24 May The Evolution and Purpose of the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument (KOCI)

by Ralph H. Kilmann

co-author of the Thomas-Kilmann Instrument (TKI)

INTRODUCTION TO ASSESSING AND RESOLVING ORGANIZATIONAL CONFLICT

It’s a great pleasure to share with you the evolution of my work in conflict management and change management, which, of course, includes what I’ve learned from using the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument in many different situations since the early 1970s. That evolution of my work with the TKI instrument eventually led me to develop the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument almost 50 years later, which I call KOCI for short. In essence, the KOCI explicitly assesses how an organization’s systems and processes, represented by the eight tracks of quantum transformation, powerfully influence how effectively organizational members can resolve their most challenging conflicts and problems.

But before I share more about the KOCI assessment tool, let me put my work on conflict management in a historical perspective, which will convey why it became so necessary for me (hence, the driving “purpose”) to explicitly assess how members approach—and attempt to resolve—their systems conflicts.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE THOMAS-KILMANN CONFLICT MODE INSTRUMENT (TKI)

Way back in the early 1970s, Ken Thomas and I developed the TKI to assess how individuals respond to interpersonal conflicts in general, without specifying any particular situation. In fact, here are the standard TKI instructions that are printed on every TKI paper booklet…and these same exact instructions are also shown on your computer or mobile screen when you take the online version of the TKI assessment tool:

“Consider situations in which you find your wishes differing from those of another person. How do you usually respond to such situations?”

The respondent is then shown 30 pairs of statements that describe different behavioral responses to any interpersonal conflict. For each pair of A/B choices, the person is asked to select the statement that best characterizes his or her behavior, which represent those five different conflict-handling modes: collaborating, competing, compromising, and so forth. After a person completes her responses to these 30 items, the results reveal which conflict modes that person might be using too much or too little, as compared to a large normative sample.

It’s important to re-emphasize this key point: Respondents to the TKI are NOT presented with any specific interpersonal situation. Instead, respondents are asked to provide their typical responses to conflict across ALL such situations. In fact, when a trainer or facilitator reviews the TKI’s instructions for a group of participants, there is always someone in the audience who asks this question: “Since I respond to conflict differently, depending if I’m at home or at work, which setting should I keep in mind while responding to the items on this instrument?”

The facilitator who’s administering the TKI to these participants is expected to provide this standardized answer: “Don’t think of any particular situation when you respond to the 30 items on the TKI. Just provide your typical response, your average response to conflict, across all the situations in your life.”

By 1974, just before the TKI was officially published, Ken and I already knew that some people had a little difficulty responding to the TKI by mentally averaging, so to speak, their typical response to conflicts across all situations, rather than focusing only on their behavior in the workplace or focusing only on their behavior in their home with family or friends, or in some other specified social setting. But despite this dilemma, we still worded the TKI instructions to illicit the typical or average behavioral response a person has to interpersonal conflict in general—since our exclusive use of the TKI at that time (as young assistant professors) was in teaching college students who either were unemployed or held jobs in altogether different organizations.

Modifying the Standard TKI Instructions for a Specific Conflict Situation

By the late 1970s, I became regularly involved in conducting management training workshops and implementing various consulting programs INSIDE organizations. Not surprisingly, I made considerable use of the TKI assessment, since almost everyone needed to be more comfortable with conflict and also learn how to manage workplace conflict much more effectively.

I don’t recall exactly when I first tried modifying the TKI for a specific conflict situation, but I began experimenting with modifying the TKI’s standard instructions so that member responses to the assessment would be specific to how conflicts were being addressed INSIDE the organization. So instead of using the standard TKI instructions, which implicitly ask people to consider ALL situations in their life, I began asking participants to respond to the TKI’s 30 A/B items along these lines:

“In this organization, or in this group, or in this department… how do you usually respond when you find your wishes differing from those of other members?”

When I modified the TKI instructions in this manner, respondents never again asked me whether they should respond to the TKI in terms of their conflict experiences at home or at work. I had now provided them with a specific situation that they could easily keep straight in their mind as they responded to all 30 A/B items on the TKI assessment tool.

Using Two TKI Assessments—Each with Modified Instructions—To Explore the INSIDE and OUTSIDE Organizational Perspective

After having modified the standard TKI instructions for many organizations and work situations in the 1970s and 1980s, by the early 1990s, it occurred to me to ask each member to take TWO TKIs, each with modified instructions. This approach seemed pretty radical at the time, but revealed some very valuable information that one TKI, by itself, could never provide.

To make a long story short, when I conduct management training programs or provide consulting services to an intact group or organization, I ask the members to take their first TKI from the perspective of INSIDE their group, department, or organization (however they wish to focus on conflict at work), and then, right afterwards, I ask those same members to take a second TKI from the perspective of OUTSIDE their group (meaning, how they respond to conflict in all other settings of their life, excluding their current group or department). In essence, this second TKI is much like the original TKI, since it asks respondents to provide their typical, average responses to conflict across many different settings and situations.

Basically, the second TKI asks respondents to provide their “average” or their typical approach to conflict across all those other situations, which necessarily includes conflicts with their family members, friends, neighbors, other organizations, and so forth. Naturally, there will always be some personal preferences at play when an individual chooses to use one conflict mode or another, based on psychological type or style.

In sharp contrast to the OUTSIDE perspective, when participants focus on their conflict-handling behavior INSIDE their group, team, or organization, there are various systems and processes in an organization that tend to encourage or require members to use certain conflict modes more than others, in contrast to what modes these members typically use across all the other settings in their life.

Incidentally, I expect that the culture of the organization as a whole as well as the specific cultural variations within any particular work group can significantly influence the choice of conflict modes, especially when there are cultural norms along the lines of don’t disagree with your boss, don’t make waves, don’t rock the boat, keep your new ideas to yourself, don’t share information with other groups, and so on.

In a similar vein, through various experiences with their organization’s reward systems, members might also have learned that it’s best not to use the more assertive modes, since that behavior could hurt their chances for promotion, if obedience and loyalty are rewarded more favorably than candor and integrity.

In the same organization, the leaders might also be inclined to publically announce their decisions to members in a rather assertive and authoritative manner, which might compel members to silently accommodate their boss’s views… or group members might simply avoid challenging their managers during any conversation or group meeting.

As in the case of the outside perspective, with respect to the inside perspective, the personal preferences of members can also shape how they approach their conflicts inside their group, since some members, for example, might be more introverted than others and thus might be more inclined to keep their opinions to themselves. As we’ll see in a little while, however, the organization’s systems and processes tend to have, by far, the greatest influence in shifting the OUTSIDE TKI results to different INSIDE TKI results, while individual preferences tend to have a relatively minor influence in the choice and use of conflict modes in the workplace.

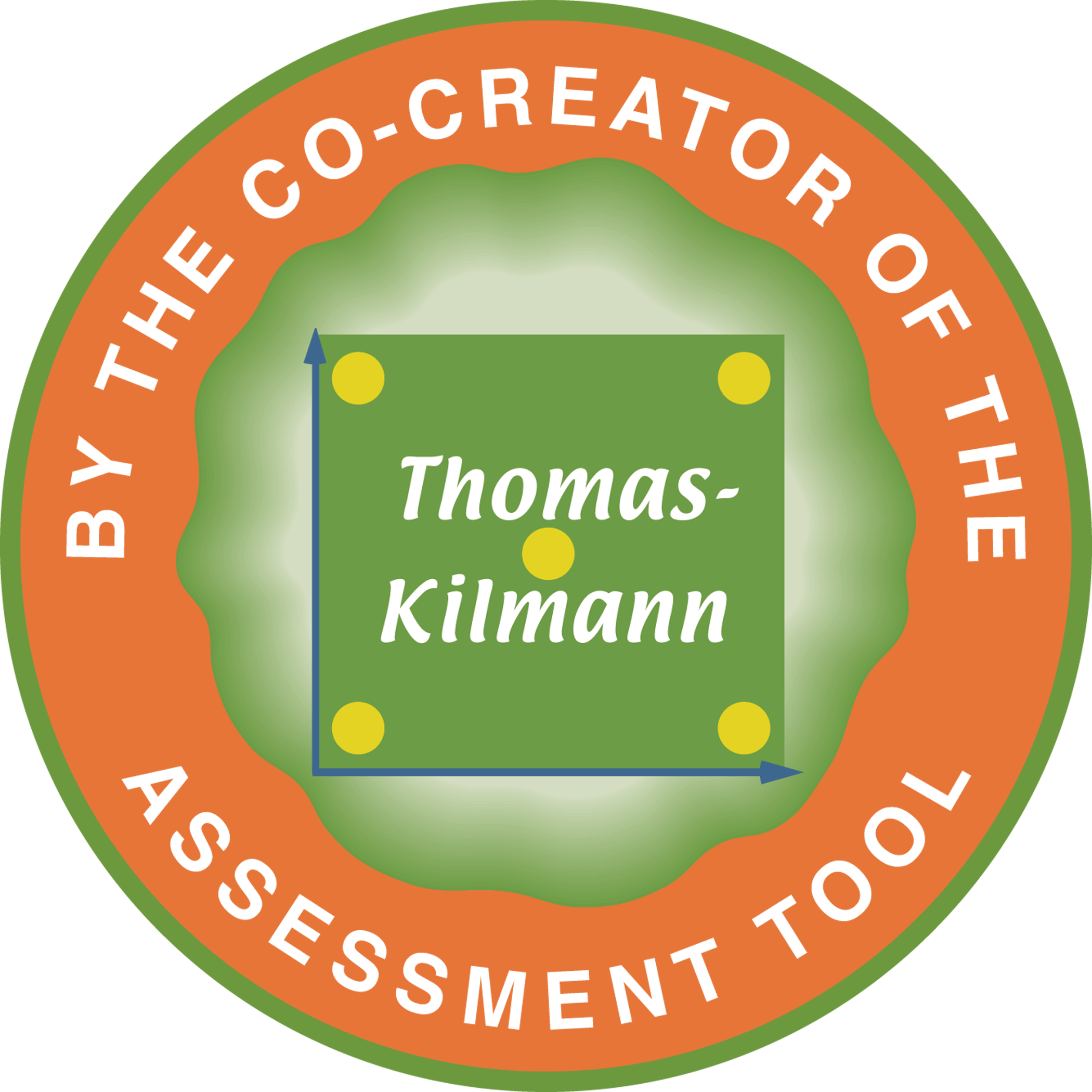

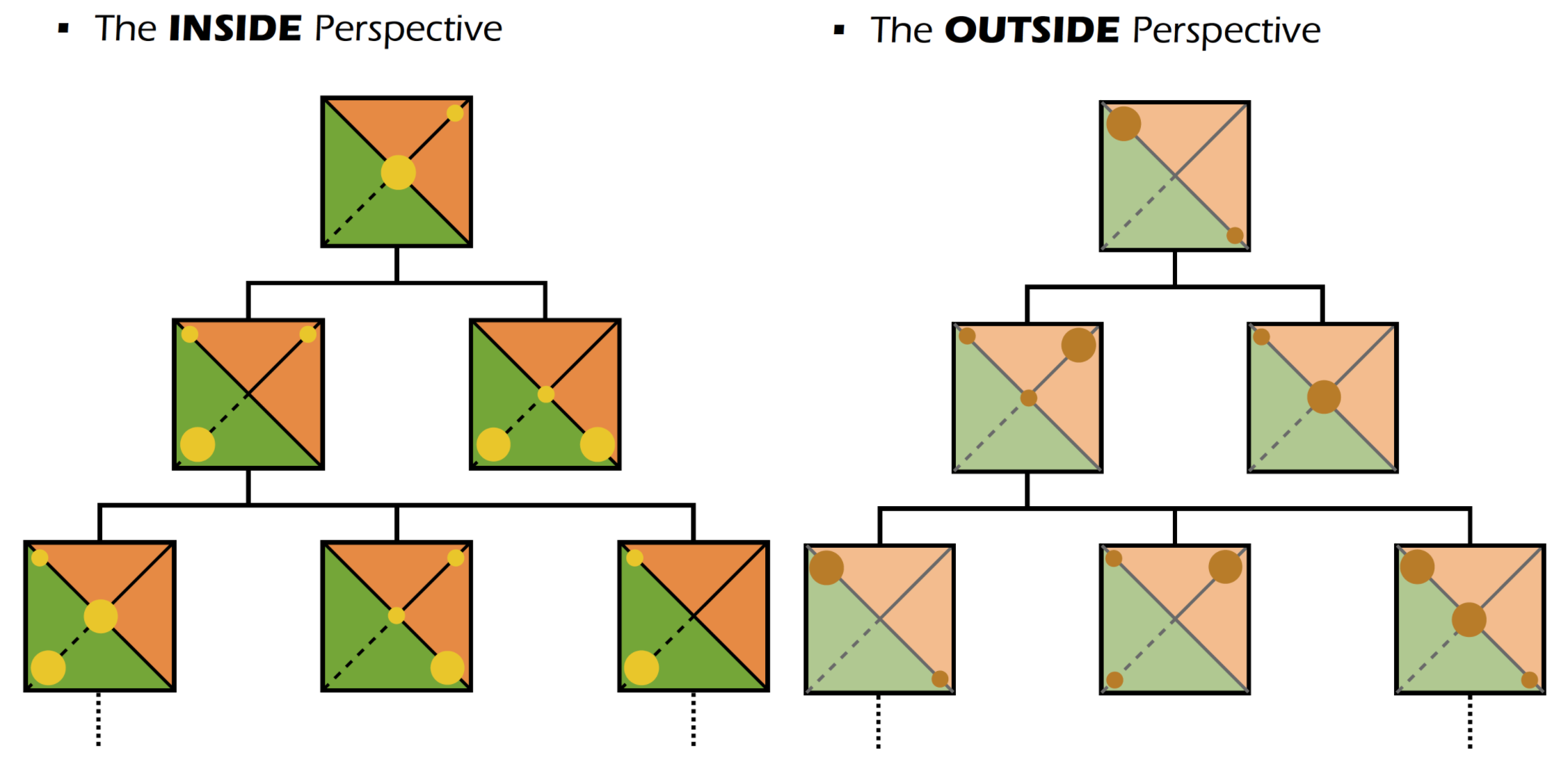

So what did I learn by having participants take two TKIs, each with modified instructions for the INSIDE and the OUTSIDE perspective? The diagram below shows one way of answering that question: Here we see a symbolic organization chart, with the senior executives at the very top of the hierarchy, the next level of managers right below them, followed by the next level of managers or non-supervisory personnel, and so forth. Naturally, large organizations have many more levels, divisions, and groups, but this simplified organization chart is sufficient for our purposes.

The above figure shows the symbolic organization chart from the INSIDE perspective, which is based on member responses to their first TKI for INSIDE your group, inside your department, or INSIDE your organization.

As you can see, I have found it especially useful to replace each box on the organization chart, which represents a division, department or workgroup, with the TKI Conflict Model, which then conveniently highlights the particular conflict modes that are being used most often—as shown by the large circles where a conflict mode is positioned on the TKI Conflict Model. At the same time, each box on the chart also highlights the conflict modes that are being used least often—as shown by the very small circles on the TKI Conflict Model. For the sake of simplicity and convenience, the conflict modes that are being used moderately are not explicitly designated by any symbol on the TKI Conflict Model. Instead, focusing primarily on those conflict modes that each group or department is possibly using too much or too little tends to provide the most concise information in a visually clear-cut manner.

On this organizational chart, notice that the executives on top of the hierarchy are primarily using the compromising mode, which is moderately assertive, while the next two levels are primarily using the avoiding and accommodating modes, which are the most unassertive modes. What is displayed on this chart is, in fact, a rather typical result, revealing the overuse of avoiding and accommodating as we move farther down the organization’s hierarchy. In fact, it is not unusual to find that the executives at the top of the hierarchy use lots of competing, compromising, and collaborating to address their conflicts inside the organization, while the employees toward the bottom of the hierarchy use lots of avoiding and accommodating to comply with the bosses and managers above them.

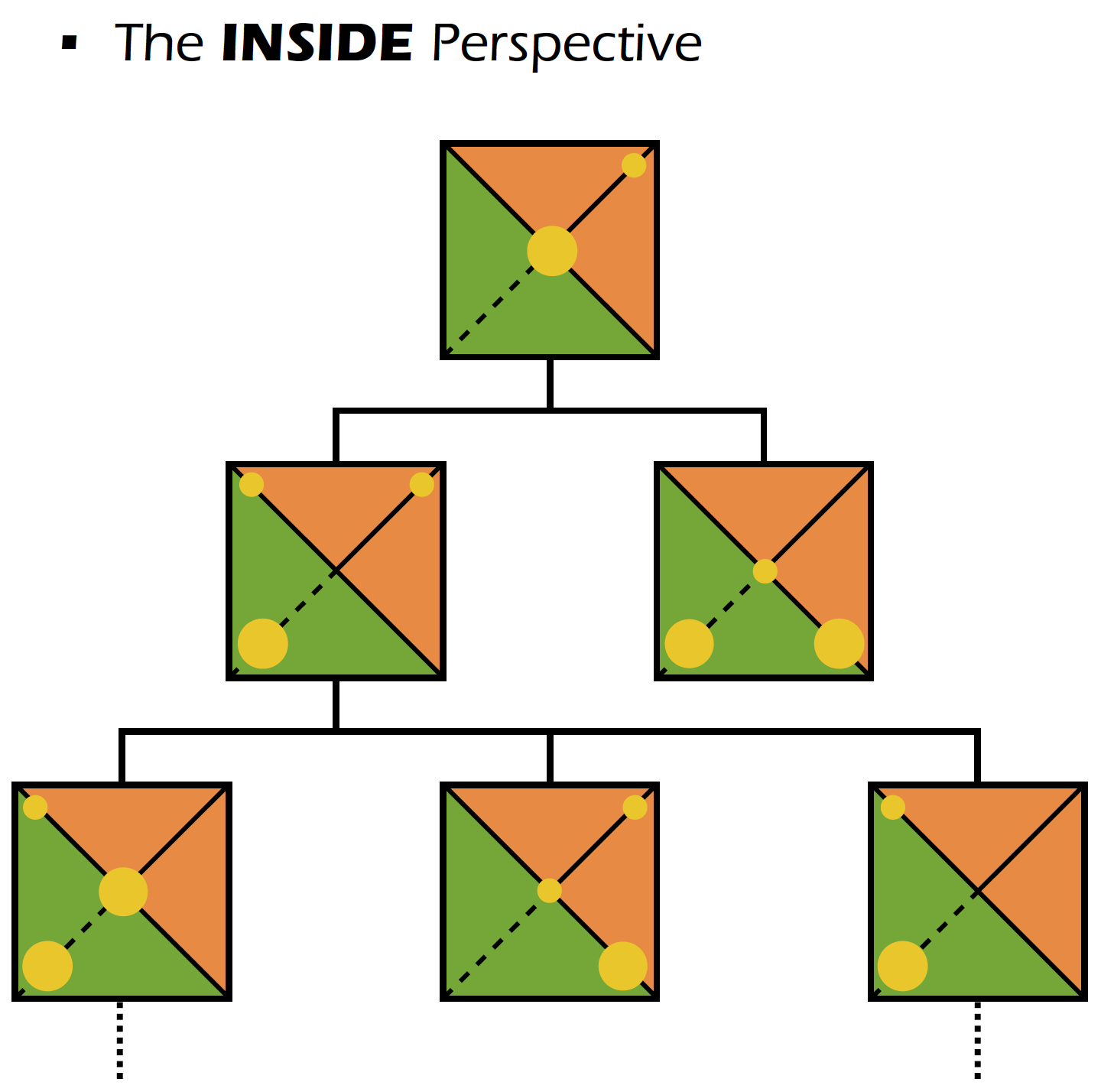

On this next figure, the TKI results displayed on each box on the organization chart derives from the OUTSIDE perspective, meaning that these results were based on members’ responses to their SECOND TKI, with the modified instructions to assess their conflict-handling behavior OUTSIDE their group or organization. As you can see, the more assertive modes are frequently being used outside the organization, and, most striking, this same pattern of conflict-handling behavior emerges up and down the management hierarchy and this pattern is also the same as we look across the various departments and groups at the same level in the organization. Said different, every box on the organization chart shows that members are rather assertive when they approach a conflict situation OUTSIDE the work setting, as revealed by the frequently used modes of competing, collaborating, and compromising across this entire organization chart.

Now take a quick back-and-forth look between the INSIDE and OUTSIDE perspective, as vividly portrayed by the two—side-by-side—organization charts reproduced below. Sometimes, the INSIDE and OUTSIDE charts are very similar for an organization. But most of the time, the two charts are pretty different, which typically reveals that the avoiding and accommodating modes are being used more frequently INSIDE the organization as you move from the senior executive level at the top of the chart, down the hierarchy, to the front-line employees at the bottom of the chart:

But I must now confess: Although I have already itemized the several PROBABLE causes of any large discrepancies between the inside and outside perspective, such as the organization’s culture, the group’s culture, the reward system, and the leader’s behavior (which are collectively referred to as the organization’s systems and processes), technically speaking, my list of probable causes for the differences in the INSIDE and OUTSIDE perspectives is only a guess, even if it’s a good guess based on my knowledge of organizational behavior, since those two TKI assessments are only measuring conflict-handling behavior inside and outside the group. Let me be crystal clear: The TKI only measures conflict-handling behavior. That’s it. The TKI does NOT measure anything having to do with the systems and processes in an organization, and what impact each of those systems and processes is having on conflict-handling behavior.

More specifically: Even if the culture, reward system, and leadership behavior are the principle causes for any observable differences between the inside and outside charts, we still don’t know the relative influence of an organization’s different systems and processes. Are all of these aspects of the organization playing an equal role in shifting members’ conflict-handling behavior, or is the culture the chief culprit… or is it the reward system that compels members to use some modes more than others… or are members more likely to use avoiding and accommodating at the lower levels in the organization largely due to very assertive, authoritative bosses and leaders?

Again, even using two TKI assessments per person, it is anybody’s guess as to what particular systems and processes are causing members to use certain conflict modes to address their workplace conflicts, which may or may not be effective or desirable.

What’s the BOTTOM LINE here? I can’t emphasize this important point enough: The TKI only measures conflict-handling behavior in interpersonal settings… it does not measure anything about systems and processes. As a result, to go beyond mere guesses as to why people are approaching conflict differently whether they’re inside or outside their organization, we have to find a way to measure the impact of systems and processes directly and explicitly and, of course, accurately.

The Complex Hologram:

Illuminating an Organization’s Systems and Processes

Before I introduce my Organizational Conflict Instrument and how it explicitly measures the systems and processes in organizations that could be negatively affecting how conflicts are being addressed and resolved, I will first be more specific about what I mean by an organization’s systems and processes, and why these systems and processes have such a powerful impact on how members approach their workplace conflicts… which might be very different from how members approach conflicts in all the other settings in their life.

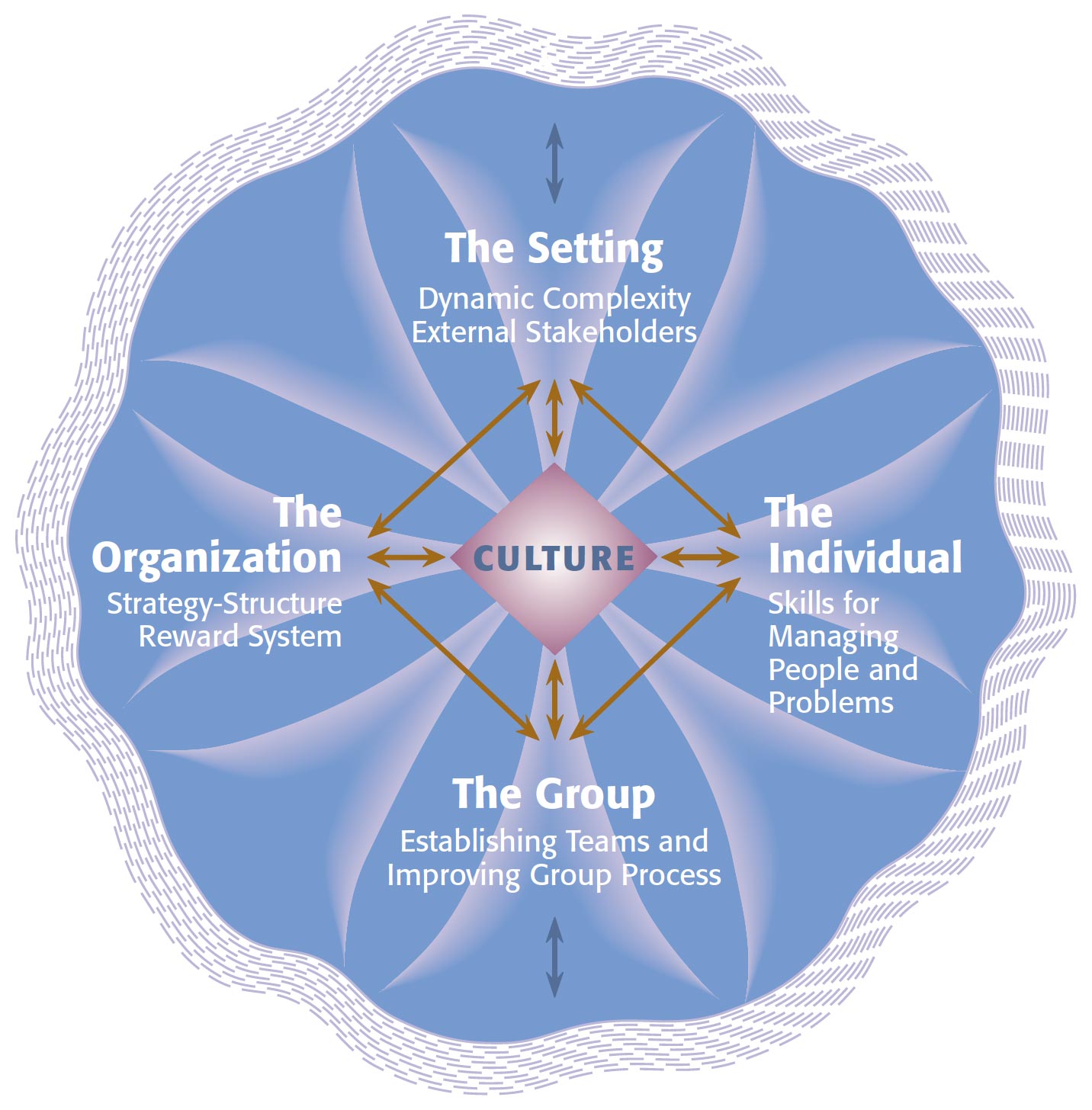

On the next figure, I present the Big Picture of all aspects of life in an organization, also called the Complex Hologram, which presents the major topics of organizational behavior that have been studied for ages. I developed the first version of this model back in the late 1970s and then published it in my 1984 book: Beyond the Quick Fix.

Very briefly, on the right side of the Complex Hologram, we can represent all the individuals that are members of the organization—particularly taking note of their individual styles and skills for addressing problems and conflicts. These individuals are officially surrounded by, and thus guided by, the organization’s culture, strategy, structure, reward systems, and the immediate work group, which includes, in most cases, a boss or manager. Of course, other organizations and institutions, labeled as “The Setting” on the top of the Complex Hologram, surround the organization itself and make up its external environment. These “External Stakeholders” also affect the kinds of problems and conflicts that members face on a daily basis.

All in all, the various NODES in Complex Hologram represent the organization’s informal and formal systems (culture, strategy, structure, rewards, groups, and individual skills and styles for managing people and problems). Meanwhile, all the double arrows that are IN BETWEEN these various system nodes represent all the business, management, and learning processes that flow throughout the organization, which include all the tasks, decisions, and actions, which, in essence, include all work-related activities that take place over time… which is exactly what defines any kind of process.

I now present the first key principle that derives from the Complex Hologram and thus underscores my inspiration for developing the Organizational Conflict Instrument: Because this key principle is so relevant to life in organizations, I highlight it in bold:

About 80% (or more) of what goes on in an organization is determined by its systems and processes, while only 20% (or less) is determined by member desires or preferences.

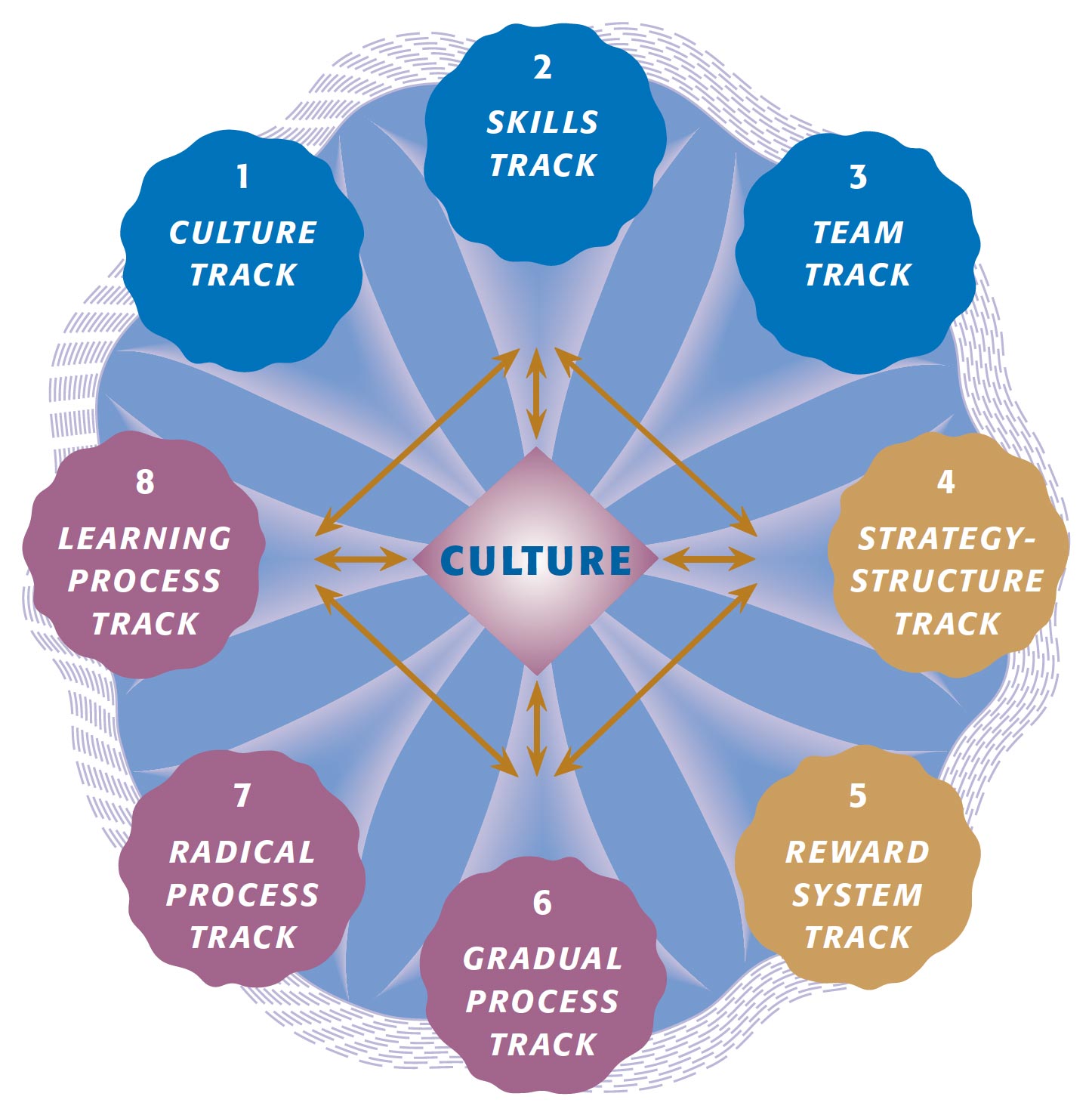

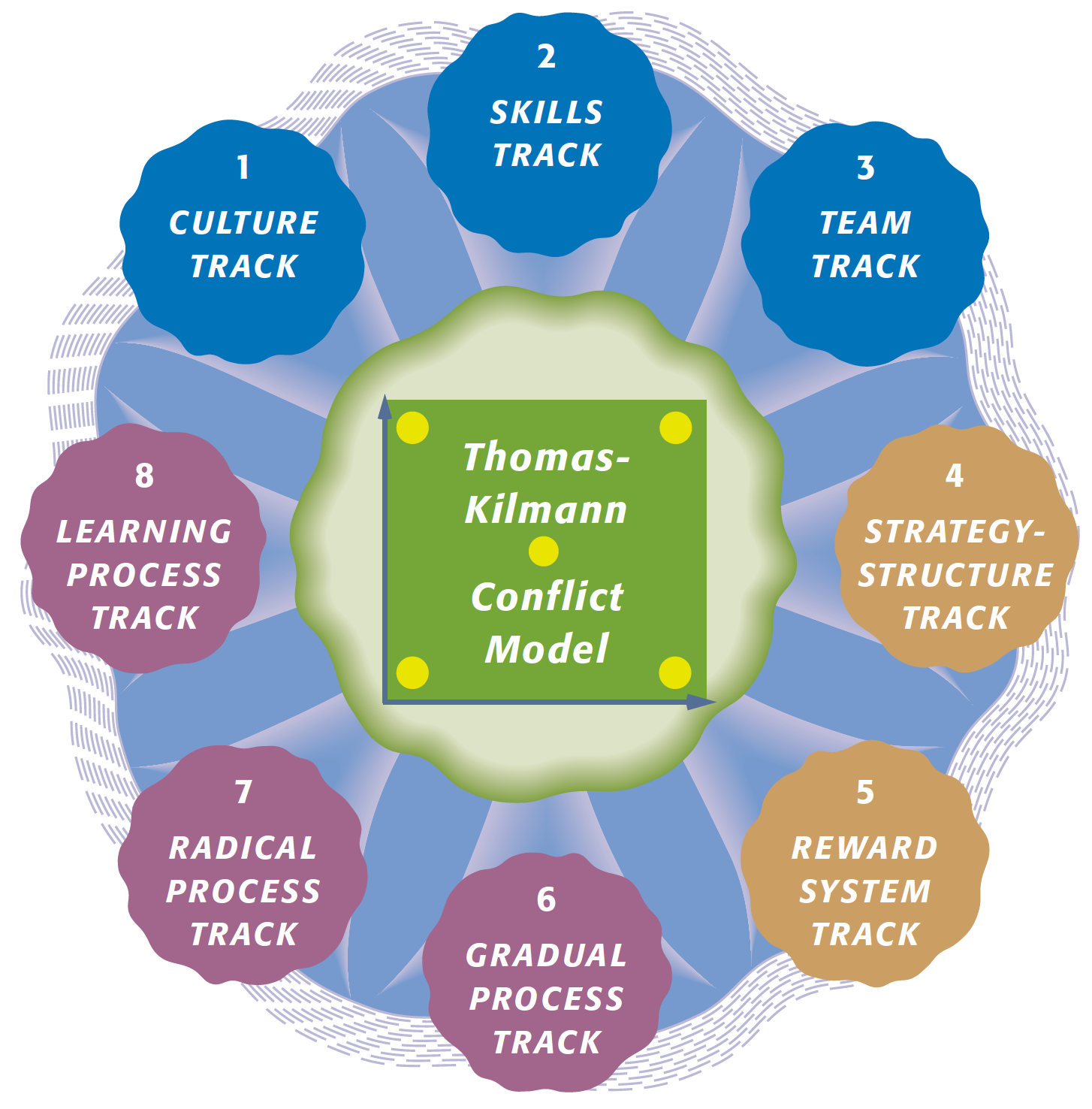

Based on my 2001 book, Quantum Organizations, below I provide an even more elaborate model that captures how a completely integrated program of eight tracks can identify and resolve the potential problems and conflicts that are highlighted in the Complex Hologram, which, as we saw before, represents all the systems, processes, and individuals in an organization, including its External Setting, which can dramatically affect which particular conflict modes members choose and use INSIDE their organization.

The first three tracks in the sequence of eight tracks represent the quantum infrastructure, also called the informal organization, which considers how well the culture, skills, and teams support long-term organizational success. The next two tracks address the formal systems, which are usually written down on paper or are available in electronic files: Where are we headed (which is termed strategy)? How can we organize all our resources to get there (which is termed structure)? And what do we receive for helping out (which is termed rewards)? The last three tracks then enable members to improve the quality and speed of their key processes (decisions and actions that take place over time), as guided by their quantum infrastructure and their formal systems.

What is the principle behind this elaborate sequence of quantum transformation? Each track establishes the foundation for achieving the full potential of each subsequent track.

Alternatively, implementing a track OUT of sequence will make it exceedingly difficult to achieve what each track is capable of providing for the organization and its members. For example, trying to renew the strategy-structure of the organization when the culture discourages members from expressing their true beliefs and feelings in the presence of bosses or managers will undermine any discussion of strategy-structure and will therefore prevent any new strategy-structure document on paper from actually guiding member behavior on the job. The same logic applies to any other out-of-sequence applications of one or more tracks to quantum transformation.

The Quantum Wheel:

Change Management and Conflict Management

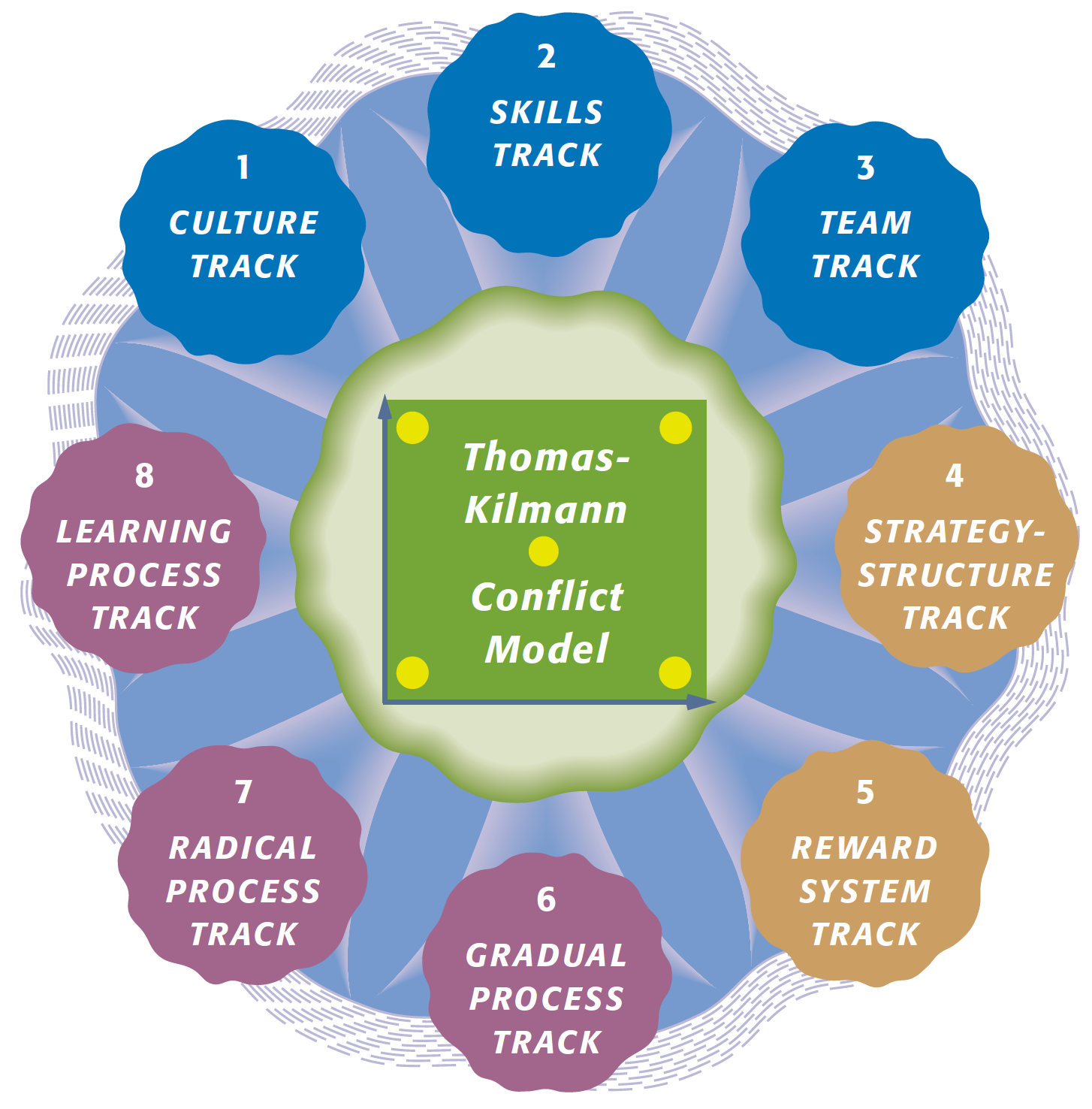

Below is another elaborate model, called the Quantum Wheel, which integrates my work on both conflict management and change management. As captured in this panoramic diagram, while the HUB of “The Quantum Wheel” is conflict management (represented by the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Model), the outer ring or spokes of “The Quantum Wheel” are the eight tracks for achieving long-term organizational success and personal meaning. But for all five conflict-handling modes to be fully available to the membership, the organization’s systems and processes must first create “the right conditions” for effectively using each conflict mode as intended.

And what are the right conditions? The systems and processes that surround each individual must actively allow and support the use of all five conflict-handling modes, so organizational members can choose and use the most effective mode, depending on the key attributes of the situation.

If the surrounding systems and processes only allow the members to use the accommodating mode or the avoiding mode, because members don’t feel safe in asserting themselves in the workplace, they won’t be able to improve their systems and processes. At the same time, the members won’t be able to effectively address and resolve all their other business and technical problems if they don’t feel comfortable or safe in asserting their knowledge, wisdom, and experience in front of others in the organization.

It’s so important that you appreciate this key point: It takes supportive and fully aligned systems and processes for members to not only use all five conflict modes, depending on the key attributes of the situation, but also to use the appropriate conflict modes for successfully addressing all the organization’s business, technical, and management problems. Basically, for the organization to succeed both short term and long term, its systems and processes must actively support effective conflict management for its most important problems and conflicts.

When Is It Best to Use Each Available Conflict Assessment Option?

Given the several choices that are now available for assessing conflict-handling behavior, it’s not surprising that I’m often asked to help people decide when it’s best to use each available assessment tool. Specifically, I am often asked two basic questions. The first type of question is simply this: “When is it best to use 1 TKI per person with those STANDARD TKI instructions…OR…when is it best to use 1 TKI with MODIFIED instructions for INSIDE your group? The second type of question is along these lines: When is it best to use two TKIs per person, each with the modified instructions for INSIDE and OUTSIDE your group…OR…when is it best to use the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument instead of either 1 or 2 TKIs per person?

Regarding the first type of question, having each participant take 1 TKI with those standard TKI instructions is still the best choice when teaching students or conducting training programs when the respondents are either not employed or come from different organizations. This use of that 1 standard TKI per person helps respondents learn more about their conflict-handling behavior across all their interpersonal encounters, since there’s no immediate interest in learning about their behavior in any specific work or family setting.

However, when the participants all come from the same intact group or intact organization and the focus of the training is on conflict-handling behavior in that particular team or organizational setting, that’s the time to modify the standard TKI instructions to a focus on “inside your group” in order to make the assessment more accurate for that specific group or organization—and thus not to dilute the results by members possibly thinking about other situations as they respond to the TKI, which they might be prone to do if they are given the TKI’s standard instructions.

Regarding the second type of question that I’m often asked, in those cases when the consultant or trainer wants to know the overall—general—effect of an organization’s systems and processes on members’ conflict-handling behavior, it’s then a good idea to consider asking members to take two TKIs per person, so it becomes possible to discover if members are using different conflict modes INSIDE versus OUTSIDE their group or organization.

But as I’ve stressed earlier, although the two TKIs provide a general impression, an educated guess, about whether or not the organization’s systems and processes, as a whole, are having a negative influence on members’ conflict-handling behavior, asking members to take two TKIs per person with modified instructions cannot possibly provide any specific information about WHICH particular systems and processes are negatively affecting members…and WHICH particular systems and processes are, in fact, positively inspiring members to do their very best.

As a result, when consultants, trainer, and facilitators want to know which particular—specific—systems conflicts are negatively affecting members’ performance and satisfaction, it’s only by having members take the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument that it’s possible to obtain accurate information about which specific systems and processes might be undermining the available talent, knowledge, experience, and passion in the organization.

THE KOCI INSTRUMENT FOR ASSESSING ORGANIZATIONAL CONFLICT

Now that I have provided a rather detailed summary of my efforts to measure conflict-handling behavior in organizations, including my work on change management and quantum transformation, you’ll be able to fully appreciate what the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument can do for organizations and members.

First, I will summarize the two parts of the instrument and I’ll then show the kind of diagnostic information that this instrument reveals, which can then inspire the organization to implement some version of the eight tracks in order to resolve any identified systems conflicts that can get in the way of long-term organizational success and personal meaning.

For Part 1 of this instrument, you’re asked to respond to 27 systems conflicts that derive explicitly from the Complex Hologram. By the way, I purposely constructed separate items for strategy and structure, since each of these two formal systems is so important in its own right as a guide to member behavior. Later, however, these two formal systems will be combined into one strategy-structure category, since structure is always needed to implement strategy, which conveniently corresponds to the strategy-structure track.

More specifically, for Part 1 of the Organizational Conflict Instrument, you are asked to indicate how often you are negatively affected by each of the “systems conflicts” on the instrument by selecting your response on a five-point scale: (1) when you are never affected negatively by that systems conflict; (2) when you are rarely affected negatively by that systems conflict; (3) when you are occasionally affected negatively; (4) when you are frequently affected negatively; and (5) when you are always being negatively affected by that systems conflict.

So you can get a sense what is meant by a systems conflict, here is an item from Part 1 of the instrument concerning the structure of the organization: “I have neither the necessary authority nor the sufficient resources to achieve my assigned goals and objectives, yet I’m held accountable for the results.”

And here is a systems conflict regarding teams in the organization: “During meetings, some members are more reserved than others, but no one makes a special effort to ask those quieter members to express their opinions or ideas.”

Essentially, Part 1 of the Organizational Conflict Instrument explicitly—and directly—measures which particular systems conflicts might be limiting your choice of the conflict modes you can comfortably and safely use inside your group or organization, which might be very different from the ease and comfort you experience in using those same conflict modes OUTSIDE your group or organization. Thus Part 1 explicitly assesses what the results from two TKIs per person can only infer… which, at best, is just an educated guess, but members taking two TKIs each still does not allow anyone to pinpoint which one or a few systems conflicts are having the largest negative influence on organizational members.

Here are the instructions for Part 2 of the instrument: For each of the nine systems conflicts (treating strategy and structure separately for the time being), you’re asked to indicate your relative use of the five conflict-handling modes, by arranging five statements from 1 to 5, where the statement you would drag into the #1 position is the conflict mode you used most often in approaching—or trying to resolve—that particular kind of systems conflict. Then, you would drag the statement representing your next used approach to that systems conflict into the #2 position, and so forth, eventually dragging your least used conflict mode into the #5 position. We then ask you to review how you arranged the five statements into position #1 through #5, to make sure the ordering of five statement reflects your relative tendency to approach that kind of systems conflict in your group or organization.

Although this instrument is measuring the same five classic conflict modes as the TKI, the Organizational Conflict Instrument wants you to think of those specific systems conflicts and how you tend to approach them, which is very different than simply responding to the TKI according to how you approach interpersonal conflict inside your organization. But for the Organizational Conflict Instrument, I want respondents to be very specific about how they approach their systems conflicts, so they don’t dilute their results by lumping together ALL the conflicts that they experience at work.

Once again, the focus on this instrument is precisely what has been neglected in the TKI and also neglected with all other measures of organizational conflict: If the systems and processes largely determine how people approach their conflicts and problems in organizations, let’s ask them explicitly, so we don’t have to guess or infer about the negative effects of each of those systems conflicts—nor do we have to assume, or pretend, that each of the systems conflicts is always equal in its negative effect on organizational members. In fact, a few systems can be functioning well, while others are quite dysfunctional.

In case you’re wondering, I word the conflict modes on Part 2 of instrument very differently from the way in which the TKI’s 30 items are worded.

In particular, the avoiding mode is always worded by this same description for each of the nine systems conflicts: “Sometimes, it’s simply not worth the extra time and effort it would take to discuss and examine this particular aspect of the organization, since we’re unlikely to find a good solution.”

Similarly, the collaborating mode is always worded by this same description for each of the nine systems conflicts “I always ask my boss or team members to take the necessary time to thoroughly discuss this particular aspect of the organization, so we can develop a creative solution.” The three other conflict modes, completing, compromising, and accommodating, are also worded in terms of addressing systems conflicts in organizations—not interpersonal conflict in general (which is the prime focus of the TKI assessment).

Regarding how the systems conflicts are worded on Part 2 of the instrument, I can provide two examples. Here is the systems conflict between the organization’s reward system and its individual members: “How are you likely to respond when you experience the negative aspects of your organization’s REWARDS—regarding the design and functioning of the performance appraisal system?” For this item, you would arrange those five statements into positions 1 through 5 to reflect your relative tendencies to use those conflict modes to approach your reward systems conflicts.

As a second example of the items from Part 2, here is another conflict that can occur between systems and individuals: “How are you likely to respond when you experience the negative aspects of TEAMS—regarding how meetings are conducted and whether the boss makes sure that all the wisdom in the group is used for its major decisions?”

For this item, you would arrange those same five statements into positions 1 through 5 to reflect your relative tendencies to use those conflict modes to approach your team conflicts. You would then do the same for the remaining items in Part 2 of the Organizational Conflict Instrument.

Interpreting an Individual’s KOCI Results:

BEFORE and AFTER the Eight Tracks

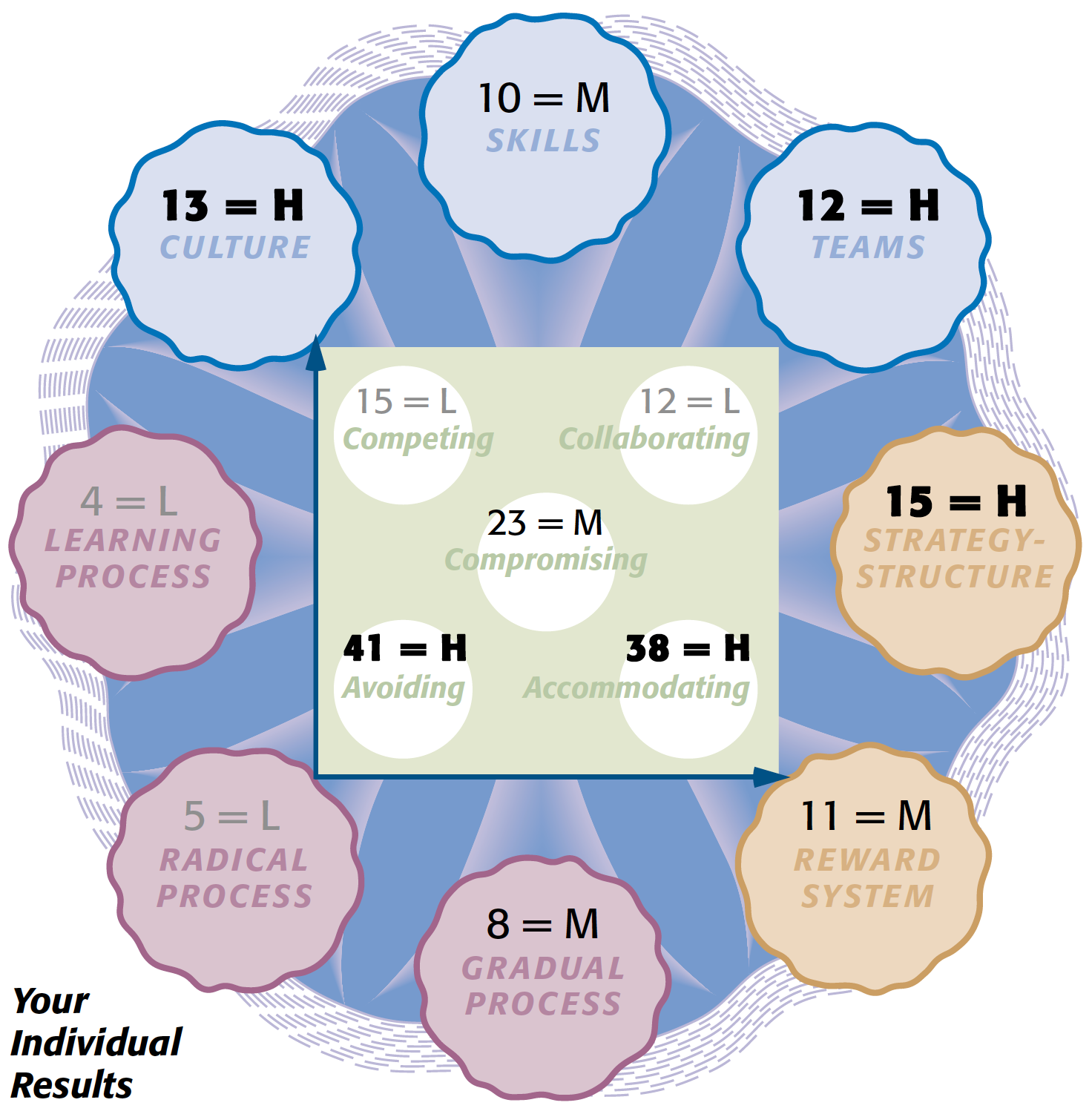

Let’s now interpret the actual results for an individual: As seen in the figure below, the raw scores for the systems conflicts are placed in the outer ring of the Quantum Wheel, including which ones are H, M, and L, as based on the established ranges for High, Medium, and Low, which are provided in the instrument’s interpretive materials.

As you can see on the above figure, there are three systems conflicts that scored in the HIGH range, which suggests that this respondent to the instrument is frequently being hampered by negative experiences with the culture of her organization or group, the way in which her team’s meetings are being conducted, and the lack of clarity and alignment in strategy-structure. These three high scores suggest some very serious barriers to long-term organizational success.

Three other conflicts are medium in their impact, since they are occasionally interfering with the person’s performance and satisfaction: skills, the reward system, and the processes that flow within her group. Yet two systems conflicts are LOW in their impact, shown by the grayed letter L: radical process and learning process improvement. But not until those earlier organizational conflicts are resolved might the last two process tracks become more challenging.

In the HUB of that same Quantum Wheel, you can also see the person’s results on the TKI Conflict Model, which shows that avoiding and accommodating are in the HIGH range. As a result, this person is almost always being negatively affected by cultural norms and team dynamics that seem to pressure members to remain quiet, not to express different points of view, and not to disagree with the boss (that is, to avoid such conflicts); or, alternatively, to defer to the experience of other members or managers, which means to accommodate others when considering how to improve the formal systems in the organization.

Indeed, the assertive modes of competing and collaborating are in the LOW range, which confirms that this person is not bringing all her talent, wisdom, ideas, and experience into the workplace. However, once the eight tracks are underway, members will be given the chance to learn more about how and when to use the five conflict modes, and especially how to change the informal systems regarding their culture, skills, and teams, so all five modes are always available to all members—and will be used successfully, as needed.

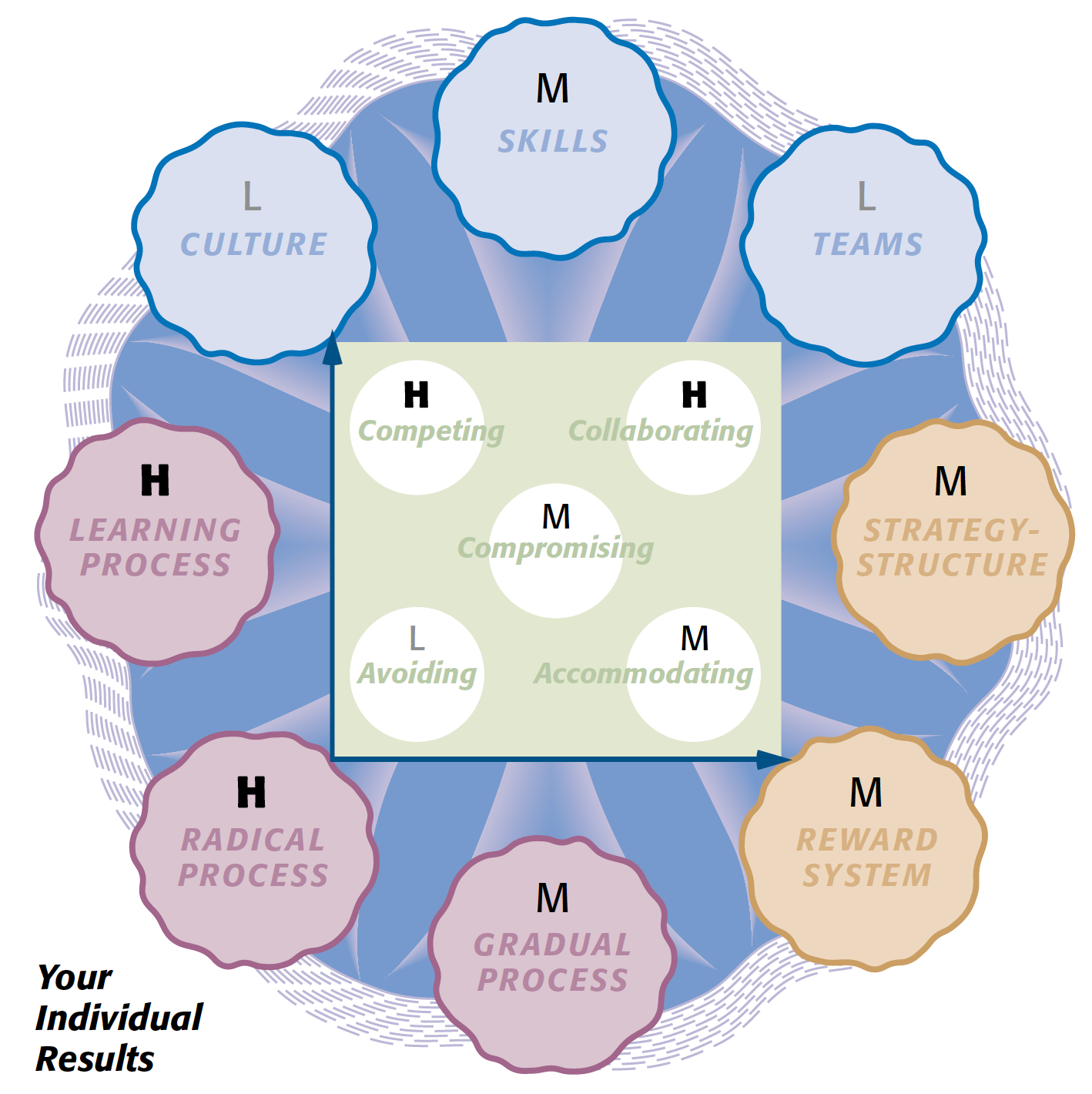

As shown on the next figure, let’s interpret the results for the same individual after she took the Organizational Conflict Instrument a second time—roughly nine months later. This time, only the H, M, and L are displayed—which makes it visually easy to immediately focus on the key systems conflicts: These results suggest that the integrated program of eight tracks has been proceeding—since the culture, skills, and teams are no longer frequently distracting this member, although more skill development might still be needed. Progress is also occurring for strategy-structure and the reward system, which sets the stage for resolving the conflicts in the last three process tracks of quantum transformation.

In the hub of this Quantum Wheel, you can also review the nine-month follow-up results on the TKI Conflict Model: The assertive modes are now HIGH while avoiding is LOW, so the “pendulum” has obviously swung from unassertive (from the prior graph) to highly assertive (using lots of competing and collaborating behavior). Usually, before the results display a balanced TKI profile (which is revealed by the presence of mostly medium scores on the five conflict modes), members go from the extreme use of a few modes to the extreme use of the other modes!

Interpreting a Group’s KOCI Results:

BEFORE the Eight Tracks

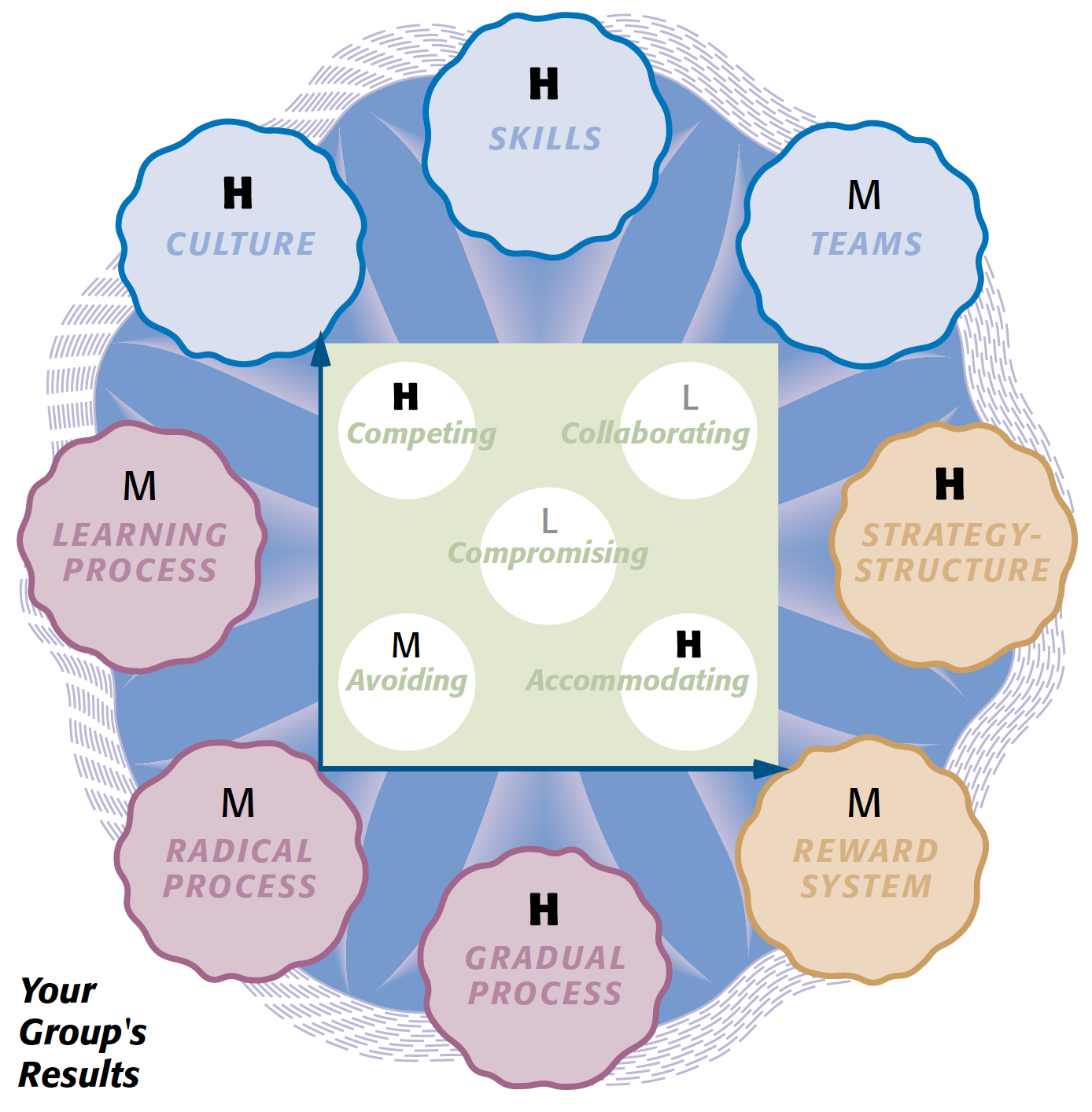

The next figure displays the key results for a twelve-member group in a large organization. Such a graph can be developed by simply calculating the average scores of group members for each of their eight systems conflicts on the outer ring of the Quantum Wheel, as well as calculating the average scores of group members for their relative use of the five conflict modes on the hub of the Quantum Wheel, which are used for addressing and resolving their identified organizational conflicts.

On this Quantum Wheel, there are four systems conflicts, marked by an H, which reveal what has frequently been affecting group members in a negative way: both culture and skills in the informal systems, strategy-structure in the formal systems, and processes that mostly take place inside the group (gradual process improvement).

These HIGH systems conflicts that take place within all three categories of informal systems, formal systems, and processes clearly suggests that this work group is facing quite an assortment of barriers to performance and satisfaction, which severely undermines what members can provide to their organization. In addition, the remaining systems conflicts (teams, reward systems, radical process, and learning process improvement) are occasionally interfering with performance and satisfaction, as designated by the M for medium in those outer circles. It is useful to note that there are no systems conflicts that are rarely affecting this group. Every systems conflict is negatively affecting members, either frequently or occasionally.

In the HUB of this Quantum Wheel, the results that are displayed on the TKI Conflict Model reveal that these group members are heavily relying on competing and accommodating for resolving their systems conflicts (shown by the H for HIGH for these two conflict modes), which means that members either get their own needs met…or they do their best to get the needs of other members in their group met. Yet there is little compromising (shown by the L for that conflict mode), whereby each person gets at least some of his needs met. Indeed, the collaborating mode isn’t being used much at all (note the grayed letter L for that mode), so members aren’t taking the necessary time to generate creative solutions to their various systems conflicts—which would help them get their most important needs met, while also helping the organization achieve long-term success.

As seen on the same TKI Conflict Model for this group, the avoiding mode is being used more often than compromising and collaborating (shown by the letter M for the avoiding mode), but still less than competing or accommodating. During the program of eight tracks, especially during the culture, skills, and team tracks, group members will find it useful to discuss how their informal systems might be discouraging them from discussing certain topics, even though they’re being negatively affected by those particular conflicts.

Interpreting an Organization’s KOCI Results:

AFTER the Eight Tracks

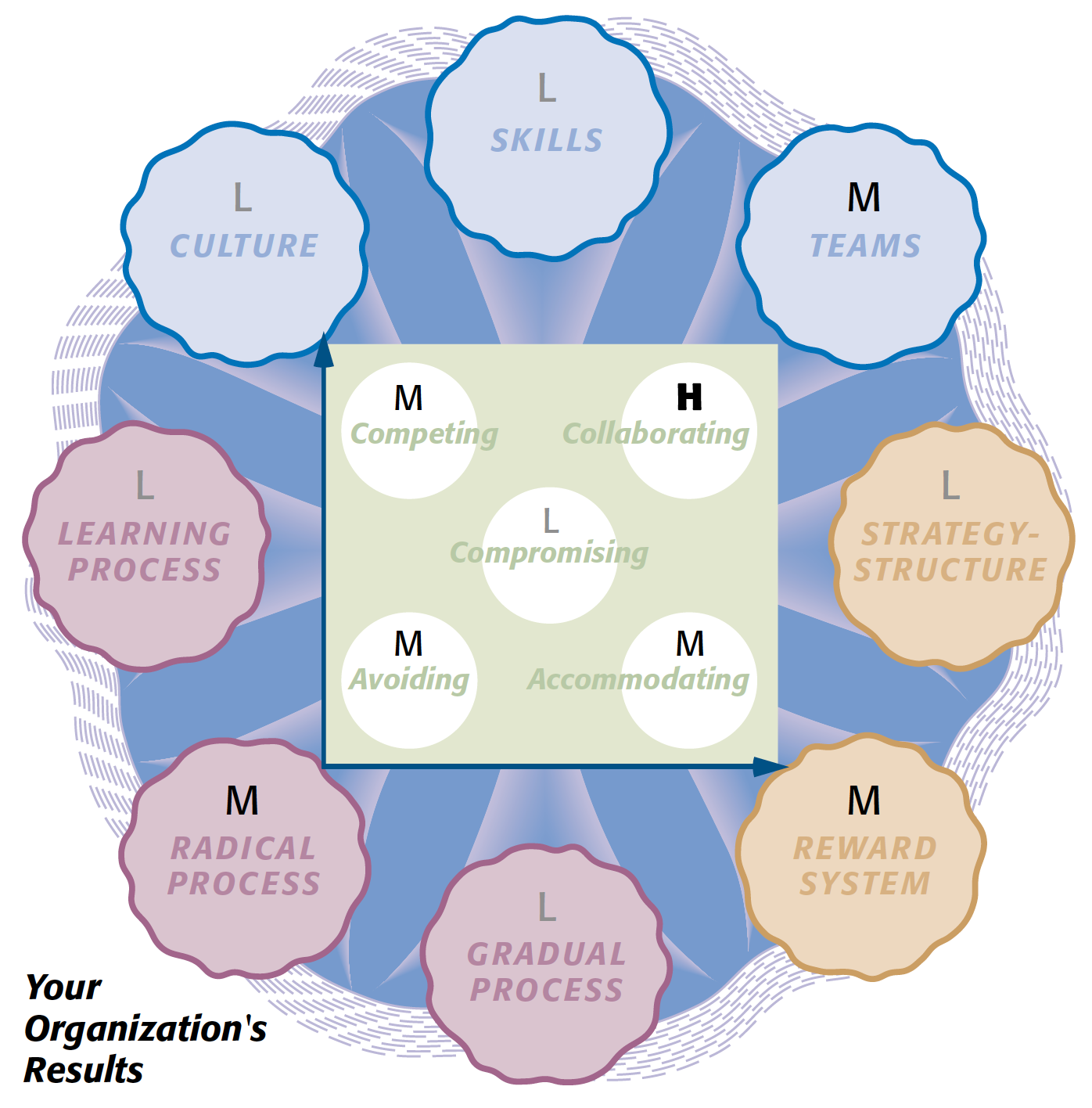

On the figure below is another graph of systems conflicts and conflict modes, but now we consider an entire organization, which is based on a simple average of all the members’ scores on their eight systems conflicts and their five conflict modes.

As you can see, none of the eight systems conflicts have been frequently affecting the members of this organization in a negative manner. Rather, five system conflicts are rarely being experienced negatively, if at all, which suggests that members can spend most of their time contributing all their wisdom and experience to the strategic mission of their organization—surely, an excellent outcome. Only three systems conflicts (teams, reward systems, and radical process improvement) are being occasionally experienced in a negative way, which reveals the few remaining organizational systems and processes that still need to be improved.

Based on the success of the first three tracks, there are predictable changes that have occurred on the TKI Conflict Model: The collaborating mode, displaying the bold letter H, is often used to resolve systems conflicts, which results in creative solutions that satisfy the needs of both internal and external stakeholders. Three of the other modes (competing, accommodating, avoiding) are being used moderately, displayed by the letter M, while organizational members are not making much use of the compromising mode. Perhaps in the spirit of openly discussing their systems conflicts in depth (due to the program of eight tracks), members might be missing opportunities to arrive at a middle-group solution when the issue is not that crucial for success, and thus more time should be spent on resolving their other, more important, organizational conflicts and business conflicts. As mentioned before, members tend to use some modes to the extreme, before they develop a more balanced use of all five conflict-handling modes.

THREE PRINCIPLES FOR RESOLVING SYSTEMS CONFLICTS IN ORGANIZATIONS

At this point, I’d like to remind you of the first key principle that derives from the Complex Hologram: About 80% of what takes place in an organization is determined by its systems and processes, while 20% is determined by member desires or preferences.

Now, I’ll add the second key principle to keep in mind, which follows directly from the first principle: Choose the particular conflict-handling mode that best matches the key attributes of the situation.

And here is the third key principle to remember at all times: In the short term, the organization’s systems and processes are fixed, so the use of one or more conflict modes might be significantly constrained by the nature and quality of the key attributes of the situation—which are largely determined by the organization’s systems and processes.

But in the long term, those systems and processes (which determine “the situation” for conflict resolution) can be transformed, which then changes the eight key attributes of any conflict situation to support the use of all five modes, as needed.

This third key principle reminds us that the collaborating mode—which is essential for resolving systems conflicts in a manner that satisfies the needs and concerns of all internal and external stakeholders—can only work successfully when the key attributes of the situation support using this mode, as in the case of stimulating (but not overwhelming) stress, high levels of trust among members, sufficient time to address the topic, and so forth. But if the current systems and processes do not support the collaborating mode (and, in fact, primarily support using the avoiding or compromising mode), then members, in the short term, won’t be able to use the collaborating mode to resolve their systems conflicts—nor will they be able to collaborate successfully on any of their other business, management, and technical problems.

In the long run, however, the organization can transform its systems and processes to support the use of the collaborating mode (as well as all the other conflict modes) to resolve not only any lingering organizational conflicts, but also to resolve any of their other complex conflicts and challenges.

CONCLUSIONS: USING THE KOCI FOR ORGANIZATIONAL CONFLICT

The figure below again shows the all-encompassing Quantum Wheel, which will hopefully inspire the organization to utilize all the wisdom, knowledge, talent, and experience of its members, no matter what the topic or focus of discussion happens to be.

For more information about the eight tracks and the critical success factors for implementing the tracks successfully, see my 2011 book, Quantum Organizations, which provides my most comprehensive and in-depth discussion of the eight tracks and quantum transformation.

You can also visit my website, www.kilmanndiagnostics.com, which includes many free articles, blogs, and videos, and where you can also purchase and take our sequence of 11 recorded online courses on conflict management, change management, expanding consciousness, and quantum transformation.

I wish you the very best in making use of the Kilmann Organizational Conflict Instrument in order to identify and then resolve the most troublesome systems conflicts that are getting in the way of all members being fully engaged—and empowered—in the workplace.