Is conflict bad?

Since some people have been hurt by conflict, they understandably want to stay away from it—or get rid of it. In fact, some believe the world would be a better place if there were no conflict at all. But once we accept that conflict itself is neutral, we can then see that its goodness or badness is entirely based on how it is handled. Indeed, any conflict can be addressed with respect and dignity or can be approached with anger and malice. But even more important, conflict can be a great opportunity to create better solutions to old problems. Not surprisingly, the TKI has been designed to promote the potential goodness of conflict—how it can be managed creatively—so it can help people satisfy their needs in all kinds of situations.

Is my approach to conflict deeply embedded in my personality or is it something I can easily change?

There is a well-known “equation” in the social sciences: Behavior is a function of personality traits and situational forces. Although personality traits are rather enduring properties of people and thus can’t be changed in the short run (for example, your psychological type, as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator), the TKI measures how you typically behave in conflict situations, not your enduring personality traits. Although your behavior may be habitual (automatically choosing to behave in a certain way, regardless of the situation), your behavior can also become very conscious and deliberate (carefully analyzing the situation beforehand, considering a range of behavioral options, and then matching your behavior to the situation). Indeed, once you take the TKI, calculate your scores, and profile your results, you’ll immediately become more aware of your behavioral habits in responding to conflict situations. And then, with the TKI’s interpretive materials, you’ll soon develop the ability to assess the key attributes of conflict situations, while knowing which mode best fits with a given situation. With practice, you’ll find it easy to choose behaviors—and quickly change them—depending on the attributes of the situation and what unfolds over time.

Why was the TKI designed with those A/B items?

Before the TKI was developed in the early 1970s, all the other conflict instruments were subject to a strong social desirability response bias: Respondents could easily tell which conflict mode, given how it was worded, had a positive halo (collaborating) and which one’s wording had a negative halo (avoiding). As might be expected, these undesirable halos significantly affected the self-report of conflict-handling behavior. But by pairing modes so each A/B combination is now equal in social desirability (as determined by several research studies), respondents can no longer choose the A or B choice according to which one makes them feel better about themselves (or seem more ideal to others). As a result, people taking the TKI must choose either the A or B item in each pair of statements by selecting the one that more accurately describes their behavior in conflict situations. Note: Even if responding to the A/B items seems cumbersome (probably because of their equal social desirability), your results on the TKI will be more accurate than would be the case if you took any other conflict instrument that hasn’t been carefully designed to minimize such response biases.

Why do items repeat on the instrument?

In real life, you’re always forced to choose which mode to use in a given situation—since you can’t use different conflict modes at the same time. To assess how often (relatively speaking) you typically choose one mode over another, we pair each mode three times with every other mode. Given all the possible combinations, that results in thirty TKI pairs in all. Sometimes the same item for a mode is used more than once, because it remains equal in social desirability with a different item for another mode. Other times, the wording of an item in a pair is modified slightly (or is rewritten completely) to ensure the social desirability of both items remain equal.

Why does the TKI consist of only thirty paired items? Don’t you need more items to accurately measure a person’s conflict-handling behavior?

The accuracy/reliability of any assessment increases rapidly as a second, third, and fourth item are added to the instrument. But after a while, adding more items only slightly increases the reliability of the instrument. In some cases, adding more items after a certain point actually decreases the accuracy of an instrument, because the additional items are adding other information, besides what the instrument is seeking to measure. At the same time, adding more and more items can annoy respondents, because they become tired of answering more questions—which can also distract from the accuracy of the assessment. With the results of several research studies, the total of thirty items on the TKI was shown to be a useful balance between (1) the reliability/accuracy of measuring the five modes and (2) people’s resistance to filling out a long assessment.

What is the reliability and validity of the TKI in comparison to other instruments that claim to measure the same five conflict-handling modes?

The first validity study for the TKI was published in 1977: Ralph H. Kilmann and K. W. Thomas, “Developing a Forced-Choice Measure of Conflict-Handling Behavior,” Educational and Psychological Measurement, Vol. 37, No. 2, pages 309-325. Regarding how the TKI compares to other conflict instruments, also see the 1978 article: Thomas, K. W., and R. H. Kilmann. “Comparison of Four Instruments Measuring Conflict Behavior.” Psychological Reports, Vol. 42, No. 3, pages 1139-1145. From just these early publications, the advantage of the TKI relative to other conflict-handling instruments (developed by Blake and Mouton, Lawrence and Lorsch, and Hall) is impressive—especially in terms of the TKI’s dramatic reduction in the social desirability response bias.

How can it be that people of different gender, race, age, and work experience all compare their scores to the same conflict-handling norms, as shown on the TKI Profile?

Prior to 2007, the TKI Profile was based on the mode scores of 339 middle and upper managers in business and government, who were primarily white males in the United States in the early 1970s. Since 2007, the TKI Profile is now based on a random, stratified sample of 8,000 respondents (drawn from a population of 59,000 respondents) who reflect the U.S. population on gender, race, age, work experience, and geographical location. See CPP’s report, The Technical Brief, for the full study. Remarkably, eight of the fifteen categories (high, medium, and low scores for each of the five modes) changed from the 1970s to the 2000s by only one number, while the other seven categories on the TKI Profile remained exactly the same. Even more striking, there were no significant differences, practically speaking, across any demographic distinction. That’s why everyone in the U.S. can use the one—recently updated—TKI Profile to discover the distribution of their five conflict modes into high 25%, middle 50%, and low 25%.

How can it be that people from different countries and cultures all compare their scores to the same conflict-handling norms, as shown on the TKI Profile?

In 2011, CPP provided its second report on TKI norms: International Technical Brief for the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument. This exploratory study included 6,168 individuals representing 16 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada (two samples—English speakers and Canadian French speakers), People’s Republic of China, France, Germany, India, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. All respondents, other than those who completed the Canadian French assessment, responded to a number of demographic items prior to taking the TKI assessment. These items pertained to organizational level, employment status, age, gender, years working in current occupation, and satisfaction with current occupation. Although the TKI international research sample of 6,168 respondents from these 16 countries was relatively small as compared to the U.S. sample (59,000 respondents, from which 8.000 were randomly selected), the international study suggested that, as a practical matter, the U.S. TKI norms (in particular, the high, medium, and low categories) do not diverge strongly from those of the countries in this study. Thus it is reasonable to conclude that the current TKI Profile can be used with confidence to interpret results for people of international origin and residence. In the near future, however, as more and more people respond to the TKI worldwide, cross-cultural studies will have a more solid basis (a large, stratified, random sample) for determining (1) whether the TKI Profile (based on the U.S. Norm Sample) needs to be modified to suit different countries or (2) if conflict-handling behavior is indeed so similar across countries and continents that what constitutes high, medium, and low scores on the TKI assessment, practically speaking, does not change much at all.

How can the TKI Profile show me as high on both collaborating and avoiding, when these modes are total opposites in terms of assertiveness and cooperativeness?

When the TKI Profile shows two of your modes as high, it merely suggests that you prefer to use them, probably too much, whenever your needs and concerns are incompatible with another person’s. But don’t try to read an unwarranted logic into these mode combinations, since their use has its own kind of logic. For example, if you come out as both high on collaborating and avoiding, your immediate response to a conflict might be to collaborate with the other person. But if he doesn’t reciprocate in a collaborative manner, your response might be: “I quit. I’m leaving.” Or you might first avoid the scene, unless the other person immediately asks to resolve your differences with a collaborative dialogue. Essentially, what makes being high on both collaborating and avoiding “logical” is simply that you have learned to approach conflict situations from one extreme to another. Indeed, any combination of two or more modes that are high (or low) has its own logic, because that’s the way you’ve learned to manage differences. Stated differently, your highest mode can be viewed as your most preferred mode; your next highest mode might be considered as your backup mode (just in case your preferred mode doesn’t work); and your lower modes are those you are not inclined to use, unless pressed to do so.

Is it harder to tone down your high conflict modes or boast up your low ones?

It’s probably easier to tone down your high modes, because you already know how to use them: You just have to use them less often and with more discernment. Regarding your low modes, however, your first response might be: “How—or why—would I ever use those modes?” This is often the case with the less assertive modes of avoiding and accommodating. Some people wonder why they would leave a situation or give in to someone else. But once they’ve had a chance to study the interpretive materials in the TKI booklet (see a SAMPLE REPORT), they’ll learn when avoiding or accommodating are the perfect choices for a given situation, and how their needs will best be met by using these alternative—unassertive—modes in the right place at the right time. But in such cases, it still might take some extra practice to use what beforehand was ineffectively viewed as either a “coward’s” or a “weakling’s” response to conflict. Similarly, if your low mode happens to be competing, you might first have to overcome the stereotype that “competing is aggressive and selfish,” before you can begin to use the competing mode more often—and more effectively.

Since the instructions to the TKI don’t specify a given situation, do my conflict-handling scores apply equally well to both my personal life and my work life?

The original instructions to the TKI are purposely general, so you can get an assessment of how you approach conflict across all kinds of situations. Some people, in fact, don’t vary their approach to managing differences, whether they are having conflicts with family members or fellow employees. But other people use very different conflict-handling modes in those two situations. To get a better reading on your behavior in these settings, you can respond to the TKI’s items in two different ways. Regarding your work life, use these instructions: “In work-related situations, we sometimes find our wishes differing from those of another person. How do you respond to such situations?” Regarding your family life, use these instructions: “In family-related situations, we sometimes find our wishes differing from those of another person. How do you respond to such situations?” Naturally, you can define other situations in the instructions—whenever you are interested in examining your conflict-handling behavior in a certain setting. Note: No matter how you change the instructions to the TKI, make sure you respond to every item with those specific instructions in mind.

The TKI interpretive materials say that each mode has its place, but I still want to know: What's the best approach for managing conflict?

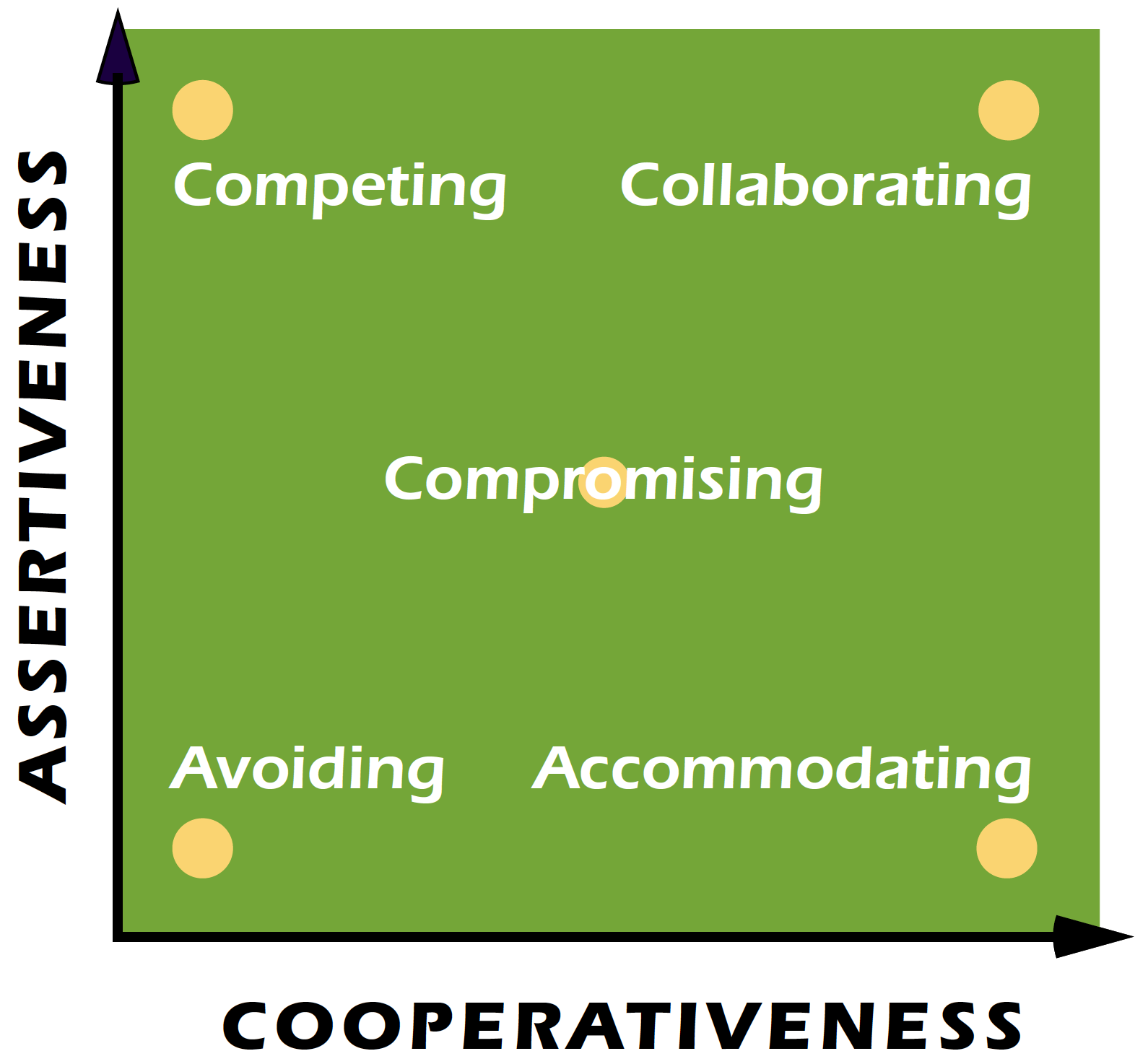

The best approach for managing conflict is a combination of these four lessons: (1) Know that you have five conflict-handling modes available to you at all times; (2) develop the ability to assess the key attributes of a situation (level of stress, complexity of issue, importance of issue, availability of time to address conflict, level of trust between both persons, quality of listening and communication skills, support from cultural norms and the reward system, and importance of the relationship to both people); (3) use the mode that best fits the situation; and (4) switch to a different mode as the attributes of the situation change.