundaries. The more that reciprocal and sequential interdependencies are between subunits, the more that members would have indicated a desire to spend more time on tasks in other subunits so that they could accomplish organizational objectives more effectively and efficiently.

A Plan for Restructuring Subunits

A restructuring of the organization, for the purpose of better containing the important task interdependencies within subunit boundaries, is necessary for the third type of diagnostic outcome noted above – where most of the misdirected conversion costs fall within the structural-interface category. The more that a restructuring of subunits can transfer these costs from this structural interface category to the job-interface category, the more that subunit managers would be able to reallocate resources from actual to desired. The result should be a decrease in misdirected conversion costs and, hence, an increase in productivity.

From the data collection discussed earlier (member responses to the objectives and tasks dictionaries on the 7-point Likert scales), it is possible to compute a “task-containment” index for the organization’s current design of subunits, similar to the alpha coefficient of internal consistency (Cronbach, 1951). By knowing the current assignment of members to subunits as well as the particular tasks assigned to the subunits, the interrelationship of tasks within each subunit vs. between each subunit can be averaged. The index varies from 1 (where every interdependency is contained with subunit boundaries) to 0 (where every interdependency is located between subunit boundaries).

The next step is to generate an alternative design of subunits, which attempts to maximize the containment of task interdependencies, given the inter-task relationships reported by organizational members without regard to their current subunit assignments. Thus, just considering the task interrelationships, what set of subunits would provide the highest possible task-containment index? It is beyond the scope of this paper to detail the complicated and involving multivariate statistics used to generate a new structural form based on the criteria of the task-containment index (see, Kilmann, 1977). In a nutshell, however, various correlational and factor analyses can be applied on member responses to the objectives and tasks dictionaries to search out the various interdependencies and relationships among objectives, tasks, and people. These analyses can then form the subunit boundaries and the type of management hierarchy shown earlier in Fig. 1.

A task-containment index can be calculated for the new design of subunits and then compared to the task-containment index computed for the current arrangement of subunits. Given that most of the misdirected conversion costs were located in the structural-interface category, it would not be surprising to find that the new design has a substantially higher index than the current design. This result tends to reinforce the need for a new structure of subunits and supports the diagnosis of productivity problems stemming from a divisional-structure problem. In the event that the two indices (current vs. new design) are largely the same (e.g. both about 0.6), one would have to conclude that there might be other factors besides “structure” involved in generating the misdirected conversion costs, even if the latter were classified at the structural interface. Perhaps inter-unit competition is flourishing (because of a negative organization culture, an ineffective reward system, political fighting among top management, etc.) despite the fact that subunits are designed appropriately. In this case, a misallocation of resources may have been forced between subunit boundaries out of spite or for other nonrational/noneconomic reasons.

If the comparison of the task-containment indices supports the need for a restructuring (when the index for the new design is significantly higher than the current design, e.g. 0.75 vs. 0.40), then the new design provides a plan for the restructuring. For instance, by knowing the objectives, tasks, and people assigned to each subunit (as shown in Fig. 1), the organization can begin discussion on all the changes that would have to take place to move the organization from the current to the new structure of subunits. It would require too much space here to outline the full development of a plan for change including a schedule of implementation (Kilmann, 1977). However, the point is that by providing a view of what a better organization structure would be, according to the principles of task interdependencies and productivity, the organization has a viable basis for proceeding.

To help the organization assess the need for and the benefits of a structural change, one additional calculation can be suggested. Once the multivariate analyses have identified the new task assignments for each newly formed subunit, it is possible to sort the present misdirected conversion costs (actual vs. desired cost discrepancies on tasks) into the structural-interface and job-interface categories for these new subunits, just as was done for the current design of subunits. While the total amount of misdirected conversion costs remains the same, the proportion (or amount) that is sorted into the structural-interface category will be less with the new design as compared to the current design (to the extent that the task-containment index for the new design is higher than the current design). In fact, one can calculate the amount of misdirected conversion costs that have been transferred from the current structural-interface category to the new job-interface category. This amount would represent how much the new structural form can improve productivity (in dollars of savings) in contrast to the current design of subunits.

As a final note, one should not expect that the new structure, when implemented, would be identical to the one suggested by the multivariate analysis on the objectives and tasks dictionaries. Other criteria come into play besides the ones outlined in this paper, such as politics and vested interests. However, in order to enable the managers of the new subunits to recover the misdirected conversion costs, the new structure that is implemented should: (1) be better at task containment than the old design (even if it is not as good as the hypothetical design derived from the data analysis), and (2) have a reward/control system for motivating managers to bring actual costs in line with desired costs on tasks within their own subunits. Also, it can be expected that this new structure will be more conducive to developing and implementing new work methods and other aids to productivity because managers now have more autonomous subunits under their control. Thus, additional productivity improvements could be made without continually having to negotiate plans and methods across subunit boundaries.

CONCLUSION

This paper has attempted to show that the divisional structure of the organization does not have to be viewed as correct, fixed and unchangeable. Nor is it necessary to assume that the divisions are independent of one another and that divisional managers make decisions from an organization-wide perspective. Rather, it seems more reasonable to assume that the current structure may include highly interdependent divisions. While these can be redesigned to be less interdependent, the divisions in real organizations will never be completely independent.

Conceptualizing the costs of organization structure and proposing a measuring scheme to assess these costs is a way of making the above points specific and concrete. If it can be shown, first analytically and then empirically, that interdependent divisions prevent organizations from efficiently allocating peoples’ efforts on the appropriate tasks according to the right objectives, then it behooves managers and researchers to find ways to overcome this deficiency. That different divisional structures have different misdirected conversion costs (depending upon the interdependencies that are between vs. within the divisions) should help to focus more attention on the restructuring of organizations for productivity improvements.

Restructuring organizations, however, may appear to be a very radical approach to accountants who are used to leaving the existing system of organization intact. It seems that in order to improve the effectiveness and usefulness of various accounting procedures, accountants have to team up with organization designers and behavioral scientists. The same is true for any concerted effort to improve performance and productivity, presumably the primary goals of any accounting information system. But such interdisciplinary approaches are rare even if these are necessary for each profession to progress from simple to complex theories.

Hopwood (1976, p. 202), for example, has expressed his reservations about the likelihood of accountants broadening their function to include the design of formal information systems which take account of the organization’s structure: “Of course, such a reorientation would necessitate major changes in outlook and training, and in reality, I remain pessimistic about whether the profession, as distinct from some of its more informed members, is likely to change in this way. But the need is real enough. Indeed, it may be so real that one wonders whether some other group will arise to move in the direction if accountants choose not to do so.” It seems appropriate in the conclusion, therefore, to suggest some of the changes that would have to take place in accounting theory and research, if accountants did arise to the occasion.

All accounting theories and methods that necessarily involve interdivisional exchanges of information, materials, or other resources would have to allow for interdependent divisions. Even if a restructuring can remove some of the interdivisional interdependencies it is not enough for accountants to wait for all the interdependencies to be switched from between to within divisions before they proceed. Real organizations cannot be structured into purely independent divisions. Reality does not divide up so neatly and exactly. While organization designers can make for more independent divisions, interdivisional interdependencies will be present to some significant degree, nevertheless.

Consider the budgeting process for example. Budgets are used to establish objectives, guidelines, reviews and performance evaluations for each division or department in the organization. If the divisions are independent, as is usually assumed, then if each division meets its budget and performs as expected, the organization-wide objectives are likely to be achieved. If divisions are not independent, then having divisional managers judged on the basis of such a comparison of plan and result is likely to be a very frustrating and futile experience. In the case where divisions are highly interdependent, each divisional manager has to rely on effective and timely performance of other divisions to complete tasks that are not under his control, in order for him to meet his budget. It would not be much time before the budget no longer serves as a plan or guide to decision making and action but becomes, instead, a painful source of interdivisional conflict and dysfunctional behavior. Alternatively, the budget would become useless in short order, thus negating the whole time it took to establish the budget in the first place. The latter becomes just another version of misdirected conversion costs.

Assigning costs and transfer prices to divisions in order to establish valid indicators for divisional performance also become sources of conflict under conditions of interdivisional interdependencies. Widespread perceptions would exist that view the whole allocation process as either arbitrary or inconsistent. Political as opposed to economic behavior would be encouraged, as much time is spent by divisional managers in attempting to influence the outcome of these allocation-of cost and transfer-price decisions. Stated differently, the more that divisions are interdependent, the less there is a firm basis for establishing these costs and prices. The further one moves from a market mechanism, the closer one comes to a bureaucratic or political mechanism. Again, the time spent on the latter becomes a misdirected conversion cost: spending time on negotiating accounting guidelines rather than doing the primary work of the organization.

If the rewards of divisional managers are tied to divisional performance, as is recommended in most discussions of reward and control systems (Lawler & Rhode, 1976), again one confronts the difficulty created by interdependent divisions. Here, managers are being held responsible for activities and results they do not directly control and that outstep their authority and jurisdiction. Alternatively, surrogate measures are used to evaluate performance. Since these generally do not capture the whole range of activities and results, achievement of the surrogate measures are overemphasized to the exclusion of other criteria.

The challenge to these accounting problems is to recognize interdependencies across divisions and seek to incorporate these into accounting procedures. This paper has suggested ways that interdependencies can be measured and there must be other ways as well. With such assessment, it might be feasible to adjust these accounting systems to include interdependencies explicitly. Thus, rather than ignore interdivisional interdependencies, accounting systems can rely on these to develop more accurate assessments of the functioning of complex organizations. And it does seem that organizations are getting more, not less, complex. The same should be true for our theories and assumptions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrews, K. R., The Concept of Corporate Strategy (Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin, 1971).

Ansoff, H. I., Corporate Strategy: An Analytical Approach to Business Policy for Growth and Expansion (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965).

Anthony, R., Planning and Control Systems: A Framework for Analysis (Boston: Harvard, 1965).

Argyris, C., The Impact of Budgets on People (New York: Controllership Foundation, 1951).

Barnard, C. I., Functions of the Executive (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1938).

Birnberg, J. G., Turopolec. I., & Young, S. M., The Organizational Context of Accounting, Accounting, Organizations and Society, (l983) pp. 111-129.

Blake, R. R. & Mouton, J. S., Group Dynamics: Key to Decision Making (Houston: Gulf, 1961).

Blake, R. R., Shepard, H. & Mouton, J. S., Managing Intergroup Conflict in Industry (Houston, Gulf, 1954).

Chandler, A. D., Strategy and Structure (Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T., Press, 1962).

Cronbach, L. S., Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests, Psychometrika (1951), pp. 297-334.

Davis, L. W., Job Design and Productivity: A New Approach, in YukI, G. A. and Wexley, K. N. (eds.). Readings in Organizational and Industrial Psychology (New York: Oxford, 1971).

Dopuch, N, Bimberg, J. B. & Demski, J., Cost Accounting: Managerial Uses of Accounting Data,Third Edition (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch, 1982).

Evan, W., Organization Theory: Structures, Systems, and Environments (New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1976).

Hall, R. H., Organizations: Structure and Process (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1977).

Harman, H. H., Modem Factor Analysis, Revised Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1967).

Hatry, H. P, The Status of Productivity Measurement in the Public Sector, Public Administration Review (1978), pp. 28-33.

Hopwood, A., Accounting and Human Behaviour (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976).

Jehring, J. J. (ed.), Solving Problems of Productivity in a Free Society (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin, 1962).

Julian, J. W. & Perry, E. A., Cooperation Contrasted with Intra-group and Intergroup Competition, Sociometry (1967).

Katz, D. & Kahn, R. L., The Social Psychology of Organizations, 2nd edn. (New York: Wiley, 1978).

Kendrick, J., What is Productivity? In Solving Problems of Productivity in a Free Society. Jehring, J.J. (ed.). (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1962).

Kilmann, R. H., Social Systems Design: Normative Theory and the MAPS Design Technology(New York: Elsevier North Holland, 1977).

Kilmann, R. H., Pondy, L. R. & Slevin, D. P. (eds.), The Management of Organization Design: Vols. I and II (New York: Elsevier North-Holland, 1976).

Lawler, E. E. & Rhode, J. G., Information and Control in Organizations (Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear, 1976).

Lawrence, P. & Lorsch, J., Organization and Environment (Boston: Harvard, 1967)

Mackenzie, K. D., A Process Based Measure for the Degree of Hierarchy in a Group, III: Applications to Organizational Design, Journal of Enterprise Management (1978a), pp. 175-184.

Mackenzie, K. D., Organizational Structures (Arlington Heights, IL: AHM Publishing Co., 1978b).

Mackenzie, K. D., Concepts and Measures in Organization Development, Working Paper, University of Kansas, School of Business, 1981.

MacMilIian, I. C., Strategy Formulation: Political Concepts (St. Paul, MN: West, 1978).

March, J. G. & Simon, H. A., Organizations (New York: Wiley, 1958).

Meyer, M. W., Theory of Organization Structure (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977).

MiIitzer, K. H., Macro vs. Micro – Input/Output Ratios, Management Review (1980), pp. 8-15.

National Center for Productivity, Productivity in the Changing World of the 1980’s: The Final Report of the National Center for Productivity and Quality of Working Life (Washington, DC: US. Government, 1978).

Pheysey, D. C., Payne, R. L. & Puch, D. S., Influence of Structure on Organizational and Group Levels, Administrative Science Quarterly (1971), pp. 61-73.

Rees, A., Improving the Concepts and Techniques of Productivity Measurement, Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 102, No. 9 (1979), pp. 23-27.

Ridgway, V. F., Dysfunctional Consequences of Performance Measurement, Administrative Science Quarterly (1956), pp. 259-268.

Rush, H. F. M., Job Design for Motivation (New York: The Conference Board, 1971).

Schendel, D. E. & Hofer, C. W. (eds.), Strategic Management: A New View of Business Policy and Planning (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979).

Seiler, J. A., Diagnosing Interdepartmental Conflict, Harvard Business Review (1963), pp. 121-132.

Siegel, I. H., Company Productivity: Measurement for Improvement (Kalamazoo, MI: WE Upjohn Institute, 1980).

Simon, H. A., Guetzhow, H, Kozmetaky, G. & Tyndall, G., Centralization vs. Decentralization in Organizing the Controller’s Department (New York: Controllership Foundation, 1954).

Thomas, A., A Behavioral Analysis of Joint Cost Allocation and Transfer Pricing (Stipes Publishing Company, 1980).

Thomas, K. W., Conflict and Conflict Management, in The Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Dunnette, M.D. (ed.). (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1976).

Thompson, J. D., Organizations in Action (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967).

Umatot, D. D., Bell, C. H. & Mitchell, T. R., Effects of Job Enrichment and Task Goals on Satisfaction and Productivity: Implications for Job Design, Journal of Applied Psychology (1976), pp. 379- 394.

Wait, D. J., Productivity Measurement: A Management Accounting Challenge, Management Accounting (1980), pp. 24-30.